| He helped create the biotech boom and when it went bust, so did he

By Duff Wilson and David Heath

Seattle Times staff reporters

Copyright © 2001 The Seattle Times Company

|

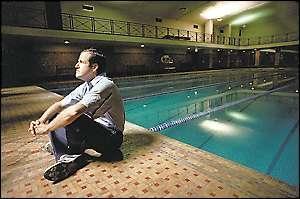

| Harley Soltes / The Seattle Times |

| David Blech exercised in the swimming pool at his Chelsea apartment as therapy for his depression. |

NEW YORK - The father of Seattle's biotechnology industry has a probation officer.

He lives in a modest, cluttered apartment in Manhattan's Chelsea neighborhood, 3,000 miles from the glass-and-steel temples of the companies he helped create. A continent away from the houses of doctors who, with his help, turned their positions with the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center into personal fortunes.

And only two miles but a world away from the $3 million penthouse where he lived in 1992, when he was on Forbes magazine's list of the 400 richest Americans.

Meeting with a Seattle newspaper reporter, David Blech wears sweat pants, a sleeveless T-shirt and beat-up white tennis shoes with loose laces. He looks like a disheveled Billy Crystal, curly hair cut close, jaw unshaven.

He takes lithium for manic depression and has spent time in a mental hospital.

But things could be worse: At least the federal judge who sentenced him for securities fraud in 1999 allowed him to stay out of prison.

Blech's precipitous fall from grace is no more fascinating than his ascension as a brash 24-year-old who turned a family dream into reality. He helped build an industry whose products have saved lives and made lots of money.

And, as a Seattle Times investigation being published this week has revealed, Blech helped create a situation at the Hutchinson Center in which the care of cancer patients might be compromised by business relationships.

The get-rich-quick dream of 1980 - after plastics, before the Internet - was biotechnology. With talk of the potential of a cure for cancer, the industry's economic possibilities seemed unlimited.

Blech, a songwriter and fledgling stockbroker, watched Genentech, a company with no profits and no products, sell shares for $35 apiece and double the price to $70 by the end of its first day on the market.

"I can do that," Blech told his father, a rabbi and stockbroker, and his brother, a public-relations man.

The three started with a name: Genetic Systems.

"The ideal catch-all but say-nothing name for our new biotechnology company," Blech recalls.

Next, they needed to find a scientist brash and respected enough to head the company.

Among their candidates: Dr. Robert Nowinski, a young, rising star at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. They had just read about him in an article entitled "Immunizing Immortality."

They called him, and for some reason - perhaps because he, like the Blechs, was from New York - Nowinski listened.

In fact, he told them, he had already been talking about setting up a company. He'd been in discussions with Bob Johnston, chief executive of Cytogen, and investor Charlie Allen of Allen & Co.

Blech says Nowinski told him, "I'm going into the monoclonal antibody business."

"So am I!" Blech responded. He persuaded Nowinski to fly to New York for a meeting.

Blech's father picked up the Seattle scientist at JFK International Airport and took such a roundabout way from Queens to Manhattan that, Blech recalls, Nowinski was sorry he'd ever come.

Blech concedes that Nowinski thought he'd been taken in by "a bunch of amateurs."

Blech didn't even have a credit card. He was a kid - wiry, fast-talking, high-strung, super-ambitious. In some ways, a lot like the 35-year-old Nowinski.

Blech won Nowinski from Johnston and Allen with the promise the scientist could do good work, get rich and stay close to "The Hutch" in Seattle.

Allen had wanted Nowinski and 11 other Seattle scientists to move to New Brunswick, N.J. Blech told Nowinski that was crazy.

"That was the best observation of my career," Blech said. "It's unusual that two kids from Brooklyn and their rabbi-stockbroker father could get a company away from Bob Johnston and Allen & Co., but we did. We used to call the company `Genetic Balls.' "

The Blechs had $10,000 apiece. Blech says they told Nowinski they'd borrow to put $200,000 in escrow for him to keep if they didn't raise $3 million within a year.

They raised $40 million.

Nowinski was given 1.2 million shares of stock at a penny a share. Under Blech's tutelage, Nowinski sprinkled shares around The Hutch like manna from heaven.

His brilliance and the penny stocks helped Nowinski recruit his boss, Dr. John Hansen, as medical adviser for Genetic Systems and his boss' boss, Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, as a key member of the company's scientific advisory board.

Then Genetic Systems struck a deal with Hutch officials for commercial rights to 37 drugs.

Three of those drugs were antibodies that were to be used in a Hutch experiment called Protocol 126, an experiment in which Hansen and Thomas were involved. As described in The Times earlier this week, that experiment was controversial within The Hutch, with some doctors complaining that the welfare of patients was compromised by the researchers' ties with Genetic Systems.

In 1982, when Genetic Systems went public at $1.25 a share, the Blechs, Nowinski, Hansen and Thomas all made lots of money. Three years later, the company was bought by Bristol-Myers for $10.50 a share.

