|

|

|

|||||||

The Terrorist Tracker

Four men, wearing the blue uniform of Algeria's national airline, had charged onto an Air France jet on the tarmac in Algiers, killing two passengers. They wired dynamite inside the plane and were overheard discussing how to blow it up over Paris. The Algiers control tower refused to release the plane for takeoff and a tense standoff lasted two days. But after the hijackers executed a French passenger, threw him out onto the tarmac and threatened to kill another passenger every half hour, the Airbus jet was given clearance for takeoff to France. The plane touched down in Marseille, where the hijackers ordered it filled with 27 tons of jet fuel — far more than needed to make it the 400 miles to Paris. As the plane was being fueled, French commandos hid in mobile loading ramps rolled near the jet. In a flash, they stormed the jet, throwing in stun grenades. Through the smoke and noise, they shot and killed the four hijackers.

None of the remaining 177 passengers was seriously hurt. Massive tragedy had been averted.

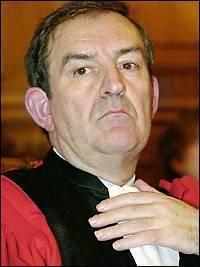

He was the world's most prominent terrorist tracker. He had investigated the French Action Directe, responsible for scores of bombings in the 1980s. He had pursued Palestinian terrorists in a 1982 grenade attack on a Jewish delicatessen in Paris. He had helped track down Carlos the Jackal, a high-living Venezuelan-born terrorist involved in attacks across Europe. As France's "terrorism magistrate," he headed a four-person team of judges responsible for investigating any terrorism that threatened the nation. The terrorists who commandeered Air France Flight 8969 were Algerians, members of the GIA, Groupement Islamique Armé, the Armed Islamic Group. They were fundamentalists who had been waging a guerrilla war against the military that ruled their homeland and were angered by French support of the government. They were closely associated with other Islamic terror groups. Bruguière knew the GIA had big ambitions. An investigation of the organization had yielded a drawing of the Eiffel Tower exploding. Had these hijackers intended to crash the fuel-heavy jet into France's icon? The previous year, Islamic terrorists had bombed the underground supports of the World Trade Center, trying to topple one of the twin towers. Were they targeting the architectural wonders of the West? And did this mean the terrorists, who had previously seen commercial airliners as tools of coercion or targets of bombings, were now seeing the potential of the fully fueled jets as massive, flying bombs?

Bruguière thought so. He traced these developments to what he saw as a "global Islamic menace": a network of terrorist groups working together on a worldwide scale.

They were indoctrinating recruits in terrorist tactics in the name of extreme Islamic fundamentalism. And, unlike earlier terrorist incidents tied to specific regional disputes, they were casting the world as a battlefield, believers vs. infidels. Bruguière's concern about the "global menace" deepened over the next year as more terrorist violence ensued: The torching of a U.S. embassy building in Algiers. A car bombing in the Saudi capital, Riyadh. A subway bomb attack that killed eight and wounded 84 in Paris. Meanwhile, a bizarre group of bandits with links to the GIA was becoming more active. Based in Roubaix, France, they were mostly of Algerian descent but were led by a Frenchman named Christopher Caze. A 25-year-old former medical student who had been raised Catholic, Caze had traveled to Bosnia to work as a hospital medic — and had returned as a radical Islamist. He wore white robes and black hair to his shoulders. Caze's "Roubaix Gang" was robbing banks, armored cars and supermarkets, using machine guns and grenade launchers and hiding behind masks — a Gallic version of Bonnie and Clyde. But it had more than money in mind. At the end of March 1996, leaders of the Group of Seven industrialized nations, including French President Jacques Chirac, were to meet in Lille, near Roubaix. On March 28, Caze's group rigged a Peugeot with explosives and compressed gas and parked it three blocks from the meeting site. French police discovered and defused the bomb before it could disrupt the meeting, or worse. And they found the gang hiding in a Lille apartment building. Four of the terrorists were killed in the subsequent police raid, but Caze escaped. He was stopped the next day at a roadblock, and police gunned him down as he tried to ram his way through. In his pocket, they found a Sharp electronic organizer — a storehouse of his terrorist contacts. Bruguière was called in. He sifted through leads, gathering phone-call logs and ordering wiretaps. Among Caze's contacts was one Fateh Kamel, a young Algerian whom Caze had treated for wounds in Bosnia. Kamel was an Islamic terrorist with suspected links to al-Qaida. What caught Bruguière's attention most, however, was Kamel's new residence: Montreal, Canada. This, Bruguière says, suggested that "the structure of the organization — and the targets — had changed. The targets weren't just in France or Europe." Islamic terrorists were in North America. In fact, Kamel had moved to Montreal in 1988. Clean-shaven and handsome, he had married a Canadian, opened a small arts-and-crafts business, had a son. He had lots of friends in Montreal's Algerian-immigrant community.

Among them: a quiet, unassuming man named Ahmed Ressam.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Terrorist Within | Reprints seattletimes.com home |