|

|

|||

|

|

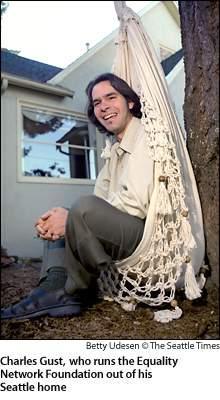

Learning the ropes Background, Related Info & Multimedia: Unlike those born into wealth, many of those who came into big money in the past few years didn't have a clue about how to deal with those questions. When Gust, who retired from Microsoft in 1998 after 10-plus years, first realized he could exercise his stock options, he was confused. He thought he would have to save money to "buy" the stock, not realizing he would actually make a profit exercising the options.

Hafer talks about being "outed" when a newspaper article first announced to the world that her family was rich. Each time new figures came out, "It was like being stripped naked. I felt incredibly exposed and almost ashamed. . . . It felt like a threat to my values, a threat to what I thought was important." Goldfarb, who says even their families don't know the financial details of their lives, insisted on using her childhood rather than current name for this article.

They learned how relationships can change overnight. And they wondered how in the world they could keep living the same "internal life," as Hafer puts it, with such wealth. When Hafer and her husband got the first million, gross, it was a shock. They had a barbecue, invited close friends and burned their mortgage. But the money didn't stop. "It was a frightening thing to have too much money. What do you do with it? Do you spend it on frivolity? Do you make sure that your children become trust-fund babies? How much do you hide?" For Hafer, part of the solution was to give away money and time. She now sits on the boards at Hopelink and the Center for Ethical Leadership. What to do with their family's money is clearly an "ethical challenge," says Hafer. "It's an incredible moral responsibility to have more than you need." Many of the newly wealthy had never defined career success in terms of money. Goldfarb calls herself a "nerdy musician," a saxophone player who became obsessed with "giving artists a way to truly speak though the computer." And her husband always thought of himself as one of the "wacky, creative people." So they cringe when they hear that phrase, now as familiar as "Boeing engineer": "Microsoft millionaire."

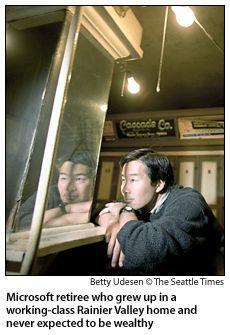

Even "philanthropist" sounds alien, says Gust, who set up the Equality Network Foundation with $1.4 million to work on justice and poverty issues. "It's a difficult word because for me, it brings up, you know, the Carnegies and the Kennedys. It brings up a whole other era and a whole other style." Money can also stealthily assume the role of other, more complex values, some newly wealthy people say. "Almost at a basic level, money is a proxy for other ways you think about your life," Hafer says. "There is this unexamined perception that money makes you a better person or a worse person – or a different person." Seattle has always had an ambivalent attitude about money. On one hand, it's been a frontier where many have come to seek their fortune, whether in gold, timber or software. "Striking it rich" was good, not a cause for anguish. But flaunting wealth has never been Seattle's style, compared with L.A., Houston or other fast-money meccas. Many of these newly wealthy live in homes that appear modest from the street and dress in Seattle mufti: jeans, natural fabrics and good-quality rain gear. Goldfarb's husband, Christopher, still can't say the word "wealthy" or "rich." He stops cold in the midst of sentences that lead there. He finds it ironic that he's being asked to talk about "wealth" – a word he never uses to define himself. They both use the word "embarrassed" a lot. As in Goldfarb's statement: "I don't want to live in a house I'm embarrassed for someone to come to." Embarrassed not by being too poor, but by being too rich. Money, for many, has meant the freedom to pursue dreams. Betsy Davis, who spent 14 years at Microsoft, starting work there in 1983 as a temporary typist, remembers asking herself: "What's my voice? What are my values? What do I believe in?" Now, she chairs the board of the Center for Wooden Boats, runs an eclectic shop in Fremont whose motto is "to enrich the soul, support the community, and protect the environment," and studies marine carpentry. Julie Edsforth, 34, returned to her dream of being a social worker after nearly four years at Microsoft, leaving before she was fully vested with stock options. She co-founded and directs, working part-time, a nonprofit that helps empower girls in public schools. Ikeda also left stock options on the table, despite his father's advice to gaman, a Japanese term meaning to stick it out. Wanting to spend more time with his family and to work in the community, he also helped found Densho', a project to preserve stories of the effects of World War II internment on Japanese-American communities. Now, he says he's "so lucky, so honored" to volunteer full time on the project, community boards and youth sports. Helping improve the world, he says, "is so much more fulfilling than when I was just focusing on my career. That's what money has allowed me to experience." The new money is opening doors for the community, as well. Hopelink, where the largest gifts were once $2,000 or $3,000, just received its third $1 million gift and successfully completed a $10 million capital campaign. But wealth can create challenges, as well. The "aggressive development" on the Eastside, Goldfarb complains, has led to look-alike houses and communities. When everybody's spending on the same things, she says "I think it can rob you of your independence." Similarly, trends such as home theaters can discourage people from mixing in the larger community, she believes. Having piles of money also can threaten relationships with friends and relatives. Goldfarb remembers her mother phoning her, upset, after she and her husband signed the deal to sell their company. "She said, 'I'm just worried that you're going to be different; you're going to be different from your brothers. They're not going to have what you're going to have, and I'm worried that you're going to change.' "Mom!" Goldfarb responded. "Did I ever steal any of the times I didn't have any money? No, I didn't steal."' Ikeda, a Franklin High School graduate, recalls a reunion of his junior-high-school classmates. He was dismayed to feel a distance. "They'd heard I'd been at Microsoft and made a lot of money, and they put me in a different space," Ikeda says. "People treat you differently. But inside, you don't feel differently." Children add another layer of complexity. Hafer moved her oldest child out of an Eastside public school because she found it too racially and economically homogenous."I don't want her growing up with the automatic assumptions that come from being a child of privilege." But her search for diversity came with a twist: She pays more than $10,000 a year to send her child to a private school, which recruits students from more varied backgrounds. Will Goldfarb's children believe the stories of how she and their father lived on bulk-buy frozen chicken patties for a year while struggling to keep their company afloat? "Creativity is born out of constraint," she says. "I was blessed with a tremendous hunger. I want my kids to have that." She knows she faces a challenge. On her bedside table, "The Golden Ghetto" book warns of the ways the rich can lose their children. Even their architect, Lane Williams, has grown deeply concerned about the trend toward megahomes and big, separate spaces, though many clients demand them. He knows, because he's seen it happen: You can lose your loved ones in 10,000 square feet.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [ seattletimes.com home ] [ Classified Ads | NWsource.com | Contact Us | Search Archive ] |