HAUDYE SWEET ne pepa raro. A popular Shona-language saying among men in Zimbabwe roughly translated: Having sex with a condom on is like eating a candy stuck in its wrapper.

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

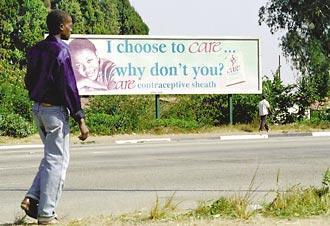

A CONDOM that's 98 percent effective doesn't work at all if it sits unused on a shelf.

|

| BETTY UDESEN / THE SEATTLE TIMES |

| Women have little control over sexual politics in the sub-Sahara, where men pay a lobola, or bride price, to marry them, and then set the rules. The traditional male condom has proved a weak weapon in the fight against AIDS, so global health workers promote women-controlled devices, such as the female condom touted on this billboard. |

|

|

|

PATH's design process relies on feedback from real people, using the products in real situations. On the back pages of a Seattle alternative weekly, the Stranger, alongside blurbs for amazing psychic astrologers, singles getaways and "Smoke Pot—Get Paid," a PATH ad reads: "Are you interested in women's health? Are you interested in developing the female condom?"

Couples in Seattle and around the world test prototypes, evaluating whether they are awkward to insert, uncomfortable, messy, puzzling, ugly, noisy or just right. A device is changed and sent out for more testing. The one-size-fits-most silicone diaphragm, now in clinical trials, went through 250 iterations.

Sexual practices can differ greatly from culture to culture. And internal anatomy can vary as much in size as a grapefruit and a kiwi depending on a woman's body mass, bone structure and how many times she's given birth.

In Mexico, women are "non-touchers," often unfamiliar with handling their genitals. In southern Africa, women regularly cleanse themselves with their fingers and sometimes use herbs and astringents to dry and tighten their vaginas. In Thailand, women suggested enhancing the appeal of condoms with feminine colors, flowers and perfume. "This product should be like Thai food," they told researchers. "Spicy, salty, hot and sweet."

"At the end of the day, people are having sex for all the wrong reasons."

— ANNA MANDIZHA, HEALTH ACTIVIST |

|

|

|

|

|

|

PATH's design team, led by Glenn Austin, translates feedback into improvements.

We want the product softer.

"Well, what does that mean?" Glenn says. "Is it too sharp? Should it be squishier? Bendier? Looser? Softer in the hand? To the man? Between the man and the woman?"

He sketches ideas in his black design notebook. On pages 13 and 14, he tackles the question: How to stuff the condom pouch into an inserter so it will neatly unfurl? IT'S INSERTION, STUPID! he writes in block letters. Pages of functional analysis follow, stuffing patterns that look like trumpets, pleats, Maypoles laced with ribbons. By page 17, the sketches resemble hibiscus blossoms.

"This is an ugly product, cost-driven and clinical," he says. "But it's also part of an intimate experience. So how can we make it beautiful? It's not going to be Chihuly, but can we make it neat, tidy, sexy, soft, easy to grab? How does nature achieve those shapes?"

Glenn is an avid gardener who once designed garden furniture and Gnu snowboard boots. That was fun, he says, but his work at PATH has meaning: "It's the ultimate to build something that you know is going to save lives."

Before going to Zimbabwe, before meeting Ruth, we ask Glenn if he imagines the lives he is trying to save. He says he doesn't envision couples making love in tropical heat or young wives managing the size of their families. Instead, he sees a landscape of orphans and old people: "Parents bedridden and dying, grandparents trying to care for them and for young kids, a wave of adolescents about to become sexually active."

Which brings us back to Zimbabwe.