|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thursday, May 13, 2010 - Page updated at 11:41 AM Information in this article, originally published October 1, 2006, was corrected October 2, 2006. A previous version of this story incorrectly identified a Discovery Channel program about Bering Sea crab fishermen. It's "The Deadliest Catch," not "The Most Dangerous Catch." Ecological upheaval on the edge of the ice

ON THE BERING SEA — As the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson steamed toward St. Paul Island, crab fisherman Wayne Baker was holed up in the tiny Alaskan harbor, waiting for a break in the weather. It hadn't been a great season so far. "I've never seen so many blanks," said Baker, who set pots for four days without pulling up a single crab. St. Paul is a speck of land in the Bering Sea, the treacherous expanse of water that separates Siberia and Alaska near the top of the world. Since Russian fur-traders came seeking otter pelts in the 1700s, this northernmost reach of the Pacific Ocean has created fortunes and claimed the lives of mariners drawn by its astounding bounty of marine life. Whales, walruses, seals — one species after another was slaughtered to the verge of extinction, yet a wealth of living resources remained untapped.

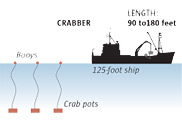

Today the Bering Sea yields half of all seafood harvested in the United States. The annual catch is valued at $1.7 billion. The bulk of that money goes into the pockets of fishermen and processing companies based in Seattle — a 12-day sail from St. Paul. But the nation's richest ocean ecosystem is in the midst of a major upheaval, and scientists suspect global warming is at least partly to blame. Researchers like those who spent a month this spring on the University of Washington's Thompson are trying to figure out what the future holds for the region called America's "fish basket." Crabbers like Baker are already feeling the effects. In the past six years, snow crab catches have dropped 85 percent. Most other crab species are in a similar slump. Overfishing is probably a factor — but not the only one. Biologists also have documented a northward shift of crab populations, away from warming waters in the traditional fishing grounds of the southern Bering Sea. Fur seal numbers are dwindling, despite a 20-year-old ban on commercial hunting. Stellar sea lions were declared endangered in 1997. Seabirds that once flocked to the region by the millions are in precipitous decline. The changes coincide with rising water temperatures and shrinking sea ice cover. "In the Bering Sea ... rapid climate change is apparent, and its impacts significant," scientists concluded in the 2004 Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Not all the impacts are negative — at least from a human perspective. Warmer water favors some species, including pollock, the "money" fish that dwarfs all other fisheries worldwide and winds up primarily in imitation crab, fish sticks and fish burgers. A fleet of ships, mostly from Washington, mines nearly 3 billion pounds of pollock from the Bering Sea each year — the equivalent of 10 pounds for every man, woman and child in the United States. "This is not a clear doomsday story," said George Hunt, a University of Washington ecologist who monitored birds during the Thompson cruise. "If temperatures continue to increase, there's a better than even chance pollock fishing will improve." But there also are indications the Bering Sea's fabled productivity may be diminishing — and that sustained warming could bring nasty surprises. Stocks of most other fish species, including yellowfin sole and Greenland turbot, have been dropping since the late 1970s and federal biologists warned in a report last year that "substantial reductions in total catches may be necessary in the near future." "There will be losers," Hunt said. Study in tough conditions The Thompson called at St. Paul on a blustery day to swap out crew members. The 274-foot ship stood off the treeless island while a skiff shuttled people back and forth. The sky was the color of concrete, the sea like slate. A 3-foot chop hurled stinging water over the small craft's bow. With a wind chill that plunged the temperature into single digits, global warming seemed like a theorist's dream. Few people venture here, but growing numbers have vicariously experienced the Bering Sea's rigors through "The Deadliest Catch." The Discovery Channel show tracks the crews of several crab boats as they battle 60-knot winds, mountainous waves and ice that swallows up their pots. At least 27 fishermen have perished in the Bering Sea over the past decade. Conditions aren't as death-defying on a research ship, but scientists on the first leg of the Thompson's voyage grappled with ice-encrusted equipment and squalls that rocked the ship so violently everyone was forced below decks. Many of these scientists have studied the Bering Sea for 20 years or more. Most work for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, whose Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle monitors the ecosystem, estimates fish populations and figures out how much can be safely harvested. Their trip this spring was focused on a cornerstone of the Bering Sea ecosystem that is beginning to vanish: ice. About 80 percent of the southeastern Bering Sea used to freeze every winter. Since the 1970s, the ice cover has shrunk as average water temperatures have risen by as much as 4 degrees Fahrenheit. Now, the prime fishing grounds remain ice-free most years. The northern Bering Sea still freezes in winter, but floes are thinner and patchy. "You expect normal climate fluctuations, but now it's been about 30 years and we just continue to get warmer," said NOAA biologist Jeff Napp, one of the cruise organizers. Last winter was a cold exception to the trend, with conditions that would have seemed normal several decades ago. But once the ice started melting in late