Bristol-Myers hurried in to buy Genetic Systems for $294 million in stock two weeks after Eli Lilly, its rival, had bought Hybritech, another monoclonal-antibody company, for $350 million. Blech liked to brag that Genetic Systems sold for 15 times its original public-stock value, while Hybritech merely doubled its value.

Blech made $30 million on the Genetic Systems deal. Nowinski's stock at that point was worth more than $10 million and Hansen's $1.8 million. Assuming Thomas had kept his original stake, which is unknown, his share - in Bristol-Myers stock - was worth $1 million.

"I always took great comfort how the scientists made a million dollars each," Blech said.

As Rose Beer, then a company official, recalled, "We had a very high profile at Genetic Systems. Without any due diligence, Bristol Myers came in and bought us for about $300 million. And then did their due diligence. And what Bob (Nowinski) sold was his dream of what this company would be.

"Oh, man, if they only knew!"

They found out soon enough that the dream was brighter than the financial reality. In 1991, Bristol-Myers resold part of the former Genetic Systems for $20 million and closed the other part, taking a $274 million bath.

Despite that, Bristol-Myers has gone up six fold since then, increasing even further the value of the doctors' stock.

Selling vision and credentials

Blech became known as the nation's most aggressive biotech financier. He took high fees and a lot of stock for seed money, and he took the companies public fast.

While most biotechs had one or more products in Food and Drug Administration-sanctioned trials before they took their stock public, most of Blech's did not. That made the scientific studies and credibility of medical doctors on board all the more important.

The Hutch's Thomas, who won a share of the 1990 Nobel Prize for his work on bone-marrow transplants, was recruited by Blech for the advisory boards of three other companies.

Dr. James Bianco, founder of Cell Therapeutics, a company now worth $485 million. |

And Blech helped two other Hutch scientists, Drs. James Bianco and Jack Singer, start Cell Therapeutics Inc.

"Bianco came to us," Blech recalls. "He told us this story about these amazing clinical results he was seeing."

Some scientists doubted the research, which touted unbelievably good results with a little-known drug shielding vital organs from harm during cancer chemotherapy. Blech says he knew the research was thin but he sold the vision and the credentials of the company's supporters, especially Thomas.

"Ultimately, the drug failed," Blech said. "I don't know why." But Cell Therapeutics tried another drug, then another. Recently the company rose from near-death to huge gains with an arsenic drug to fight blood cancers.

"They were constantly reinventing themselves," Blech said. "That's the wonderful part of dealing with (stock in) life and its frailties."

Major deal-maker in biotech

In 1989, the Blechs helped create Icos Corp., joining Nowinski and Dr. Chris Henney, who had left The Hutch to co-found Immunex.

The Blechs put up $1 million of borrowed money. They wanted PaineWebber to sell the stock; PaineWebber wanted the Blechs to recruit George Rathmann, founder and chairman of the largest biotech company in the nation, Amgen, of Thousand Oaks, Calif.

Rathmann had taken Amgen from $4 a share to $60 and sold $190 million in products in 1989.

Ken Lee of Ernst & Young said Rathmann, 65, was "one of the most important guys in biotech in the country." Landing him was a coup for Blech and Nowinski.

"George had a fantastic career at Amgen, you know; he was the king of biotech," Blech said. "Luckily, he had one more deal in him."

The board of Icos was amazing for a start-up company. It included the former chairmen of Citibank (Walter Wriston), IBM (Frank Cary) and General Foods (James Ferguson), a former secretary of commerce (Alexander Trowbridge), and David Blech and his brother, Isaac.

Icos had the largest start-up financing in biotech history, $33 million. The Bothell-based company went public at $8 a share in 1991. David Blech owned 7 percent, and made a quick $10 million.

Rathmann described Blech as a "pure-greed" venture capitalist, and one who was very important to Seattle biotech. "It's because of his very venturesome personality. You have that kind of mindset," he said.

In the next few years, Blech helped set up about 20 other companies, mostly outside the Seattle area, including Celgene of Warren, N.J., with Nowinski, and Incyte Pharmaceuticals of Palo Alto, Calif.

He was a master salesman, whipping out lists of investors and trust funds, spinning academic cachet into cash. He sold hope: You could find a cure and make a mint.

Picking up `fallen angels'

Research doctors from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center started at least 10 major

companies, many with help from The Hutch and New York financiers David and Isaac Blech.

Research doctors from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center started at least 10 major

companies, many with help from The Hutch and New York financiers David and Isaac Blech. |

|

At the height of his power, Blech estimated his personal fortune in 1992 at $310 million.

But Genetic Systems never did make a product to help cure cancer. Neither did Cell Therapeutics.

"I made a lot of money in the companies in Seattle but the products didn't quite get there," Blech said. "So I guess I entered the '90s feeling a little guilty about all that. So I started putting money into `fallen angels.' "

That's how he referred to young biotech companies that had spent at least $100 million on research but didn't have a product ready by the time they were out of money.

Blech picked them up when nobody else would.

"People get tired, you know," he said. "A lot of bright stars become fallen angels before they shine again."

He saved NeoRx of Bothell with $10 million cash, helping it raise $31 million in licensing deals.

