Originally published December 1, 2012 at 8:02 PM | Page modified December 4, 2012 at 2:39 PM

Elephants are dying out in America's zoos

Zoos' efforts to preserve and propagate elephants have largely failed, both in Seattle and nationally. The infant-mortality rate for elephants in zoos is almost triple the rate in the wild.

Seattle Times staff reporter

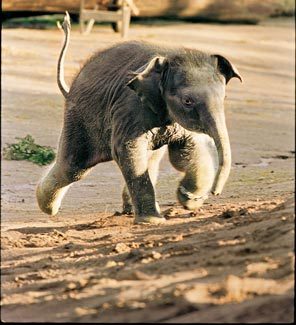

BENJAMIN BENSCHNEIDER / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Hansa, who in 2000 became the only elephant born at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo, plays with her mom, Chai, in October 2001. Hansa died at 6½ years old, the victim of a virus that had been killing young elephants at U.S. zoos.

STEVE RINGMAN / STEVE RINGMAN

112 ARTIFICIAL-INSEMINATION ATTEMPTS: Dr. Dennis Schmitt, center, visiting from Springfield, Mo., watches on a monitor as he guides a tube inside the reproductive tract of Chai as his assistant Cody Dalton injects sperm from a donor elephant last year. Elephant keeper Peter McLane is at left. A total of 112 artificial-insemination attempts have been made to impregnate Chai, now 33.

STEVE RINGMAN / THE SEATTLE TIMES

DAILY RITUAL: Elephants get their feet cleaned daily at Woodland Park Zoo. Foot problems exacerbated by standing on hard surfaces are a common ailment of zoo elephants.

GLAMOUR BEASTS:

The dark side of elephant captivity

Stories

Portland zoo updates

Related

Interactive: Thonglaw's tragic family tree

CLICK TO SEE GRAPHIC

Following long-abandoned practice, the Oregon Zoo mated Thonglaw with his daughters and Thonglaw's son Packy to his sisters, risking damaged offspring. Of the 22 offspring of Thonglaw and Packy, six elephants are still alive.

![]()

First of two parts

As the 1960s dawned, few Americans had ever seen a baby elephant. It had been more than 40 years since an elephant had been born in North America, and then only at a circus — never in a zoo.

But in a ramshackle exhibit yard at Seattle's Woodland Park Zoo, in the summer of 1960, the extraordinary occurred: A 15,000-pound male, Thonglaw, mated with a much smaller female, Belle, and Belle became pregnant. Zookeepers didn't know that elephant gestation takes 22 months, though, and they missed the pregnancy altogether. Unaware, they transferred the pachyderm pair to a zoo in Portland, under a sharing agreement.

In April 1962, at the Portland zoo, Belle gave birth to a male named Packy, and an international sensation was ignited. Life magazine devoted an 11-page spread to the birth. The country got caught up in a Packy craze, with toys, clothes and books bearing the cute baby's image flying off the shelves.

The public seemed to feel a unique connection to elephants, gentle giants who exhibit many humanlike qualities. Elephants live in families, exhibit memory and possess surprising self-awareness, such as recognizing themselves in a mirror. They experience grief and love, pain and fear.

Little Packy was everybody's baby, and attendance at the Oregon Zoo soared as visitors from all over the world waited in half-mile-long lines to see him. Cash receipts skyrocketed, and so did donations.

It was clear that elephants, the world's largest land mammals, were indeed "glamour beasts," box-office stars that would help America's zoos through the 20th century and into the 21st. Across the country, the race to produce baby elephants was on.

The effort would be good not only for zoos, officials insisted, it would be good for the Asian and African species that were under enormous pressure in their natural habitats. Zoos would help preserve and propagate elephants, they explained.

Fifty years later, The Seattle Times set out to examine how that effort has turned out. Despite the zoo industry's insistence otherwise, by almost any measure, it has failed.

A gamble goes bad

It took decades, but Seattle finally got its own baby elephant. In 2000, an Asian female named Hansa was born at Woodland Park Zoo, instantly bewitching the public. But 6 ½ years later, when she was found dead on the elephant-barn floor early one morning, zoo officials knew their gamble had failed.