May, it pulled back more rapidly than usual. For creatures adapted to a frozen world, the loss of ice can be catastrophic. Walruses and so-called ice seals haul out on floes to give birth and rear their pups. As the area that freezes each year shrinks, the animals are forced farther north and into deeper water. More walrus pups are being abandoned — a possible sign that adults can't reach the bottom anymore to fetch clams. Short-tailed shearwaters migrate more than 9,000 miles from Australia, trusting the normal interplay of ice, sunlight and water temperatures will guarantee a feast of tiny shrimp when they arrive. In 1997, a half-million of the albatrosslike birds starved to death because off-kilter weather triggered a chalky algae bloom that obscured their prey. Fish also are highly selective about temperature, which varies with the amount of ice. "It only takes a little bit of warming to change from a place with seasonal ice cover to no ice cover," Hunt said. "That's why these high latitudes are expected to be the places where long-term global warming shows up first and has its most profound impacts." The Alaskan Arctic is replete with evidence of global warming, from forest fires to melting permafrost and shifting whale migrations. But those changes mainly affect local residents. What happens in the Bering Sea reaches into the Seattle economy and world seafood markets. The hunt for algae The trick to doing science on sea ice is picking the right floe. It has to be big enough for people to stand on and thick enough to support their weight. Cracks or thin spots can mean a plunge into 35-degree water. From the Thompson's bridge, NOAA oceanographer Edward Cokelet spotted a likely candidate: flat and about the size of a volleyball court. The ship was northwest of St. Paul, sailing between long fingers of ice. Cokelet and two colleagues loaded their gear into a Zodiac and zoomed toward their target. Like a floating dock, the floe bobbed with the swells as Cokelet fired up a gas-powered coring tool. Within minutes, he extracted a cylinder of ice about 2 feet long — the thickness of the floe. After photographing the core, Cokelet sawed it into 4-inch slices. Back on the ship, scientists would melt the slices, analyzing their nutrient content and looking for algae, the microscopic plants that form the basis of the food web. As unlikely as it seems, the presence of ice probably boosts the Bering Sea's productivity. Scientists believe areas that freeze in the winter experience an algae population explosion — called a bloom — early in the spring, thanks to plants that flourish under the ice. The frigid water that time of year limits the number of tiny, algae-eating animals called zooplankton. That means much of the algae falls to the bottom when it dies, a feast for bottom-dwellers and bottom-feeders like worms, crabs, flatfish and diving ducks. Walruses and gray whales also thrive in a bottom-up ecosystem rich in the clams and shrimplike amphipods that make up the bulk of their diets. University of Tennessee biologist Jacqueline Grebmeier has dredged sediment samples from the northern Bering Sea for the past 20 years, as ice cover has shrunk. She's measured a decrease in nutrients and the amount of life the muck can support. Even with this year's extensive ice sheet, productivity levels did not rebound, said Grebmeier, who collected samples during a separate research cruise in late spring. "If we have colder water again for a while, the animals that were there won't necessarily come back," she said. "Once you change an ecosystem, it's very difficult to put it back the way it was." Where ice has vanished, algae don't bloom until later in the spring. By then, the water has warmed slightly and zooplankton are abundant. The little animals gobble up the plants, so less food falls to the bottom. Instead, the zooplankton nourish a food chain that favors fish like pollock and cod and fish-eating mammals like killer whales. "It's a dramatic change, and it's happened in my lifetime," Grebmeier said. Polar cowboys The seal shifted nervously on the ice, craning her neck to get a better look at the creatures approaching from the sea. She probably had never seen humans before. Now, three Zodiacs were buzzing toward her from different directions. Reluctant to abandon her days-old pup, she hesitated too long. The moment the rubber boats hit the ice, biologists camouflaged in white smocks leapt out and raced toward the animals. Wielding what looked like giant butterfly nets, they ensnared the mother, then straddled her back like bull riders. In fact, the group from NOAA's Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle jokingly call themselves "polar cowboys." The 150-pound female bucked and bellowed. Sitting astride his catch, Bob Montgomery slipped a jacket over her eyes. Her struggles subsided. "It's a ribbon seal," he said. "And she's a good mom." The male pup, cloaked in thin, white baby fur, went limp, as if trying to disappear against the snowy backdrop. No creature may be more threatened by the loss of ice in the Bering Sea than the ribbon seal, which is marked with a circular white band that gives it a clownish appearance. Little is known about the species — except its absolute dependence on ice as a platform for breeding and birthing. One of four ice-dependent seal species, ribbon seals lack the wariness of animals that live farther north in polar bear territory. If ice vanishes from the Bering Sea, forcing the seals into the Arctic basin, their prospects are grim. "I think we could be looking at the extinction of ribbon seals within this century," said John Bengtson, director of the marine mammal lab. He was crouched on the ice, mixing epoxy to glue a satellite transmitter to the female's back. The transmitters track the seals' movements until they molt, shedding the instruments along with their tattered fur coats. The NOAA team helped tag the first ribbon seals last year on the Russian side of the