|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

October 29, 1996

A debate over safety has embroiled Boeing's 737. Today, a look at discoveries about the 737's rudder-control system and at Boeing's pressure to blame the pilots after the Pittsburgh 737 crash two years ago.

At the controls of the 8-year-old Boeing 737-300 on Sept. 8, 1994, were Capt. Peter Germano and First Officer Charles Emmett III. Between them, they had logged more than 6,900 hours flying 737s. Their plane had been regularly serviced, including a maintenance check a month earlier during which its rudder system was inspected.

As the flight attendants prepared the passengers for arrival,

Germano and Emmett ran through the landing checklist and took

instructions from the control tower. Air-traffic controller Richard

Fuga instructed them to descend to 6,000 feet and slow to 190 knots

(218.5 mph). Germano complied.

"Sheez," said Germano. "Zuh," said Emmett. A series of unidentified sounds were then captured by the cockpit recorder. Thump. Clickety-click. Pssssssst. Thump. That's the moment investigators believe Flight 427's rudder moved suddenly to its extreme left - a movement known as a "hardover," which is not supposed to happen while a 737 is in the air - and locked in that position. In the next four seconds, the jet peeled off to the left, like a fighter plane in a World War II movie. Then it rolled upside down and began falling out of the darkening sky, nose pointed almost straight down. "Whoa," exclaimed Germano. Clickety click. "Hang on." The engines whined as the jet accelerated from 190 knots to 260 knots - nearly 300 miles per hour. Emmett grunted. "Hang on," Germano said again. A wailing horn warned that the autopilot had disconnected. "Hang on." "Oh (expletive)," exclaimed Emmett. "Hang on," Germano shouted. Some investigators believe that, at this point, Germano cranked his control wheel as hard as he could to the right, deploying wing ailerons in an attempt to counter the roll. When that proved fruitless, he exclaimed: "What the hell is this?" The control yoke began shaking, warning the pilots that the wings were about to lose all lift. An altitude warning tone sounded. With 12.9 seconds left, the following exchange took place: Germano: "What the . . ." Emmett: "Oh."' Germano: "Oh God, oh God." Emmett: "(expletive)." Germano: "Pull." The pilots yanked back on the control yoke in an attempt to raise the nose. Emmett: "Oh (expletive)." Germano: "Pull. Pull." Emmett: "God." Germano screamed. Emmett: "No."

Plummeting at 300 mph, Flight 427 sliced into a wooded ravine

and exploded in a huge fireball. In an instant, the gleaming, 50-ton

jetliner, carrying 132 people, shattered into hundreds of thousands

of smoldering pieces.

The crashes of 737s in Colorado Springs, Panama and New Delhi, and a near-crash in Honduras, had given experts from the National Transportation Safety Board and from Boeing a chance to increase their understanding of the ways a 737 rudder could misbehave. Many of these same investigators arrived in Pittsburgh the morning after the Sept. 8, 1994, crash. They were led by Tom Haueter and Greg Phillips, the safety board investigators who worked together on the 737 crashes in Panama and Colorado Springs. In the Pittsburgh crash, there was no reason to suspect weather as a factor. That left the pilots and the airplane. Each would undergo intense scrutiny. First would be the plane. Because eyewitness accounts, supported by radar data, depicted the jet twisting, then dropping straight down, a rudder hardover was immediately suspected. Records show Phillips made it clear right from the start that he would impose stricter evidence-handling rules than he had during the futile probe of the 1991 Colorado Springs crash. He directed the meticulous removal of the rudder's control mechanism (called a power-control unit, or PCU) from the wreckage, making sure its hydraulic lines were capped to preserve the general positioning of key parts, as well as its fluid. The PCU was stored for several days at a USAir hangar in Pittsburgh before being shipped to Boeing labs in Seattle. Because key parts had disappeared during the shipment of the PCU recovered from the Colorado Springs crash, Phillips insisted on chain-of-custody procedures documenting the handling of all the PCU parts. He even carried two small parts by hand to Seattle.

On Sept. 19, Phillips convened 20 investigators at Boeing's lab

in Seattle, safety board records show. Half of them were Boeing

engineers, and the rest represented Parker Bertea (the PCU's

manufacturer), USAir, the Federal Aviation Administration and the

Air Line Pilots Association.