They suspected an elephant herpes virus known as EEHV that had begun ravaging young elephants at a handful of U.S. zoos. The virus, believed to spread by contact, could lie dormant for years, then move so swiftly it could destroy internal organs in hours.

They knew that the virus had infected elephants inside the Springfield, Mo., zoo where they sent Hansa's mother to be bred. They feared it might find its way back to Seattle but the pluses "outweighed the negatives," they said, and they took a risk.

Besides, the zoo industry's governing body, the national Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), had privately approved Seattle's plan. The AZA was desperate to produce elephants, hoping to reverse or at least slow an alarming decline in the number of the animals in American zoos.

Publicly, the zoo industry was claiming — and continues to claim today — that "elephants are thriving inside zoos." It's a message that AZA officials have delivered repeatedly to lawmakers and regulators, trumpeted in news releases, and highlighted in a recent national marketing campaign.

But they know it's not true. And it never has been.

Rather, the decades-long effort by zoos to preserve and protect elephants is failing, exacerbated by substandard conditions and denial of mounting scientific evidence that most elephants do not thrive in captivity, The Seattle Times has found.

The overall infant-mortality rate for elephants in zoos is a staggering 40 percent — nearly triple the rate in the Asian or African wild.

Further, the same kind of virus that felled Hansa now has been found in a dozen zoos, as they circulated elephants around the country to try to breed much-desired offspring.

The Times did a first-of-its-kind analysis of 390 elephant fatalities at accredited U.S. zoos for the past 50 years. It found that most of the elephants died from injury or disease linked to conditions of their captivity, from chronic foot problems caused by standing on hard surfaces to musculoskeletal disorders from inactivity caused by being penned or chained for days and weeks at a time.

Of the 321 elephant deaths for which The Times had complete records, half were by age 23, more than a quarter of a century before their expected life spans of 50 to 60 years.

For every elephant born in a zoo, on average another two die. At that rate, the 288 elephants inside 78 U.S. zoos could be "demographically extinct" within the next 50 years because there'll be too few fertile females left to breed, according to zoo-industry research.

In the baby race set off by Packy's birth, zoos in the 1960s and 1970s recklessly bred father with daughter, brother with sister, practices since abandoned. The tainted bloodlines of these offspring still impair efforts to safely breed today.

Woodland Park and zoo-industry officials defend captivity as a tool for scientific advances that have benefited both captive and wild elephants. Additionally, they argue that live-animal exhibits are the best way to boost public awareness and raise funds for conservation efforts.

"We are trying to save elephants in zoos," said Bruce Bohmke, Woodland Park chief operations officer. "We'd never do anything to hurt our elephants," he said. "They are happy here."

Steve Feldman, AZA spokesman, said the association over time has raised standards that make life better for zoo elephants: more living space, softer indoor surfaces to reduce foot and joint stress, and limits on the use of chains and bullhooks, a long-handled, clawed-end training tool used to gouge, poke and strike elephants.

Feldman said many zookeepers think high death rates can be reversed with better-managed breeding programs. Other tactics include importing more elephants from the wild for genetic diversity, and using recent medical advances to fight the elephant virus.

"Our future looks brighter that our past indicates," Feldman said.

But some industry leaders say it's time to discard the traditional Victorian-era model of the menagerie: one of every animal.

"Elephants don't thrive in zoos," said David Hancocks, who was director of Woodland Park Zoo from 1976 to 1984. "We didn't understand elephants very well in the 1970s or '80s. But there is overwhelming scientific evidence today that shows the harmful impact of captivity."

Gifts of elephants

Woodland Park's efforts to breed elephants were unrelenting and emblematic of the quest by dozens of zoos to create their own glamour beasts at any cost. The story begins with Hancocks, a notable architect from Great Britain who arrived in 1975 to redesign Seattle's squalid, outdated zoo.

His pioneering designs featured natural habitats, known as the "immersion experience" for both the captive animals and visiting humans. Hancocks mesmerized city officials and was promoted to director of the zoo.

Hancocks began with the apes. He transformed the bleak, prisonlike ape pen into a lush, free-roaming micro-world. The design garnered national acclaim.

He next turned to the elephants and a dank and dimly lit two-room barn where zookeepers chained two female elephants — Bamboo, 14, and Watoto, 11 — for as long as 17 hours a day.

"Conditions were horrible," Hancocks recalled. "I planned to close the exhibit."