He saved Microprobe (now Epoch Pharmaceuticals) of Bothell, personally financing operations for 16 months. He wrote monthly checks and guaranteed the salaries for six executive officers.

He bailed out another dozen companies across the nation. He was sure his name would mean gold.

"I'm not telling you there wasn't an element of greed in it for myself," Blech said. "I'm sure that played a role in it. But my doors were open to everybody - whether it was an Icos with golden management or a NeoRx that was on its ass and needed $10 million to keep the company open. I tried to save both sectors."

When Blech himself fell, though, many looked away.

Things fall apart

The biotech market soured in 1993. Blech, obsessed with buying undervalued biotech stocks, bought more and more on credit. He shifted funds to hide his mounting losses.

Blech stopped taking lithium. "As a manic-depressive, I'd get real high and low, so I'd buy when prices were high and sell when prices were low, the exact opposite what you should," he said.

The Securities and Exchange Commission investigated whether Blech broke the law by giving cheap stock to money managers and others prior to public offerings. That would inflate the price. Blech denied any impropriety.

For a time, Blech-backed companies held up under the collapse. Then he ran out of cash and the short-sellers pounced.

The first sign of deep trouble was in April 1994, when Blech had to sell his 24 percent stake in NeoRx to avoid a margin call by Citibank on $40 million in loans.

Afterwards, Blech bragged about the money he'd made on NeoRx anyway and the $150 million he claimed was held in trusts nobody could touch no matter what happened to the market, the financial newspaper Barron's reported.

Falling deeper and deeper in debt, Blech admits, he executed sham and unauthorized stock sales. It was outright criminal activity and he knew it, but he said he couldn't stop.

D. Blech and Co. failed to open its doors on Sept. 22, 1994 - referred to on Wall Street as "Blech Thursday." At least 13 stocks for which Blech was the underwriter declined by 23 percent or more that day. One fell 64 percent. The whole biotech sector sagged.

More than 300 brokers lost their jobs when the firm collapsed, and Blech stood sobbing in his trading room at the end of the day.

"A few days after D. Blech & Co. closed its doors on September 22, 1994, Blech entered the hospital due to an emotional breakdown. He never returned to the firm's offices. Within days of the firm's collapse, Blech's wife filed for divorce," according to a National Association of Securities Dealers report. Blech hadn't told his wife he was forging her signature on documents.

The SEC said investors and broker-dealers took $22.5 million in losses because of Blech's stock manipulations.

As the SEC developed criminal charges against Blech, he turned informant. Lloyd Schwed, a Florida attorney for four brokers who sued Blech, was arrested in August 1996 and charged with shaking down Blech by offering to withhold tapes subpoenaed in the SEC investigation. Schwed told Blech he would destroy two especially damaging tapes if Blech settled the suit with a big payment. Blech had worn a wire for the feds.

In April 1998, Blech was charged with the illegal security actions that led to "Blech Thursday." He pleaded guilty to two counts of criminal fraud. He faced up to 97 months in prison.

He refused to seek an insanity plea, though, even after a court-appointed psychiatrist said manic depression had contributed to his crimes.

Federal prosecutors suggested leniency because Blech had helped them. In October 1999, U.S. District Judge Kevin Duffy sentenced Blech to five years' probation and community service.

The National Association of Securities Dealers fined Blech $20,000, censured him and barred him from associating with NASD members in the future. In addition, the SEC, four former brokers and a class of investors all filed lawsuits against Blech.

Blech had never been well-known in Seattle, and none of this was even reported in the daily newspapers in the city where he'd set up several biotechs and manipulated stocks in others. Blech has not been mentioned in The Seattle Times since 1996, and in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer since 1994.

Hoping for a comeback

Today, Blech is supported by his second wife, Margie, a graphic designer and aspiring actress.

He is trying to sell a manuscript of his life story - "Million Dollar Dreamer" - but publishers aren't buying.

Sally Richardson, president of St. Martin's Press, wrote to him recently: "People don't like David Blech, they don't root for him, and we don't think they would buy his book."

Blech says he thinks about his rise and fall every day. His early times with Nowinski were the best, he says: so young, so easy.

But it's been a long time since Blech has heard from Nowinski, who lives north of Seattle and recently left Vax Gen, a company trying to develop an AIDS vaccine.

Rathmann is about the only one who calls Blech from Seattle anymore. Rathmann and Bianco wrote letters of support to the judge in Blech's federal trial.

Blech hopes to make a comeback someday. Not now, but soon. He's restless. He has a part-time secretary in his home office, a desk in the corner off the living room. He promises to never borrow money again, but watches the market closely.

"I believe I have learned from my mistakes," Blech wrote recently. "I feel good about my legacy. I have helped create over $15 billion in biotech market value, and have been associated with several products which are currently being used in the treatment of AIDS and cancer.

"But, at 44, I am still too young to retire. I may have one more go at it in me. This time, I would try to do it in a more measured way, with only one or two biotech companies. I would not try to save the world."

Duff Wilson's phone number is 206-464-2288. His e-mail address is dwilson@seattletimes.com.

David Heath's phone message number is 206-464-2136. His e-mail address is dheath@seattletimes.com.

|