Among the first things they found was that USAir had not yet upgraded the PCU servo valve's spring, spring guide and end cap on the ill-fated jet. Months earlier, in March, the FAA had ordered airlines to upgrade those parts to help prevent 737 rudders from reversing a routine command. USAir still had more than four years to meet the FAA's deadline. The improved parts were designed to ensure the spring, spring guide and end cap always stayed in precise alignment. Investigators found the USAir jet's parts, though not yet upgraded, were adjusted "within acceptable limits." The PCU then was shipped to Parker Bertea's lab in Irvine, Calif., where the investigators reconvened Sept. 21 for further analysis. This time all the parts showed up. The hydraulic fluid filters were removed and drained and the PCU hung upside down to drain the rest of the fluid from the main cavity. The bent piston rod was removed and the cavity examined. No signs of abnormal wear were found inside the PCU. A cover plate was then removed. Floating in the remaining hydraulic fluid and easily visible to the naked eye were small, shiny, metallic particles - flakes of aluminum-nickel-bronze, a material commonly used in bearings. Samples were taken, first with a syringe and then by pouring out the last of the contaminated fluid into a container. A fixed-up PCU passes test The investigators determined there was no way to test the PCU because all of the part's external levers, nuts and bolts were mangled. So, along with the bent piston, all the external parts were removed and replaced with new parts. The PCU was cleaned and injected with fresh hydraulic fluid. Only then was the unit tested. It functioned normally. Next, Boeing and Parker engineers ran a test to see if they could make the PCU reverse. They could not. On Sept. 23, two weeks after the crash, Phillips signed a report concluding the Irvine tests had "validated" that the PCU was "capable of performing its intended functions" and was "incapable of rudder reversal or movement."

Phillips' finding was a victory for Boeing. If it held up, it

could clear the airplane of responsibility for the crash and greatly

lessen or eliminate any financial liability for Boeing.

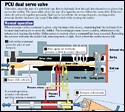

But Phillips would go a few steps further than he did following the crash in Colorado Springs, where evidence of dirty fluid was largely ignored. He asked hydraulic fluid maker Monsanto Corp. to measure the contamination level of the small amounts of hydraulic fluid recovered from the Pittsburgh jet. And he directed Boeing to account for the metallic particles recovered from the PCU cavity. Monsanto's measurements found the Pittsburgh jet's fluid to be 16 times more contaminated than hydraulic parts manufacturers recommend for aircraft systems. Boeing focused its attention on tests to determine if the metallic particles were important. Some investigators speculated that Flight 427's rudder could have swung hard over in response to a command from the yaw damper issued when the plane bumped into the wake of the 727. One way this could have occurred is if debris in the hydraulic fluid jammed the PCU servo valve's two internal slides just as the yaw damper was trying to make a quick rudder adjustment. See graphic at right. To address the question of whether the slides may have jammed, investigators relied on logic which Boeing's air-safety chief, John Purvis, had developed to rule out rudder reversal in a New Delhi 737 crash earlier that year. Engineers at Boeing's quality-assurance lab in Renton took a chip of high-strength steel and positioned it partially inside a tiny opening in the wall of one of the slides. The chip, indeed, caused one slide to jam against the other, one of the conditions necessary for a reversal, but in doing so it etched a mark on the slide surface.

Since no similar marks were found in the Pittsburgh jet's servo

valve, Boeing concluded, as it did in New Delhi, that dirty

hydraulic fluid could not have caused the rudder to swing all the

way to one side.

The NTSB's Phillips accepted Boeing's rationale despite a hydraulics industry axiom that jams tend to come and go, varying in severity and most often leaving no trace in the PCU. Numerous studies show, for instance, that when debris jams a hydraulic valve, then breaks free, the valve is restored to perfect working order, said Leonard Bensch, corporate vice president of Pall Corp., a manufacturer of hydraulic-system filters. "When the (debris) goes away, the valve works like brand new; put the (debris) back in and it doesn't work again," said Bensch, who is also an engineer. Boeing conducted another test to discount the possibility that dirty hydraulic fluid was a factor in the Pittsburgh crash. John Carulla, a Boeing engineer, took a PCU like the one used on Flight 427 and set it up so that a powerful hydraulic actuator constantly pumped the slides back and forth. This created a vigorous flushing action, something that would never occur in flight. Carulla then continuously added debris to the fluid until it was several times dirtier than the samples taken from the Pittsburgh jet. Although the hydraulic-fluid pumps failed several times and had to be replaced during the test, the PCU servo valve's slides never jammed. Referring to Boeing's tests, Phillips, the safety board's top rudder expert, said in an August 1995 interview: "I honestly believe that we've proven that contamination wasn't a factor." Safety measures are drafted Despite his public statements indicating a lack of evidence of any specific rudder-control problem having caused the Pittsburgh crash, Phillips remained concerned. In March 1995, Phillips drafted a detailed list of proposed 737 rudder-related safety measures. Phillips called for pilots to be alerted to the possibility of rudder hardovers and trained in special recovery maneuvers. He advocated redesigning the 737 rudder to drastically limit its range of movement during most phases of flight. Phillips' proposals became the focus of heated debate between Boeing and the NTSB for the next 19 months. Phillips' list eventually grew to include mandatory, periodic hydraulic fluid sampling and a limit on the number of flights a PCU could be used before it had to be replaced or overhauled. He also suggested far-reaching improvements for the yaw damper and called for fitting all 737 cockpits with an instrument that would tell pilots the position of the rudder at all times.