But those plans changed in 1980 when Thai Airways International, promoting a new overseas route, gave Seattle an unusual gift: a baby Asian elephant.

"What could I do?" Hancocks said. "The mayor, the public, everyone wanted this elephant. I couldn't refuse."

Attendance broke records at the city-owned zoo; hundreds of visitors circled the elephant exhibit daily.

The newcomer was named Chai — Thai for victory. She had been plucked from her mother at age 1 before being weaned, a common practice because zoos coveted crowd-pleasing calves. Chai was joined the following year by another 1-year-old Asian elephant, Sri — this time a gift from a Thai zoo.

The four elephants shared an 8- by-18-foot south room and a 20-by-42 north room. Conditions were so cramped that they were chained at night so they wouldn't accidentally roll over each other.

Hancocks said he was incensed by the substandard conditions — tight space and little activity for the elephants, particularly on cold days. Each elephant developed foot disease. He petitioned the Seattle City Council to build a new $3 million elephant exhibit. When city officials balked, he resigned.

The exit of the highly regarded Hancocks cast a national spotlight on Seattle's dilapidated zoo. In response, embarrassed city officials launched a "Save our Elephants" campaign, which pulled in millions of dollars in donations worldwide for a new world-class elephant house. When completed in 1989, it included larger, heated rooms, an outdoor yard adorned with trees, bushes, a wading pond and up-close viewing platforms for the public.

Seattle zoo officials decided it was time to increase the size of their herd. Blood tests showed that Chai had a predictable reproductive cycle and was the best for breeding.

An artificial solution

Zookeepers considered two pregnancy options.

They could cart Chai to another zoo and let the natural mating process take place. But such a trip would be costly and the zoo would lose Chai for nearly a year.

Or they could try artificial insemination. Though less expensive, it was experimental. No zoo at the time had successfully impregnated an elephant. Even so, Seattle zookeepers opted for artificial insemination.

Because it was an unnatural and invasive procedure, keepers had to train Chai to accept artificial insemination. First, they needed her to learn how to stand still for long periods without panicking. Zookeepers chained Chai's four legs to anchors, pulling them tight so she couldn't move an inch — a technique called "short chaining."

In the next phase, zookeepers got her used to having a long, flexible hose inserted into her winding, 3-foot-long reproductive tract. Zookeepers conducted mock inseminations on Chai for about two years.

In 1992, using elephant sperm shipped by Greyhound bus from the Oregon Zoo, zookeepers performed the first artificial insemination on Chai. They had recruited a staffer who had the "longest arms," records show. The sperm was pumped through the hose.

They repeated the procedures on Chai up to 10 times a month — sometimes twice a day, medical records show — with no success.

Still, zookeepers kept up hope. After a February 1994 insemination, one wrote on a medical log, "Come on sperm!"

After four years and 91 attempts at artificial insemination, Woodland Park Zoo officials grew weary of waiting for Chai to conceive. They petitioned the AZA to breed her at the Dickerson Park Zoo in Springfield, Mo. The AZA, founded in 1924, is funded by memberships and provides its seal of approval, or accreditation, to those that meet the standards the zoo industry sets for itself. To remain accredited, a zoo must get AZA approval for its breeding plans for elephants and other animals.

Some Woodland Park zookeepers worried about sending Chai to the Missouri zoo. Dickerson Park was among a handful of zoos nationally that had experienced a lethal outbreak of a mysterious virus that killed only young elephants.

The dormant virus, which may hitchhike on elephant skin, can inexplicably flare into an infection that can ravage internal organs in days, sometimes hours, eating away tissue so rapidly that by the time an infected elephant drops to the ground it may already be dead.

The virus — elephant endotheliotropic herpes virus (EEHV) — was first identified at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., in 1995, after the death of a 16-month-old calf.

Despite the dangers from the virus, or that Chai might carry the virus back to Seattle, an AZA breeding committee gave its approval.

"It was decided that the plusses (a baby elephant) outweighed the negatives," according to a May 1998 Woodland Park memo that detailed zookeeper concerns.

That fall, at a cost of $50,000, Chai was sedated and trucked more than 2,000 miles to Missouri.

