|

|

|

|||||||

Leaving Home

In the mid-1980s, world oil prices collapsed, pulling Algeria's fragile economy down with them. As the nation foundered, its government rotted. Officials plundered what was left in the treasury. Millions of Algerians languished in poverty.

Meanwhile, in Bou Ismail and other villages, mosques were beset with recruiters who presented young men an opportunity: Come join the holy war, the jihad, against the Soviet invaders of our Islamic brothers in Afghanistan.

Thousands of Algerians answered the call, fighting in Afghanistan against Soviet troops, tanks and helicopters. Helped by millions of dollars in aid from the United States, Muslims from all over the world helped the Afghans hold onto their ancient land. When battle-hardened Algerians returned home, they were restless and ready to rid their country of its Soviet-inspired socialism. In 1988, mobs of angry young people rioted in the streets of the capital, Algiers. More than 500 of them were killed by the military. From the people's outrage sprang a powerful force: the Islamic Front for Salvation. Its leaders insisted Algeria be ruled by shariah, laws derived from strict interpretations of the Quran. Saudi Arabia had already embraced this fundamentalism — there it was called Wahhabism — as had Iran and Sudan. In a chaotic country, with millions of frustrated young men who couldn't find jobs, the militant Muslims found a receptive audience. "It was the language of the epoch — simple, demagogic and powerful," Omar Belhouchet, editor of the independent newspaper El Watan, remembers. Again, many young men answered the call. But Ahmed Ressam and his friends resisted.

Ressam, for one, had a job, albeit menial. His father had used his meager savings to open a small cafe.

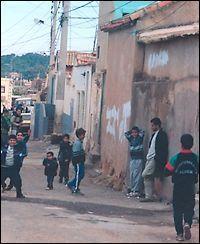

"We would say, 'Ahmed, bring us some lemonade,' " said Ali Rakeche, a teacher who frequented the cafe. "He was very timid and would not hurt a fly." From the cafe, it was only a dozen steps to the wood-carved doors of the town's largest mosque, Five times a day, loudspeakers on the twin minarets wailed with a call to prayer. As many as 3,000 could fit in the great room, kneeling on rugs, bowing east toward Mecca. Ahmed Ressam was not among them. Instead of donning white robes and skullcaps, he and his friends wore designer jeans and visited nightclubs. "Ahmed liked to dress himself well and go search for women. He had nothing to do with Islam," a family friend, Yousfi Boualem, recalls. "He was a handsome young man. He was cool and had no problem finding the jeune filles. Not women of the street, but nice young girls." Morad Cherani, one of Ressam's friends, says the group drank wine, smoked hashish and frequented Materez, a seaside nightclub with a swimming pool. Such activities were forbidden by the Quran and especially detested by Islamic Front members. Even the leader of the Bou Ismail mosque, Imam Mohammed Tazroot, was not observant enough for the militants. In June 1990, emboldened by Islamic Front victories in local elections across Algeria, militants took control of the mosque. They chased Tazroot out and threatened to kill him if he ever returned. "They banished me from the mosque and preached a religion of hate that had no connection to the true Islam," Tazroot says. "They said that anyone that did not follow them was against Allah." The militants started street patrols, looking for violations of their version of Islamic law. They wore Afghan turbans and white and green pantaloons, ringed their eyes with black makeup and carried cudgels.

They shut down stores that sold alcohol and cafes that allowed gambling. They knocked cigarettes from the hands of smokers. They stormed a classical-music conservatory — a symbol of the Western aesthetic — and smashed violins.

The military — still in control of the secular socialists — stepped in. They cancelled elections, declared a state of emergency and dissolved the Islamic Front. Some fundamentalists fled the country. But many — especially the mujahadeen who had fought in Afghanistan — remained. In August 1992, in a terrorist attack that resonated across the Islamist movement, they exploded a bomb in the Algiers airport, killing 11 and injuring 128. Government forces retaliated with detentions, executions and torture. Unpredictable violence was again woven into the texture of daily life. Algeria, briefly a beacon of hope in Africa, was about to metastasize into one of the world's most bleak and dangerous places. Belkacem Ressam, who had engaged in violence for the liberation of his country, agonized over what was happening to it now. He saw no parallels between his Maquis liberation fighters and what he viewed as thugs ravaging Algeria's streets and his generation's legacy. "These," he says, "were terrorists." His sons and their friends found themselves pressured to choose a side: the Algerian army, defending a failed and corrupt regime; or the Islamists, pushing an oppressive way of life. Ahmed, his father recalls, "wanted to get away from all this. He wanted to find liberty outside the country." Ahmed Ressam, eldest son of an Algerian war hero, made a decision. He awoke before daylight on Sept. 5, 1992, dressed, and said goodbye to his brother, Kamel. Kamel mumbled a few words of farewell from his bed.

Ahmed grabbed his bag, headed out the door and boarded a bus for Algiers, where he would catch a ferry for Marseille, France. In his pocket he carried a visa that would expire in 30 days.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Terrorist Within | Reprints seattletimes.com home |