Part 1: Dubious Deals

Mansions, cars, yachts, jewelry — then the bottom dropped out

/ Seattle Times staff reporter

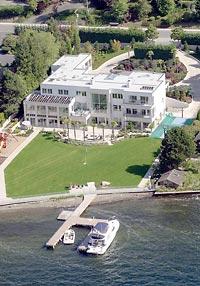

As InfoSpace's stock screamed skyward, software engineers in jalopies became Ferrari millionaires and company chief Naveen Jain found a stunning waterfront mansion only blocks from Bill Gates.

In spring 1999, Jain and his wife went on a house-shopping cruise around Lake Washington, docking at several multimillion-dollar mansions for sale. One home, owned by saxophonist Kenny G, had, among other touches, an automatic toilet-paper dispenser.

The Jains preferred something different and latched onto a 1.3-acre Medina estate called Diamanti — Greek for diamond — buying it for $13 million. The mansion boasted 16,500 square feet of space and a two-story garage. The garage shared a glass wall with the house so the owner could display an auto collection.

The house had a professional recording studio, steam room, sauna, exercise room, elevator and a two-bedroom wing for a housekeeper. The pool was covered with a two-story glass atrium so the Jains could swim year-round.

By then, Jain was worth $861 million — one of the 40 richest Americans under age 40, according to Fortune magazine.

Typically, high-tech startups had little money for salaries but enticed talented employees with stock options that someday might be worth a fortune. Jain gave his first InfoSpace employees lavish stock-options packages, 100,000 shares for a penny apiece.

As the Internet economy boomed, employees across the Puget Sound region sustained themselves on the dot-com dream that their startup would go public and their options would make them rich.

At InfoSpace, Jean-Remy Facq, a former Microsoft engineer born in France, worked for several months without a paycheck. He cashed in his Microsoft stock options to scrape by.

Kevin Marcus, who came to InfoSpace straight from college, slept on the office floor until he found an apartment and his future wife drove up from California. When they had a baby, they had to sell their car to pay the bills, and walked to work. To bring groceries home from the supermarket, they carted them in the baby's stroller.

Then, on the day InfoSpace went public in December 1998, Facq, Marcus and their colleagues became millionaires.

Like most of the instant millionaires, Facq and the others were not able to sell their stock for six months. But that didn't mean they couldn't start shopping.

![]()

A month after InfoSpace went public, Facq ordered a $103,000 Dodge Viper. He shipped the Viper to Hawaii, where he commissioned an artist to paint its hood with a Hawaiian scene — the sun setting over dolphins cavorting in blue waters. Tab for the paint job: $150,000.

But he got tired of waiting for the Viper, so on April 15, 1999, while walking by a BMW dealership, he went in and minutes later drove off in a Z3 convertible.

His friend Kevin Marcus and Facq started ribbing Charles Mathieu, a French engineer who also was an original InfoSpace employee, about driving to work in a Ford Escort. Mathieu soon bought a Porsche 911. Then Marcus bought a Ferrari for $675,000.

Not to be outdone, Facq two days later walked into a dealership and wrote a salesman a $1.1 million check to buy a Lamborghini Diablo and a Ferrari F50. "I just wanted to see the look on his face," Facq said.

Facq bought three kayaks and left them in his parking space in his condo's garage. This upset his condo association, which told him only cars could park there. So Facq bought a Subaru Outback and strapped the kayaks on top. In all, he topped out at nine cars. He made certain to drive each of his luxury cars past the Microsoft campus where his former colleagues worked.

Facq took out loans, using his stock as collateral. The higher the stock climbed, the more he could borrow.

One of the rings Jean-Remy Facq commissioned. |

His first creation featured a 4-carat diamond surrounded by gems representing the colors of the flags of France, his heritage, and Italy, his Ferrari's. He designed another to symbolize his software-debugging talents — a gold ring featuring a jeweled bug with a slash through it.

Facq even designed a "Founder's Ring" as a gift to Jain, a large ruby "planet" surrounded by a planetary ring of smaller rubies, a gaudy replica of the InfoSpace logo.

Before long, he added a 50-foot boat, 90-foot yacht, a condo in Whistler, B.C., and — for winters there — a mink coat.

Unable to find a home he liked on the water, Facq bought a $1.8 million house in Woodinville. Five months later, he found a $5.5 million house on Mercer Island. Its key attraction: The driveway was sloped gently enough so he could drive down it in his low-slung Ferrari.

Jean-Remy Facq sits in his $1.8 million Woodinville home. Suddenly deep in debt when InfoSpace stock collapsed, Facq had to sell it at a $600,000 loss. |

While he closed on his house, the stock collapsed. The investment banks, without enough collateral in the InfoSpace stock, called in Facq's loans. "My rocket stopped," he said.

He needed $8 million and borrowed it from Jain. As collateral, Jain took Facq's house on Mercer Island, his boat, his yacht and several rings.

Then the Internal Revenue Service told Facq he owed $5.5 million for the profit he had made on stock options, but by then the InfoSpace stock he owned was worth little.

Facq was able to keep his condominium in Kirkland and has gone back to work at Microsoft as a programmer.

"Since I lost everything, my life is simple," he says. "I don't have to wash the boat, I don't have to worry about the car batteries, I don't have to mow the lawn or worry about the gardener mowing the lawn. I'm happier now."

About this time, Jain discovered a problem with the large, expansive windows in Diamanti that afforded him such spectacular views. Unknown to him, the windows had been leaking for some time, Jain claimed, and now parts of walls had rotted and needed to be replaced.

Jain was furious with the previous owners. He accused them of not fully disclosing the problems, information he felt entitled to know before sinking his money into the mansion.

They offered to settle, but he rejected it. He would see them in court.

After a three-week trial in December 2002, the jurors found against Naveen Jain.

Copyright © 2005 The Seattle Times Company