As the '80s began, Advanced Technology Laboratories

introduced these first-generation scanheads to produce

real-time ultrasound images of soft tissue. Photo Credit: Advanced Technology Labs.

As the '80s began, Advanced Technology Laboratories

introduced these first-generation scanheads to produce

real-time ultrasound images of soft tissue. Photo Credit: Advanced Technology Labs.

BETWEEN 1979 AND 1983, WASHINGTON STATE'S ECONOMY SEEMED TO BE LOSING GROUND,

even as Boeing began recovering from the Bust. Pummeled by court decisions and

environmental legislation, the state's traditional industries of fishing and logging struggled

for survival, and unemployment in timber counties ran as high as 25 percent.

BUT A QUIET REVOLUTION WAS UNDER WAY IN AN OBSCURE SECTOR

known as "advanced technology."

Almost unnoticed, state high-tech employment increased 28 percent

during those tough four years.

In an industrial economy accustomed to lumber mills and copper smelters, high technology had

long meant Boeing's missiles, radar systems and jet aircraft. Otherwise, high tech happened

someplace else.

It was just as well, noted some locals, because technology was heartless.

Computerized robots would only force more workers to join out-of-work loggers and

fishermen. And what would they all do? Become computer programmers?

In 1980, The Times regarded high technology with considerable skepticism.

A year later, as the term "high tech" was entering standard newspaper usage, The Times noted

a number of small, local companies with promising futures. "Some may grow to become household words,

others may die on the vine," the story cautioned. This iffy group included Data I/O and Microsoft,

then boasting 100 employees and annual sales of only $15 million.

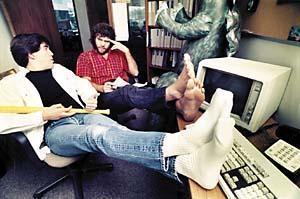

Hard at work, Kevin Scholfield and Andy Held reviewed computer code

in Microsoft's velvet sweatshop in 1989. Photo Credit: Tom Reese / Seattle Times.

Hard at work, Kevin Scholfield and Andy Held reviewed computer code

in Microsoft's velvet sweatshop in 1989. Photo Credit: Tom Reese / Seattle Times.

JUST DEFINING HIGH TECHNOLOGY PROVED "ABOUT AS EASY AS EATING

ICE CREAM WITH YOUR FINGERS," complained

one Times reporter. As late as 1983, Puget Sound's Economic Development Council

restricted the term to electronic equipment and computer manufacture. But exciting

local efforts in other kinds of high tech sprang from a new synergy between University

of Washington researchers and Boeing-trained engineering and management talent,

often laid off by the Big B.

The entire core group that founded Seattle Silicon, for instance,

had worked at Boeing until their program was discontinued; many of

the development engineers at Advanced Technology Laboratories and

Quantum Medical Systems had also come from Boeing. Gordon Kuenster,

guiding spirit of a succession of high-tech companies after his

departure from the Boeing B-1 program, remarked to a reporter

that Boeing was the area's largest source of high technologists in the early 1980s.

UW Professor Yongmin Kim demonstrated an imaging system that he and his students developed.

Photo Credit: Peter Liddell / Seattle Times, 1987.

UW Professor Yongmin Kim demonstrated an imaging system that he and his students developed.

Photo Credit: Peter Liddell / Seattle Times, 1987.

UW RESEARCH PROVIDED THE CORE CONCEPTS FOR A HOST OF LOCAL PRODUCT

DEVELOPMENTS in medical electronics and biomedical engineering. Worried about "the UW idea drain,"

the Washington Research Foundation was organized in 1981, joined two years later

by the Washington Technology Center, to foster and control the transfer of technology

from UW researchers to commercial development.

As the high-tech boom gained momentum in 1984, the development council published its first guidebook,

Advanced Technology in Washington State. In that Orwellian year, the guide found the top

five high-tech employers in the state, by workforce, to be Boeing Computer Services in Seattle,

Battelle in Richland, John Fluke in Everett, Keytronic in Spokane, and Tektronix in Vancouver.

Sundstrand Data Control, in Redmond, was the only Eastside firm among the top 10.

W. Hunter Simpson, a UW regent and president of Physio-Control,

lobbied for the Technology 21 initiative to attract more high-tech industry,

noting that "lifestyle, economic practicability, legislative compatibility and

educational strength" had made Puget Sound an attractive home for high-tech firms.

In 1988, Steven Gillis and Chris Henney stood behind the Immunex fermentation

tank used to manufacture recombinant proteins. Photo Credit: Tom Reese / Seattle Times.

BUT THERE WERE STUMBLING BLOCKS. The new entrepreneurs accused the state

of being unfriendly to high tech. Immunex CEO Stephen Duzan pointed out tartly

that his company would pay nearly $1 million in state sales and business-and-occupation

taxes before turning a dime of profit.

Others worried about stringent federal regulations and

the lack of local venture capital. But as the '80s wore on, high-tech growth

increasingly included local spinoffs and start-ups, as well as established firms

from outside the area.

Early in the 1980s, The Times measured these companies

by their number of employees and potential to diversify the state economy.

But at mid-decade, The Times grew fascinated with the science-fiction promise of

high-technology products, from genetic therapies to solar cells, defibrillators to operating

systems. The Times wrote breathlessly of start-ups, the grunge bands of 1980s' engineering

research and development, as "heady places to work," characterized by roller-coaster risks and

opportunities, keen camaraderie and a frantic pace.

Hot pursuit of the Next Great Thing by velvet-sweatshop

workaholics contradicted received management wisdom and flattened the corporate hierarchy.

Darlene Dorrough assembled the Heart Technology Rotoblator, a device for clearing arterial plaque.

Photo Credit: Pedro Perez / Seattle Times, 1992.

THE BRIGHTEST NEW IDEAS SEEMED TO BE COMING FROM SMALLER, NIMBLER SHOPS,

and investors scrambled to find the next Immunex, Aldus, or Advanced Technology Labs.

Newspaper readers learned of initial public offerings,

clinical trials, vaporware and stock splits, of wunderkind employees who worked not for

old-fashioned overtime but to earn stock options and retire at 30.

But of 10 start-ups, only one would bring a successful product

to market; and only one in 10 of those would develop a second success. The youthful

winners spoke of good science, good engineering, good luck and plenty of hard work.

1981. Microsoft publishes MS-DOS, the Disk Operating System that

would become standard on the majority of personal computers.

It started, Bill Gates wrote in "The Road Ahead," when, as a sophomore, "I stood in

Harvard Square with my friend Paul Allen and pored over the description of a kit computer

in Popular Electronics magazine." Here, Allen and Gates are at

Lakeside School in 1968. Photo Credit: Lakeside School.

HIGH TECH WAS SPINNING OFF NEW GENERATIONS OF START-UPS at

a faster clip, for higher stakes. The headstrong entrepreneurs who powered high tech in

the 1980s moved restlessly from job to job, looking for the perfect technical challenge,

the most exciting niche, the best chance to strike it rich.

By 1990, the Seattle metropolitan area was booming with industries perceived

as clean

and safe, developing products on the cutting edge of bioengineering, medical electronics

and computer software.

One of every 10 Washington workers was employed in a high-tech job,

and the sector was forecast to continue growing at an annual rate of more than 10 percent.

Washington state high tech roared into the 1990s, a major factor in the celebrated Puget

Sound livability as affluent, young, well-educated techies worked hard and played hard in

the silicon forest.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.