Rough regimen

Dickerson Park Zoo, like Woodland Park at the time, was a "free contact" zoo. Keepers trained, fed and cared for animals without any barriers between them. To control and train elephants, keepers used restraints and bullhooks to mold behavior and establish who's in charge.

At Woodland, zookeepers characterized 8,600-pound Chai as shy and submissive, with no history of aggression. Within her first three days at Dickerson Park, keepers said, Chai turned dangerous and required restraints and physical punishment.

Two witnesses, upset by what they saw, said that Chai was chained by two legs and repeatedly struck with a bullhook during a two-hour training session in September 1998, according to a complaint from whistle-blowers filed with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which regulates zoos.

Woodland Park and Dickerson Park officials disputed the accusations. They asserted that Chai had knocked down a keeper and later lunged at him. Chai was slapped several times with a bullhook but the skin was not broken or bruised during a brief disciplinary session, zoo officials said.

Even so, USDA inspectors cited Dickerson Park with a violation of the Animal Welfare Act for causing "trauma, behavioral stress, physical harm and unnecessary discomfort." The zoo paid a $5,000 fine.

Chai had a hard time being accepted by the herd. Some elephants gouged and rammed her body. Keepers placed her in protective captivity after one elephant bit off a piece of her tail. Her weight and health rapidly deteriorated, medical records show. Zookeepers dosed Chai with Valium, an anti-anxiety narcotic, and azaperone, a tranquilizer, to calm her down and make her easier to handle.

Regularly, she was put in the same indoor paddock with Onyx, a prolific bull elephant.

When Chai was returned to Seattle, she weighed about 7,300 pounds — a loss of 1,300 pounds. But she returned pregnant.

Training by force

On Nov. 3, 2000, for the first time in Washington history, a baby elephant was born. Chai gave birth to a girl, weighing 235 pounds on wobbly feet, flourishing a 10-inch-long trunk.

Woodland Park had a naming contest for the baby elephant and from more than 27,000 entries, officials picked the winner, the suggestion of a Redmond schoolgirl — "Hansa," the Thai word for "supreme happiness."

Gate revenue and donations doubled at the Woodland Park Zoo, showing the economic power of a new glamour beast.

But baby elephants quickly lose their newborn cuteness and crowds taper after the first year, zoo studies show. By 2, Hansa weighed about 1,500 pounds and was undergoing training. Some Woodland Park visitors were aghast after hearing Hansa bellow and seeing a zookeeper strike her several times with a bullhook. Chai stormed out of the elephant barn to protect her daughter. The keeper later explained he was disciplining Hansa for eating dirt.

Officials defended the use of force, saying the blows did not harm Hansa. Later that year, Woodland Park switched to "protected contact" and dealt with its elephants mostly behind bars or barriers and discontinued using bullhooks.

As Hansa matured, zookeepers regularly conducted blood draws and hunted for evidence that she was infected with the herpes virus. It was appearing in more zoos and was a leading cause of death for captive Asian elephants under age 7.

Zookeepers resumed artificial insemination on Chai, hoping for another baby elephant.

The odds of success had gradually improved, enhanced by the use of ultrasound imaging that enabled precise placement of sperm. The rubber hose and air pump had been replaced by a 4-meter-long endoscope-equipped "artificial penis." And in lieu of chains, the zoo used a large steel-barred chute with contractible walls that could gently pin an elephant in place. It's officially known as an "elephant restraint device" or ERD, but zookeepers have nicknamed it the "iron maiden."

Import squeeze

By 2003, the weight of scientific evidence that elephants failed to thrive in zoos, combined with pressure from animal-welfare groups worldwide, prompted U.S. agencies to dramatically slow the importation of wild elephants. An easy supply of elephants masked the premature deaths and decline of captive elephants in U.S. zoos. With their supply line nearly closed, zoos stepped up captive breeding to replenish the dying ranks.

The zoo industry also faced another problem: The Detroit Zoo said it was giving away its elephants to a nonprofit sanctuary. Cold weather and captivity took too high a toll on its elephants, the zoo director said.

Then a cluster of unexpected deaths of zoo elephants unfolded over several months in Chicago, San Francisco and elsewhere. The deaths not only made national news but sparked protests from animal-welfare groups that "gain momentum every day of the week," a concerned AZA member wrote in an email.

