|

|

|

|||||||

The Fountainhead

It was not something to die for. It was not something to kill for. Belkacem Ressam, Ahmed's father, prayed five times a day and attended services at the mosque on Friday nights. He did not demand that his five sons follow him, though.

Ahmed's mother, Benoir Malika, and his two sisters wore hidjab head scarves outside their home, but they did not wear veils to hide their faces. Inside the house, they wore pants, dresses and other Western clothes.

At that time, some beaches along the Mediterranean were posted with signs forbidding entrance to "dogs and Muslims." Europeans from France, Spain and Italy had long treated the Arab and Berber natives as churl, useful mainly for catching fish and shrimp along the Mediterranean coast or for harvesting the tomatoes, dates and olives that grew in fertile red coastal soil. Muslims were driven from their land, and many lived as what one prominent history calls "a ravaged people landless, homeless, jobless." The indignity became too much to bear, and in 1954, the teenaged Belkacem Ressam and thousands of his countrymen took up arms against the French.

The Islamic fighters, mujahadeen, were tenacious and ruthless. They used terrorist tactics — including bombing cafes and nightclubs — and dragged the French into a reactive trap of bloody reprisals against the general population. That in turn drew fence-sitting Algerians into the uprising against their European occupiers.

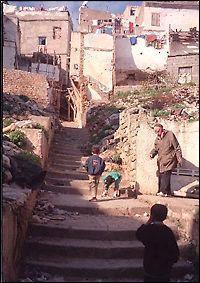

The cost of independence for Algeria was steep: hundreds of thousands dead. But hopes were high, and the new native leaders set up a welfare state that relied on its oil riches. Algeria would be a model for socialist development in Africa, with the words of Marx, not Muhammad, as guidance. As a war veteran, Belkacem Ressam could claim a place of honor in the new Algeria. A short, slender, soft-spoken man fluent in both French and Arabic, he secured a government job as a chauffeur. He settled his family here in Bou Ismail, a town of 40,000 that spreads from a narrow coastal plain up into pine-dotted hills. Their six-room house, its red-metal door engraved with a heart, was modest by Western standards but decent living in a nation where millions crammed into small, shabby apartments. Belkacem Ressam worked hard to put food on the table — rice, couscous, fruit, salads and, maybe a once a week, a dish with lamb or beef. He tried to leave the horrors of the war behind him and rarely spoke with his children about them. Instead, he looked forward with hope to the lives they would lead. He was especially hopeful for his firstborn: Ahmed, a shy, skinny boy with piercing hazel eyes and raven hair. Ahmed, born in 1967, was a lively child who liked to play soccer in pick-up games on neighborhood streets or catch small silver fish that could be grilled whole and devoured on the spot.

He was a decent student, and Belkacem Ressam planned that his son would take the tough qualifying examinations that would reward him with a free university education, modeled after the French lycee system.

But by his adolescence, Ahmed developed excruciating stomach pains. The Algerian doctors could not figure out what was wrong, and the teenager got worse and worse. Many nights, he tossed and turned in misery instead of sleeping. "He really suffered," a boyhood friend, Morad Cherani, recalls. "We found him all the time holding his stomach. We would ask him what's wrong, and he would say that his stomach ached." At 16, Ahmed was sent by his father to Paris for medical treatment. Perhaps the doctors there could figure out what was wrong. They did: a long-festering ulcer. The French doctors operated on him, and he remained in Paris alone, convalescing. When he returned home several months later, he had missed so many classes that he had to repeat a year of high school. He had a knack for numbers and was focused in the toughest track of studies, mathematics. But he failed his final exam. It was a stunning blow, denying him access to the university. Suddenly, life's options diminished. He tried to land a job as a policeman but was told he wasn't qualified. The doors to the middle class were closing in his face. He talked with his friends of returning to France. Or perhaps, he said dreamily, he would go even farther away, to a country in North America that was known as a friendly place for Algerians.

Along the walls of a street leading to the Ressams' home, someone spray-painted graffiti over and over, which said, simply, "Canada."

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Terrorist Within | Reprints seattletimes.com home |