Bering Sea. They discovered the animals travel all across the basin, diving up to 1,000 feet to feed. As if on cue, they all headed to the edge of the ice when the water began to freeze in November, probably to haul out and rest. Information on the seals' movements and behavior helps scientists understand their life cycles and design surveys to estimate the species' populations. "We need to start paying attention now," Bengtson said, "or it will be too late." Warming trend at work With binoculars at the ready, the UW's Hunt and fellow ecologist David Hyrenbach kept a lonely vigil on the Thompson's bridge every day, logging each bird they spotted. Their tallies were sparse until the ship drew near the boundary between the continental shelf and the deep basin to the west and south. Nutrients swept up along this undersea cliff sparked a flurry of activity in the water, and gulls, kittiwakes and fulmars dived and wheeled in search of food. The interplay between deep and shallow water is one of the main reasons the Bering Sea supports so much marine life. With water up to 13,000 feet deep, the basin serves as a repository for some of the planet's most nutrient-rich water, delivered there by global currents. The great fisheries occur on the shelf — an area bigger than Washington, Oregon and California combined — where the water is less than 500 feet deep. Sunlight penetrates the vast expanse, nurturing algae. Winds mix nutrients through much of the water column. One of the more disturbing changes in the past 25 years has been a slackening of the summer storms responsible for that mixing — which could lead to an overall drop in the Bering Sea's productivity. Since 1980, summer wind speeds have been well below normal, said Jim Overland, an oceanographer with the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, a co-sponsor of the expedition. But weather in the Bering Sea has always varied wildly. Historical records show cycles of alternating cold and warm conditions that last for roughly a decade, accompanied by corresponding booms and busts in fish populations. Those cycles haven't ended, but there are many signs that a longer-term warming trend is at work as well, Overland said. The current temperature increase extends across the Arctic from Norway to Siberia and Alaska. Temperatures still vary year to year, but there haven't been any major cold spots in the last two decades, he said. The intense warming between 2000 and 2005 also doesn't fit any historic pattern. And even if 2006 marks the start of another cool cycle for the Bering Sea, it almost certainly won't be as pronounced as in the past, said Overland, who has studied Arctic climate for nearly 30 years. "What it will do is slow the rate of warming." Unless carbon-dioxide emissions from cars and industry are sharply curbed, the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment predicts average temperature increases of 5 to 9 degrees Fahrenheit on land and up to 13 degrees over the northern oceans within the next century. None of which is very helpful to folks like Baker, the crab fisherman who sheltered in St. Paul harbor this spring. Bering Sea fisheries Herring: 40 million pounds, $3 million* Halibut: 18.4 million pounds, $53 million* Salmon: 157 million pounds, $78 million* Crab: 43 million pounds, $130 million* Cod and other ground fish: 1.1 billion pounds, $330 million** Pollock: 3.3 billion pounds, $1.1 billion** * Amount paid to fishermen ** Value after primary processing Source: NOAA, Alaska Department of Fish and Game The future of the fisheries Fisheries have always yo-yoed, Baker pointed out. In some years, crabs were plentiful in the eastern Bering Sea. In other years, the action shifted west. "I think they're just going to keep moving," he said, with a shrug. A few industries, like oil and shipping, are preparing for the day when ice-free Arctic seas allow for exploration and commerce. That kind of planning is tough for the fishing industry, said Gunnar Knapp, a University of Alaska economist who studies the seafood business. "They're very aware that global warming could have significant impacts, but the scientists aren't able to give them any firm predictions," he said. "The industry is focused on the here and now." Over the past few years, scientists have discussed what climate change might mean for fishing worldwide. But concrete answers remain elusive because marine ecosystems are still so poorly understood. Even in Alaska, where the fisheries are considered the best-managed in the world, biologists can't predict how a tug on one part of the ecological web will reverberate through the others. Consider the arrowtooth flounder, which has proliferated as the Bering Sea warms. Arrowtooths are big and look like they would be good eating, said Teressa Kandianis, whose Bellingham-based Kodiak Fish Company owns two Alaska trawlers. "But when you go to cook it, the meat just melts." Attempts to find a market for the fish have generally failed, she said. The flounder is also a fierce predator of young fish. Could that serve as a check on expanding pollock populations? Recent surveys measured the first drop in pollock populations in six years, and federal biologists are recommending a 17 percent cut in harvest levels next year. No one knows exactly what's going on, but that's the type of question the researchers on the Thompson hope to be able to answer some day. Kandianis hopes her company will be able to adapt as the mix of fish in the Bering Sea changes. "One species' abundance might go down, but another one typically is going to come up," she said, then paused. "Unless there's nothing there." Sandi Doughton: 206-464-2491 or sdoughton@seattletimes.com Copyright © 2006 The Seattle Times Company Most read articles

|

Seattle Times Special

Miracle Machines: The 21st-Century Snake Oil

The Favor Factory

Confronting Malaria

Pike Place Market

Your Courts, Their Secrets

License to Harm

The Bering Sea

Olympic Sculpture Park |