Originally published June 21, 2014 at 6:43 PM | Page modified June 22, 2014 at 8:12 AM

High cost of soaring executive pay

It is interesting that in the age where jobs are increasingly seen as commodities that can be slashed, sent offshore for cheaper labor, interchanged or automated, only the top executives are considered indispensable.

|

Special to The Seattle Times

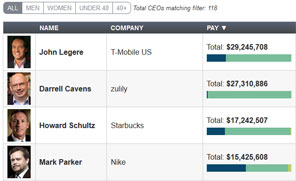

Pulling away: 5 highest-paid CEOs

Stock benefits separated the highest-paid executives of Northwest public companies from the rest.

1John Legere, T-Mobile US

2Darrell Cavens, zulily

3Howard Schultz, Starbucks

4Mark Parker,

Nike

5Spencer Rascoff, Zillow

1John Legere — T-Mobile US

2013 total pay: $29.2 million

Cash pay: $6.6 million

Equity pay: $22.5 million

Market cap (12/31): $29.97 billion

Profit FY 2013: $35 million

Number of employees: 40,000

2Darrell Cavens — zulily

2013 total pay: $27.3 million

Cash pay: $350,000

Equity pay: $26.9 million

Market cap (12/31): $5.13 billion

Profit FY 2013: $12.9 million

Number of employees: 1,110

3Howard Schultz — Starbucks

2013 total pay: $17.2 million

Cash pay: $3.7 million

Equity pay: $13.3 million

Market cap (12/31): $59 billion

Profit FY 2013: $8.3 million

Number of employees: 182,000

4Mark Parker — Nike

2013 total pay: $15.4 million

Cash pay: $7.1 million

Equity pay: $7.7 million

Market cap (12/31): $69.3 billion

Profit FY 2013: $2.5 billion

Number of employees: 48,000

5Spencer Rascoff — Zillow

2013 total pay: $10.6 million

Cash pay: $473.570

Equity pay: $10.1 million

Market cap (12/31): $3.2 billion

Loss FY 2013: $12.5 million

Number of employees: 817

Source: Equilar and SEC documents

Illustration: David Miller / The Seattle Times

More

![]()

Despite some hopeful signs of reform and restraint on executive compensation in the Northwest, we are outliers as usual.

According to the Economic Policy Institute, the average compensation for a chief executive last year was $15.2 million, up 21.7 percent from 2010.

From 1978 to 2013, that pay rose an astonishing 937 percent, adjusted for inflation. The typical worker saw a raise of only 10.2 percent.

CEO comp also rose double the increase in the stock market. It is climbing even relative to the income of the 0.01 percent of the top earners.

Last year, the CEO-to-worker compensation ratio was nearly 296-to-1. Although below the peak of 383.4-to-1 posted in 2000, consider that the ratio was only 20-to-1 in 1965 and 29.9-to-1 in 1978.

Not coincidentally, the American middle class was at its strongest and most secure in the 1960s and 1970s.

No wonder star economist Thomas Piketty cites the astounding rise in executive compensation as a major driver of widening inequality.

The nonbinding “Say on Pay” reform that made Seattle’s Expeditors International rethink its executive comp has made little difference in most cases.

According to the executive-comp consultancy Steven Hall & Partners, 3,363 companies held Say on Pay votes last year. But an “against” vote won in only 73. At the 71 percent of companies where a ”for” vote triumphed, the victory margin was 90 percent or more.

It is interesting that in the age where jobs are increasingly seen as commodities that can be slashed, sent offshore for cheaper labor, interchanged or automated, only the top executives are considered indispensable.

One paper by researchers in Australia, France and the United States implies that shareholders have come to value CEOs more than ever. It doesn’t answer the question of why they believe this.

A big reason, surely, is the rise in the late 1980s of the cult of the star chief executive.

In the real world, CEOs can be quite competent and occasionally visionary (Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos). But they depend upon many lower-level employees to execute with great skill.

Other CEOs can be bumblers and even criminals. (Dennis Kozlowski of Tyco comes to mind.) Yet they have ridden the wave of skyrocketing executive pay anyway.

In 2008, before Washington Mutual became the largest banking failure in American history, ousted Chief Executive Kerry Killinger received $25.1 million in compensation.

Indeed, in the case of Killinger and many others, pay was enhanced by risk taking, even to the point of putting the company in danger of imploding.

Such are the perverse incentives in how pay at the top is decided.

Some of the worst abuses of good ol’ boys and friends of the CEO deciding his or her comp have been sanded away. But plenty of rough edges remain. Doing well in too many cases means keeping the stock price rising by any means. That often collides with doing right by stakeholders such as employees and communities.

For example, a chief executive will be richly rewarded for steering the company into a merger. Shareholders will benefit, too, at least in the short term. But hundreds or thousands of jobs can be lost. Cities and towns can lose their economic crown jewels.

Another big change is the meaning of “shareholder.” Once, it meant ownership with responsibility, a long-term commitment to see the company thrive. Since the 1980s, it has become more of a short stopover by big institutional investors seeking a quick payoff.

Also, even with more independent directors on boards and compensation committees, these people are almost always from the same class as the CEO. They all see the world the same way.

A union member as a director is rare. It would be amazing to see Starbucks appoint a barista to its board. If that were the case, Howard Schultz might not make, according to the AFL-CIO’s Executive Pay Watch, 489 times the average worker’s pay.

There are opportunity costs to these bloated salaries: jobs that aren’t created, productive investments that aren’t made, and research that is curtailed among them.

Perhaps the biggest cost is impossible to calculate. The one where much of big business became unmoored from the notion of a common good. In the 1960s, it would have been unseemly for a big boss to make 296 times more than his workers.

Today, it’s a baseline.

You may reach Jon Talton at jtalton@seattletimes.com

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Also in Business & Technology

Jon Talton comments on economic trends and turning points, putting them into context with people, place and the environment in the Pacific Northwest

jtalton@seattletimes.com