EVEN BEFORE we enter this house of mourning, we hear the women wailing. Sobs and shuddering sighs. Wrenching ululation. Somewhere, amidst the swish of skirts, a child's familiar hiccupy cry: Ruth's little boy, Tafadzwa. Hopefully his sister Martha is nearby to comfort him.

|

| BETTY UDESEN / THE SEATTLE TIMES |

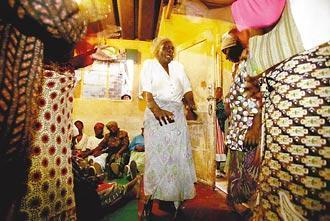

| For two days and two nights after Ruth’s death, women fill the tiny house to comfort her mother, Amai Caty, while the men huddle in silence outside. The vigil is, by custom, an unabashed display of grief, dance and song, all designed to usher Ruth’s spirit along. Almost everyone here has lost someone to AIDS. |

|

|

|

Outside, the clothes line stretches lonely across the yard, no laundry to cheer it. A red rag is nailed to the house to let passers-by know that the family grieves. Ruth's father, uncles and brothers huddle around a msasa wood fire, staring into the flames, sometimes choking as if something wants to get out, but mostly saying nothing, their mourning so quiet you can hear the fire hiss.

Inside, the rooms are cleared of furniture, the plywood boards that walled off Ruth's room taken down. Women fill the house: church ladies in blue headscarves, neighbors bustling around the courtyard kitchen, cousins pounding sadza with tall pestles.

Ruth's sisters collapse on each other, gripping so tight their fingernails turn white. Their mother slumps beneath a picture of Jesus. A photograph of Ruth and Richard hangs nearby.

Amai Caty flings her hands, palms and knuckles slapping the floor. These are the hands that washed her dying daughter. The skin is deeply lined, the fingernails slightly cracked, but there are no open wounds, no torn cuticles — no place, hopefully, for the virus to take hold.

Each new wave of mourners unleashes a new wave of sorrow that sweeps around the room. Many untuck small bills from the folds of their cotton overskirts and donate to Ruth's funeral expenses.

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

FACED WITH such suffering, what do you do?

We go to the market for cooking oil, firewood, tomatoes, onions, beef, chicken and four meters of white cloth for Ruth's burial garments and casket. The bolt of cotton leans askew on the shelf as if the general store does a brisk business in it. A week earlier, a meter of fabric cost 400 Zimbabwean dollars; this afternoon, in a country where the currency collapses daily, it's 590 Zimbabwean dollars, a tenth of Ruth's father's monthly salary. The total, for four meters, comes to $6 U.S.

The women cut and stitch the cloth for Ruth's shroud. Scalloped edges, diamond cutouts, the sign of a cross. A matching design to drape her coffin. A blouse, a cap and white panties for Ruth to wear next to her skin.