|

|

|

|||||||

Going to Camp

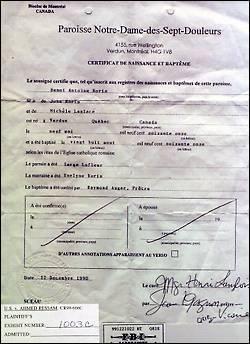

He began with a blank baptismal certificate stolen from a local Catholic parish. He found the name of a priest who was at the church in 1970 — his new year of birth — and forged the priest's signature on the certificate. And he created a new name, Benni Antoine Noris. That, along with a photograph, was all Ressam needed to get a Canadian passport. He didn't even have to take the forged certificate to the passport office himself, instead paying an acquaintance $300 to pick it up. Benni Noris, a Montreal native with a strangely Algerian accent, could now travel the world. On the evening of March 16, with Canadian intelligence agents eavesdropping, Ressam said goodbye to his roommates. One of the men even cried as Ressam left to board the bus to Toronto.

Using his new name, Ressam bought an airline ticket and flew from Toronto to Frankfurt, Germany. There, he met with al-Qaida contacts before flying on to Pakistan. He traveled by ground to Peshawar, perched at Afghanistan's rugged mountain border, where he met with Abu Zubaydah, the No. 3 man in al-Qaida.

Zubaydah gave Ressam traditional Afghani robes and assigned him a trunk in which to store his Western clothes. He told him to grow a beard so he would blend in with the Afghans. For the next three weeks, Ressam stayed at the Peshawar safe house, talking to other raw recruits, studying the Quran and praying. In late April, Zubaydah gave Ressam an introductory letter and sent him by car over the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan. From there, Ressam and other recruits marched on foot down steep hills to the Khalden camp. Khalden was a compound of four tents and four stone buildings. Recruits, 100 or so at a time, were grouped by nationality. There were Arabs from Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Yemen and Algeria, and Europeans from France, Germany, Sweden and Chechnya. Among the 30 or so Algerians were two of Ressam's former roommates from the Malicorne apartment, Sahid Atmani and Moustafa Labsi. Once the Algerians finished their training, they were to be supervised by Abu Doha, an Algerian living in London. By this time, al-Qaida training was formalized. There was even a textbook, available in Arabic, French and other languages. The training incorporated methods American advisers had introduced to the Afghans in the 1980s in the war with the Soviets.

Early each morning, Ressam and the others were called to formation, then sent to pray. After a meal, they went through strength and endurance training. Scarred veterans of the Afghan war taught self-defense and hand-to-hand combat, using knives, garrotes and other weapons.

As Ressam was being trained in terrorist attacks, other Islamists pulled off two to near-perfection: On Aug. 7, 1998, powerful truck bombs shattered U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, killing 224 people and injuring more than 5,000. The Clinton administration quickly concluded that al-Qaida was to blame. On Aug. 20, U.S. Navy boats in the Arabian and Red seas fired 70 cruise missiles at the training camps. Most missed their targets, and casualties were light. In Khalden, Ressam was unhurt. That summer, Doha, the Algerian ringleader, visited bin Laden at his base in Kandahar. Doha said he had a newly trained cell of Algerians, based in Montreal, that would be available to cross into the United States and wage jihad. By September, Ressam finished basic training and was sent to another camp, Darunta, for what amounted to terrorist graduate school. There, he took a six-week course in bomb construction. He copied into a notebook dozens of pages of notes and circuit diagrams and recipes for explosives. Before they left Afghanistan one by one, the Algerians discussed potential U.S. targets — an airport, an Israeli embassy, a military base. They decided the blast should coincide with the millennium. In mid-January 1999, Ressam left Afghanistan with his notebook, $12,000 in cash, and — unknown to him — a budding case of malaria. His assignment: Rent a safe house in Canada. Buy passports and weapons. Build a bomb to be used in the United States. On his way back to North America, he stopped in Peshawar to pick up his Western clothes and shave his beard. Based on his training about which airlines were lax in security, Ressam flew Asiana Airlines to Seoul, South Korea, then to Los Angeles International Airport, where he waited for a flight to Canada. It was the morning of Feb. 7, 1999. At a U.S. checkpoint, an agent stopped him and took his passport. In his bag, Ressam carried a notebook with bomb recipes. He also carried a shampoo bottle filled with glycol and a Tylenol bottle of hexamine tablets — two key ingredients for a bomb. The Immigration and Naturalization Service agent checked the name Benni Noris and the passport number against a computerized watch list. Although Canadian authorities had photographed Ressam leaving for an al-Qaida camp, the U.S. INS was clueless. Ressam was allowed to pass. He took his first look around America, the Great Satan. Families in Mickey Mouse garb. Men carrying golf clubs. Dark-suited women talking on cellphones.

Scouting the L.A. airport, one of the world's busiest, Ressam decided it was a perfect place to put his training into action.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Terrorist Within | Reprints seattletimes.com home |