|

|

|

|||||||

'A Bunch of Guys'

Agents for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) knew Ahmed Ressam had traveled to Afghanistan to train to become a terrorist.

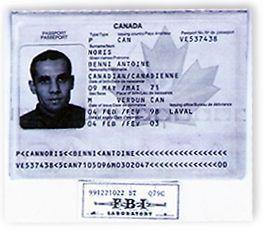

But when Ressam, posing as Benni Antoine Noris, came to the immigration window at Vancouver International Airport on Feb. 7, 1999, fresh from his Asiana Airlines flight from Pakistan by way of Los Angeles, he breezed right through. The ease with which Ressam re-entered Canada after attending terror-training camp illustrates why U.S. counterterrorism officials sometimes deride their neighbor to the north as "the aircraft carrier" — meaning terrorists can land and take off from there with impunity. Ressam spent his first month in Vancouver, B.C., then returned to Montreal in April. He expected four other Algerian members of his training cell to join him there, allowing him to return to the comfortable role of follower. But one by one, the others got stopped by authorities en route. He would have to step up. He began contacting other immigrants who said they, too, wanted to wage jihad.

His friends immediately noticed a change. Ressam seemed more confident. Eleven months before, he was just a thief. Now he was a fighter, a man willing to risk his freedom or his life for Allah.

But he soon heard troublesome news: His friend and mentor, Fateh Kamel, was in jail in France. Kamel had been tracked down by Jean-Louis Bruguière, the French terrorism magistrate. Bruguière found him in early 1999 in Jordan. The French judge persuaded Jordanian officials to arrest Kamel and extradite him on charges of abetting terrorism on French soil. Bruguière wasn't finished there. He wanted Kamel's Montreal cell mates, including Ressam, brought in by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and questioned on similar suspicions. In his April request, Bruguière insisted the other men could be charged with abetting terrorism because they had sent money orders and stolen passports to terrorists in France and elsewhere. But Canadian intelligence agents had seen little in their two years of surveillance to indicate that the "bunch of guys" in Montreal posed a serious danger, particularly not at home. Two months went by before David Gendron, a corporal with the Mounties' immigration-enforcement arm, was assigned to the case. Gendron visited the apartment on Place de la Malicorne, where Ressam and friends had lived earlier. But they had moved out. Gendron would have to track them down, if he could. Among the lessons Ressam had learned in the al-Qaida boot camps was how to avoid detection. He and his conspirators met at a doughnut shop or a Bosnian cafe, or conversed in a car. They used stolen cellphones and pay phones. And they moved a lot. Before he went to Afghanistan, Ressam's voice had been recorded in nearly 400 wiretapped conversations. Afterward, it was never picked up again by eavesdroppers. Bruguière was furious at the Canadians. He attributed their lack of urgency to a selfish sense of security, their belief that their nation's benign role in foreign affairs would immunize them against any attack by terrorists. What the Canadians didn't know was by 1999, Ressam and his associates were scheming against not only the Great Satan, the United States, but also against the country that had treated them so kindly. To pay for their plans, they needed cash, which they could get quickly only by stealing it. And when they didn't have enough cash, they would simply do what millions of North Americans do: Charge it. Through underground channels, Benni Noris, né Ahmed Ressam, had acquired a Royal Bank Visa card. For Ressam and his friends, there was something particularly sweet in using that ubiquitous tool of the corrupt and godless West to pay for the war against it.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Terrorist Within | Reprints seattletimes.com home |