Originally published June 21, 2014 at 6:49 PM | Page modified June 21, 2014 at 6:50 PM

Pay for performance? It depends on measuring stick

Pay for performance is only as good as the metrics used to determine it. And as a recent study shows, some metrics — including the most popular — are downright ineffective at motivating executives to create shareholder value.

The New York Times

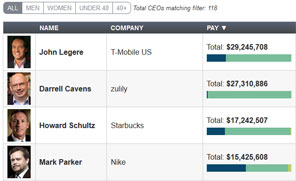

Pulling away: 5 highest-paid CEOs

Stock benefits separated the highest-paid executives of Northwest public companies from the rest.

1John Legere, T-Mobile US

2Darrell Cavens, zulily

3Howard Schultz, Starbucks

4Mark Parker,

Nike

5Spencer Rascoff, Zillow

1John Legere — T-Mobile US

2013 total pay: $29.2 million

Cash pay: $6.6 million

Equity pay: $22.5 million

Market cap (12/31): $29.97 billion

Profit FY 2013: $35 million

Number of employees: 40,000

2Darrell Cavens — zulily

2013 total pay: $27.3 million

Cash pay: $350,000

Equity pay: $26.9 million

Market cap (12/31): $5.13 billion

Profit FY 2013: $12.9 million

Number of employees: 1,110

3Howard Schultz — Starbucks

2013 total pay: $17.2 million

Cash pay: $3.7 million

Equity pay: $13.3 million

Market cap (12/31): $59 billion

Profit FY 2013: $8.3 million

Number of employees: 182,000

4Mark Parker — Nike

2013 total pay: $15.4 million

Cash pay: $7.1 million

Equity pay: $7.7 million

Market cap (12/31): $69.3 billion

Profit FY 2013: $2.5 billion

Number of employees: 48,000

5Spencer Rascoff — Zillow

2013 total pay: $10.6 million

Cash pay: $473.570

Equity pay: $10.1 million

Market cap (12/31): $3.2 billion

Loss FY 2013: $12.5 million

Number of employees: 817

Source: Equilar and SEC documents

Illustration: David Miller / The Seattle Times

More

![]()

Year after year, as executive pay continues its inexorable climb, it’s amusing to watch corporate directors try to justify the piles of shareholder money they throw at the hired help. Check out any proxy filing for these arguments, which usually center on how closely and carefully the executives’ incentive compensation is tied to the performance of company operations.

But pay for performance is only as good as the metrics used to determine it. And as a recent study shows, some metrics — including the most popular — are downright ineffective at motivating executives to create shareholder value.

The study was done by James F. Reda, a veteran compensation consultant, and his associate David M. Schmidt, both of whom are in the human resources and compensation consulting practice at Arthur J. Gallagher & Co.

They analyzed pay metrics used by 195 large companies over the five years ended in December 2012.

By comparing those measurements with moves in these companies’ stock prices, the study identified the common pay metrics that corresponded with above- or below-average performance.

Their analysis will come in handy for investors examining the executive-pay tallies for 2013. As usual, the numbers are staggering: The median compensation for CEOs at the 100 largest companies that have filed so far was $13.9 million, according to the Equilar 100 CEO Pay Study. That’s up 9 percent from 2012.

But investigating the basis of these amounts takes some digging.

Consider Oracle, whose chief executive, Larry Ellison, received $78.4 million, placing him atop our 2013 pay list. Only by reading the company’s proxy do you learn that Oracle determined its incentive compensation — meaning most everything but salary — based on growth in what it calls “non-GAAP pretax profit.”

In Oracle’s lexicon, that means the company’s earnings before income taxes and minus the costs of stock-based compensation, acquisitions, restructurings and other items. In other words, the Oracle number is not based on generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP, and that makes its numbers look better.

Oracle’s approach is just one of many benchmarks that companies can choose. Some boards award incentive pay based on a company’s total shareholder return or earnings-per-share growth; others use return on invested capital or return on equity. Most companies use more than one measure. And all argue that their methods justify the incentive pay they award.

But which measurements work and which don’t?

According to Reda and Schmidt, stocks of companies choosing the most popular gauge — total shareholder return — as a performance metric for at least one year out of the five in the study significantly underperformed stocks of companies using any other benchmarks during the same period.

By contrast, stocks of companies that used earnings-per-share measures based on generally accepted accounting principles outperformed.

The analysis also determined that companies making frequent changes to their pay metrics vastly underperformed those that stuck with their benchmarks.

Among the 195 companies in the study, just more than half — 53 percent — used total shareholder return as a metric. Those companies’ shares had an average loss of 0.18 percent, annualized, over the five-year period. That compares with an average gain of 1.15 percent among all 195 stocks, regardless of the benchmark they used.

Even more striking, stocks of companies that did not use total shareholder return as a measure gained an annualized average of 2.67 percent.

“What this says is companies should look for alternatives to the total shareholder return measure,” Reda said. “They should look for growth drivers that management can control and not do the knee-jerk thing.”

That knee-jerk thing, he said, is total shareholder return, and he said that using it routinely was a mistake.

Interestingly, the study found that stocks of companies using a much less popular metric — earnings-per-share growth — were more likely to outperform.

Only 37 percent of companies used that measure at least once from 2008 to 2012, the study found.

Still, these shares generated a gain of 1.37 percent, annualized, during the five years, above the 1.15 percent average gain across all the companies.

Neither Reda nor Schmidt could say with certainty why the benchmark of total shareholder return seemed so closely linked to lackluster corporate performance. But Reda was willing to speculate on why earnings-per-share measures were less popular in the boardroom. They are harder to manipulate than other measures that burnish results by removing costs from the equation, he said.

“Earnings per share seems to be the best measure, and lots of investors and shareholders think it is important,” Reda said. “But companies hate it. They don’t want to be held accountable for the costs of discontinuing product lines or closing factories.”

Another interesting conclusion from the study is this: Shares of companies that chose a metric and stuck with it generally did better than those of companies that changed their measures.

“Stability of design has value,” Reda said.

Perhaps the study’s clearest message is that one size does not fit all when measuring pay for performance. For instance, not all companies’ stocks underperformed when their managers were judged on total shareholder returns.

Health-care equipment and services companies are an example. The returns of those that used total shareholder return exceeded the average returns of their peers, the study found.

Of the 11 companies studied in that industry, the stocks of the three using total shareholder return generated average annualized gains of 4.4 percent in the period. That compares with 1.9 percent for shares of companies that didn’t use the metric.

Similarly, the use of earnings per share didn’t always translate to stock outperformance, the study found. This was the case in the energy, insurance, media and retailing industries.

As a result, Reda said, boards must design their pay packages with goals that are specific to the company’s strengths and weaknesses, but that will also promote the kind of growth that shareholders want.

“Large companies can be unwieldy,” Reda said. “If management is not really focused on what they need to do, they are unlikely to succeed in getting their houses in order. If you can focus management on things they can control, investors might be better off.”

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!