The Association of Zoos and Aquariums decided to fight back. In January 2005, it organized a private two-day meeting at Florida's Walt Disney World with representatives from dozens of zoos that housed elephants. Among them were Woodland Park Zoo's chief executive Deborah Jensen and Bruce Bohmke, deputy director at the time.

All agreed the death toll of captive elephants had risen to "crisis levels." According to documents and reports reviewed at the meeting, neither the African nor Asian elephant population was sustainable under current conditions.

They agreed to "speak and act with a unified voice" in claiming that elephants were thriving in zoos. Together, they hired a crisis-management firm and agreed to dub critics of elephant captivity as "extremists." They also committed in writing to aggressively breed elephants, following a "species survival plan."

To that end, later in the year Chai underwent her 99th artificial-insemination attempt. And Woodland Park officials won approval to breed Sri, then 12, at the St. Louis Zoo.

Sri quickly became pregnant. But near the end of her term, the calf in Sri's womb died. She still carries the mummified, stillborn calf.

For now, Sri remains in St. Louis, officially on loan, but is never expected to return.

Sudden death

For six years, Hansa showed no signs of medical problems.

In June 2007, she exhibited mild symptoms of colic, a common and treatable digestive disorder. She showed signs of improvement.

During the night shift on June 7, a watchman reported nothing unusual and went home at midnight. The next morning, before public gates swung open, Hansa was found dead on a rubber-matted concrete floor.

A necropsy revealed the cause of death: a strain of the elephant herpes virus.

Hansa was cremated. Mourners left flowers and stuffed animals in a makeshift memorial outside the zoo's south entrance

The strain that killed Hansa was a new variation. So which, if any, elephant was the carrier?

Tests showed that none of Woodland's three elephants was infected. But researchers have yet to develop a test to detect the virus in its dormant stage, so it remains unknown if any of the elephants were carriers.

An emerging theory is that the dormant virus may already reside in the bodies of elephants; when it turns active, it can spread by contact or be passed from mother to calf during pregnancy.

But some animal-welfare groups, relying on zoo records to track the path of the virus, believe that the zoo industry's practice of transferring elephants around the country to breed has contributed to the spread of the virus. Dickerson Park was one of the nation's hot spots for the elephant virus at the time Hansa's mother, Chai, was sent there in 1998. Indeed, six months after Hansa's death, the virus claimed a 2-year-old Asian elephant living at Dickerson.

112 artificial attempts

Like Woodland Park, many other zoos have pinned their hopes for crowd-pleasing new elephants on artificial insemination. But success has been spotty, with miscarriages and premature and stillborn deaths from artificial-insemination pregnancies reaching 54 percent.

Of 27 artificial-insemination pregnancies since 1999, eight resulted in miscarriages or stillborn deaths, documents show. An additional six calves died from disease, including from the herpes virus.

Simply to sustain the elephant population, accredited U.S. zoos need to acquire 10 new female elephants each year, according to modeling by scientists. Only three elephants have been born this year inside U.S. zoos, including one Friday at Portland's Oregon Zoo. Eight have died.

At Woodland Park, some zookeepers wanted to stop trying to get Chai pregnant. But others disagreed; Chai was the only fertile elephant left at the zoo. In March 2010, zoo records show, Chai was inseminated for the 104th time.

Last December, Woodland Park zookeepers corralled Chai once more into the restraint chute and over the course of four days performed three artificial-insemination procedures, bringing the total to 112 attempts, zoo records show. None of the three was successful.

Asked in August about the extent of its artificial-insemination program, zoo officials at first said they did not know the specific number. They also maintained they made no such attempts on their elephants before 2005.

But the zoo's own documents, acquired through public-record requests, include an October 1992 zookeeper log that marks the kickoff of its elephant-breeding program: "Artificial Insemination performed today!"

Confronted with the zoo's records, its spokesman, David Schaefer, acknowledged the earlier artificial-insemination attempts. He explained that zoo officials were embarrassed by the early procedures on Chai and did not consider them examples of what the industry now calls "AI."

They now say they have no plans to impregnate 33-year-old Chai.

"We've decided to stop for now," Schaefer said. "But we're not saying never."

Michael J. Berens: mberens@seattletimes.com or 206-464-2288. News researchers Gene Balk and David Turim contributed to this report.