|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

November 2, 1996 Thousands of jets to be checked for jammed part within 10 days

By Byron Acohido

The inspections were ordered by the Federal Aviation Administration yesterday after the Seattle-based Boeing Co. acknowledged for the first time a 737 rudder-control problem that could imperil flights.

Boeing's twin-engine 737 is the most widely used passenger jet

in history. Yesterday's emergency directive covers all

U.S.-registered 737s. But since safety agencies in Europe and Asia

generally adopt FAA directives, the inspections likely will affect

more than 2,700 planes worldwide.

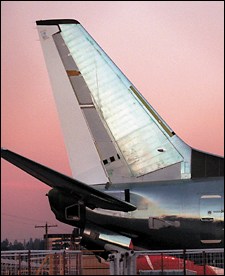

The emergency directive was issued after Boeing issued a service bulletin indicating its engineers had discovered a new way the 737's rudder-control system could inadvertently send the rudder all the way to one side. Federal investigators and a United Airlines mechanic earlier had discovered three other ways a 737 rudder could be inadvertently sent hard over. If a rudder hardover - an extreme movement of the hinged vertical piece of the tail section which control's a plane's left-to-right movement - occurs at low altitude and low enough speed, it is capable of snapping the plane into a dive that a pilot may not be able to correct.

The United jet was at 1,000 feet preparing to land at Colorado

Springs when it suddenly dove. The USAir jet was at 6,000 feet

approaching Pittsburgh when it twisted to earth.

"While the NTSB supports Boeing's efforts, we are doing a full analysis of this data to find out how it relates to the Pittsburgh and Colorado Spring's accidents," Hall added. "I am encouraged that this brings us closer to finding the answer to these twin tragedies." The NTSB on Oct. 16 approved more than a dozen safety recommendations to address apparent rudder-control problems on 737s. Those recommendations, which Boeing opposed, now go to the FAA. Boeing officials, who characterized the inspections as "routine," said the new rudder-control problem was discovered as Boeing engineers examined data gathered during an Oct. 11 rudder power-control unit (PCU) test at its laboratory near Boeing Field of one of the recently found ways a PCU could malfunction. Known as a "cold shock" test, it found that a PCU could jam when very hot hydraulic fluid was directed into a very cold PCU valve. The test had been initially conducted in late August, with similar results, at an independent laboratory in California. The test was designed to mimic conditions that might exist as a plane descended from very cold air at high altitude. However, data from the test showed the PCU valve could jam in a way that had nothing to do with temperature, said Jean McGrew, former chief 737 engineer. To test the finding, Boeing and Parker Bertea, the Irving, Calif., company that manufactures the 737's PCU, conducted a ground test on a Boeing 737 at Boeing Field Tuesday. McGrew said NTSB investigators were not present during the test. "The NTSB was not involved in that test because we were in a rush to find out where the truth was," McGrew told reporters yesterday. McGrew said the jet's PCU was rigged so the outer slide of its servo valve was jammed. When Jim McRoberts, Boeing chief test pilot, stomped on the pedal, the pedal sprung back and the rudder swung hard over in the opposite direction from McRoberts' command. In addition to a rudder reversal, McGrew said a jammed outer slide also could cause the rudder to deflect to an acute angle in the direction commanded. At a Thursday meeting of the NTSB's investigative group in Pittsburgh, Boeing representatives did not disclose the results of the Tuesday test or discuss the call for inspection Boeing was to issue yesterday. McRoberts said flight manuals contain instructions for how pilots can keep a rudder hardover from twisting and rolling a 737 into a fatal nose dive. However, McRoberts acknowledged that the plane would have to be flying fast enough for wing panels, called ailerons, to have enough power to counter the rudder and level the plane. One test conducted a year after the Pittsburgh crash discovered that the speed the USAir jet was flying when it flipped out of control was too slow for the ailerons to have any power to correct. The test revealed that Boeing's understanding of the air-speed control of ailerons was incorrect from the time the jet was certified by the FAA 30 years ago. Since the Colorado crash, investigators have discovered three other ways the PCU could produce uncommanded rudder hardovers, including contaminated hydraulic fluid, situations where one valve slide jams when the other already is stuck and when key valve parts are misaligned. The FAA in 1994 ordered upgrading of some valve parts in the belief that the change would prevent uncommanded rudder hardovers. But subsequent tests discovered the change merely eliminated one type of hardover. The emergency inspections ordered yesterday requires a trained mechanic or engineer to stomp on rudder pedals in the cockpit of all 737s and note how the pedals respond. If a jammed slide is detected, a properly working PCU must be installed before the plane is allowed to resume flying. Jets passing the inspections will have to be retested about every 30 days until a new part now being designed by Boeing can be installed. The inspections are "the nature of our business," said Charles R. Higgins, vice president of airplane safety and performance for the Boeing Commercial Airplane Group. "We identify very unlikely possibilities, and take steps to eliminate them, or at least to further reduce their likelihood of ever happening. That's one of the ways we keep enhancing the safety of the aviation system." Uncommanded rudder movements have plagued the 737 since it entered service in the late 1960s. Pilots have reported hundreds of flights disrupted in a manner suggesting inadvertent rudder movements. In addition to the unsolved crashes in Pittsburgh and Colorado Springs, rudder hardovers were suspected in 737 crashes in Panama in 1992 and India in 1994. Until now, Boeing has denied the 737 rudder-control system has problems and instead blamed reports of control problems on another part, called the yaw damper, which is designed to automatically move the rudder small amounts during flight to keep the jet flying a straight path. Because the rudder movements it commands are very small, Boeing has said it is incapable of causing a hardover. While denying that the 737's PCU was capable of causing uncommanded rudder hardovers, Boeing late last month announced that it was adding a device to new 737s. The device, called a limiter, would prohibit the rudder from moving more than a few degrees while the jet was flying above 1,000 feet. Boeing said the change was for technical reasons unrelated to the safety of the jet. Airlines with 737 fleets began preparing last night for the emergency inspections. Seattle-based Alaska Airlines, which has 33 Boeing 737s in its 75-aircraft fleet, planned to begin the tests late last night upon receiving the FAA's directive, said spokesman Lou Cancelmi. "Our philosophy is to do them as quickly and aggressively as we can," he said. "We think we can complete that within two days." He said the tests would be performed by Alaska Airlines maintenance personnel in Seattle, Anchorage, Portland and the San Francisco Bay Area. Phoenix-based America West, which has 10 flights daily through Seattle, planned to begin inspections late last night in Phoenix and Las Vegas, said spokesman Gus Whitcomb. America West has 61 Boeing 737s and expects to complete the tests "far ahead of the 10-day deadline." Of its 99 planes, 61 are 737s. A spokeswoman for Southwest Airlines, whose entire fleet of 241 aircraft are 737s, said the one-hour test of the rudder system "will be incorporated into our normal maintenance rotation" and will be performed by Southwest mechanics. The airline said it will adhere to the 10-day deadline. A United Airlines spokeswoman said the airline had not scheduled the tests. "We are working with the manufacturer to better understand the circumstances of the tests that led to the recommendation," said Connie Huff, a United spokeswoman based in Chicago.

Seattle Times staff reporters Leyla Kokmen, Michele Matassa Flores,

Christopher Solomon and Stanley Holmes contributed to this story.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company