Meanwhile, Boeing had begun a campaign to blame the Pittsburgh accident on pilots Germano and Emmett. At a March 1995 NTSB meeting in Washington, D.C., Boeing presented a thick packet of documents loosely linking cases of pilot error over several decades to the Pittsburgh crash. The material included excerpts from dozens of psychological case studies about why pilots make mistakes. At Boeing's request, the safety board created a special "human performance" committee to focus on the possibility that Germano or Emmett caused the crash. The committee was chaired by Dr. Malcolm Brenner, the National Transportation Safety Board's psychologist, and included a Boeing test pilot, Michael Carriker; a Boeing psychologist, Dr. Curtis Graeber; three USAir pilots and two representatives from the FAA. In a series of meetings over several months, a debate unfolded as Carriker and Graeber made the case that one of the pilots must have stepped on the left rudder pedal and kept it depressed until it was too late to recover. Graeber cited the case of a helicopter pilot who occasionally made the mistake of depressing his left foot pedal, instead the right pedal, to turn right. Graeber said that was because, under stress, the pilot reverted to a familiar childhood memory: snow sledding. As a boy, he had steered his favorite snow sled by pushing his left leg forward to veer to the right. Perhaps, Graeber argued, one of the USAir pilots made a similar mistake while trying to adjust for what should have been a routine encounter with wingtip turbulence from a jet flying well ahead. Carriker and Graeber also suggested that one of the pilots may have depressed the rudder pedal as the result of a seizure, pointing to a 1980 incident involving a Frontier Airlines 737. In that instance, a co-pilot suffered a seizure, shoved the rudder pedal to the floor and nearly caused the plane to crash during landing. NTSB won't release paper The USAir pilots vehemently disputed Boeing's assertions. In late January 1996, Carriker and Graeber distributed a 25-page position paper to the other panel members laying out Boeing's argument for why the airplane couldn't be blamed and why the pilots probably caused the Pittsburgh crash. "They tried to attach it to the human factors group's factual report, but everybody raised so much hell, they withdrew it. It was so outrageous," said a source close to the special panel. A week after distributing the report, Boeing asked the panel members to return or destroy all copies, sources said. The safety board denied a Seattle Times Freedom of Information Act request for that document on grounds it was preliminary, deliberative material not required to be released publicly. Not surprisingly, word that Boeing was trying to persuade the NTSB to blame the crew did not sit well with many pilots. And it infuriated Chris Germano, the widow of Flight 427's pilot. "My husband was a very careful, very meticulous pilot. He paid a lot of attention to his skills and he was physically ready to do his job," she said. "I have to deal with the fact that my husband's trust was violated. He walked on that airplane knowing that he was capable of doing his job and his plane wasn't up to it." The NTSB committee so far has issued no finding on the role of the pilots.

With Boeing trying to blame the pilots and Phillips pushing to make 737s safer, two attorneys representing families of some Colorado Springs crash victims produced testimony that increased concern about the jets' rudder-control system. The testimony came in depositions of Steve Weik and Shihyung Sheng, two of the Parker Bertea engineers involved in the investigations of the Colorado Springs and Pittsburgh crashes. Weik and Sheng each unequivocally confirmed that any command to move the rudder slightly could result in a hardover in the direction commanded if both the PCU servo valve's primary and secondary slides happened to jam simultaneously. Weik testified that this design characteristic was known "from day one" by both Boeing, which designed the PCU, and Parker Bertea, which built it. Hydraulics experts consider such a dual jam to be highly unlikely. Nevertheless, Weik's and Sheng's disclosure meant an inadvertent rudder hardover theoretically was possible anytime a pilot depressed a rudder pedal or the yaw damper issued a signal to adjust the rudder - a command issued almost moment-to-moment on an average flight. It also meant that a servo valve modified according to the FAA's upgrade order to prevent rudder reversals could still be dangerous. A properly adjusted spring, spring guide and end cap could prevent a rudder reversal - but could do nothing to stop hardovers in the direction commanded, caused by a dual jam. See graphic on previous page. Boeing says jams 'improbable' In May 1995, the FAA completed a seven-month special review of the 737's control system and underscored the concern over dual-jam hardovers. The FAA's study pointed out that since the outer slide is rarely asked to move, it theoretically could jam - and remain stuck for some time - without pilots or mechanics noticing. Under that circumstance, the 737 would be a single failure away from disaster: If the inner slide jammed with the secondary slide already stuck, the result would be a sustained rudder hardover. The FAA asked Boeing to assess the probability of such a thing happening in flight. Boeing produced not one but three reports, which the company submitted to the FAA sometime before August 1996. According to Tom McSweeny, the FAA director of aircraft certification, the Boeing reports reconfirm what the company has asserted all along: that most rudder problems are controllable by the pilot and that rudder hardovers are "extremely improbable." However, McSweeny refused a Seattle Times request for a copy of Boeing's reports, saying they contained proprietary business information. McSweeny also said "the fact of the matter is, the average public isn't able to understand" the material. "That's why the FAA was created," he said, "to step in and do something."

"We have completed our review," McSweeny said. "And we concur

with (Boeing's) analysis."

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company