WE STUMBLE from Ruth's house into blinking brightness, through the smoky courtyard, under laundry that drapes, no clothespins, over the line, back into the creaky green taxi that brought us here.

Our driver is Jesca Machingura, one of 10 female cabbies in the capital city of Harare. We'd met Jesca through Marvelous Muchenje, a manager at the Centre, a nonprofit agency that provides counseling and home-based training to families living with HIV and AIDS.

|

| BETTY UDESEN / THE SEATTLE TIMES |

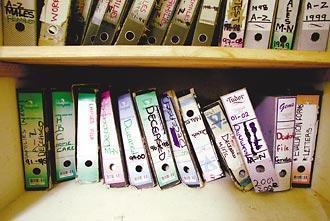

| AIDS remains so stigmatized in Zimbabwe that many donít seek treatment. At The Centre, a nonprofit HIV health and support agency in Harare, a shelf sags under the growing toll of AIDS reports. Clients are listed under "Worried Well" and Deceased. |

|

|

|

The Centre provides 2,000 patients with zinc, selenium, vitamins A and E. The Centre's garden grows aloe for herpes simplex, wormwood for diarrhea, fennel for appetite, rosemary for body warming, pennyroyal for thrush. There are only enough antiretroviral drugs for 35 people; patients number in the thousands. Inside, four shelves of patient records sag with thick binders. One is labeled "Worried Well." Eight are labeled DECEASED.

If we give money to the Centre, Marvelous says, she'll get gloves and bleach to Amai Caty.

We heard about the Centre, and thus Marvelous, through Lori Heise, who directs the Global Campaign for Microbicides, a worldwide advocacy effort headquartered at PATH's offices in Washington, D.C. Marvelous introduced us to Jesca the cab driver and to Prisca Nyakutombwa Mhlolo, a pushy community activist who coordinates women's support groups in Mabvuku township and who is, herself, HIV-positive. Prisca lives a few streets from Ruth's family and knows everybody's business. She introduced us to Ruth.

That's four degrees of separation. It feels like fewer as we settle into crocheted pillows in Prisca's living room.

We are women, so naturally the talk turns to food, family, money and love. We are women, so naturally no one agrees.

Jesca glances around Prisca's small but comfortable home. "This AIDS. If you're someone who has money, you can last longer."

Marvelous: "But I think you need love. You can have the money and the drugs, but if everyone is shunning you and no one cares for you, no one cooks for you, you won't have food to eat and you'll die."

Jesca: "Is that what the people around Ruth are doing? I don't think so. They love her and she's sick anyway! The problem is that that family doesn't have nutrition! Not enough meat! Not enough mealy-meal! What!what!what! No medicine! What if you've got love but there's no soup?!"

It's long past supper when we leave. We navigate the night, past empty vegetable stalls and glowing hooch stands, flickering grills where women hawk roasted meat and other favors, the lighted billiard hall where silhouetted men swig yeasty millet beer from fat plastic tubs. Music splashes from the bars: marimbas, mbira, the pulsing, socially aware lyrics of world-famous Oliver "Tuku" Mtukudzi. Tuku's brother died of AIDS.

We drive back into Harare along a modern highway lined with malls and an office complex for Nokia. In the era of cellphones, a Medieval plague.

Jesca talks nonstop while she drives. Her boyfriend of many years is a decent man, a schoolteacher, but he won't marry her. He puts her on his health insurance, calls her his wife, but what!what!what! he's never proposed. Never paid lobola! And why? Because he wants a woman who's humble and won't speak her mind, who only wears dresses and only wants to please him.

"I want to be free!" Jesca says. "Let me put on jeans and trousers and admire the person who I am. Most of the women who don't want to be oppressed have no husbands."

She shifts to the crux. She is HIV-positive, perhaps from an earlier marriage, perhaps from her boyfriend. He wants her to keep her status secret.

"If I don't disclose, how will other people know there's really AIDS? We must warn them. I'm not his wife! How can he tell me what to do?"

But she loves him. And he loves her. He brings her tasty fish from Lake Kariba. So why won't he marry her? Should she leave him while she's still strong and find someone more loyal?

"I wonder," she says, "when I'm sick as Ruth, would he run away from me?"

We are glad to finally reach our hotel. It's late, we haven't eaten since breakfast, we're anxious to call it a day. G'night Jesca! How easy to slam the taxi door on someone else's tangled life.

Only then do we remember: We forgot to give Marvelous money for the gloves.

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

WHAT IF you can help, but don't?

What if Ruth soils the sheets tonight?

What if Amai Caty has cuts on her hands?

Tomorrow. We will give Marvelous the glove money tomorrow.