Copyright © 1997 The Seattle Times Company

This story originally appeared Sunday, July 13, 1997 in Pacific Magazine.

The day Seattle's ship came in: part 1

by Ross Anderson

Seattle Times staff reporter

The Klondike Gold rush is a story lived 100 years ago this week by thousands of people -- loggers and lawyers, cowboys and clerks. Here's a look back to the day Seattle's ship came in.

Friday, July 16, 1897.

The late afternoon sun slants between the red brick walls of First Avenue, where wisps of steam hover over puddles left by a midday shower. Throngs of busy people dodge streetcars and horsedrawn wagons and carts -- a 19th-century rush hour.

Joe Smith finishes his 10-hour day at the warehouse, wearily dons his threadbare suitcoat and derby and steps out into First Avenue. He takes a breath of Northwest air spiced with the smells of saltwater and sawdust, wood smoke and horse manure. He barely notices the clatter of hundreds of footsteps, the clip-clop of horses and wagon wheels bouncing over worn cobblestones, the clanks and hisses of a steam derrick laboring in the next block.

But Joe Smith is well aware of the charged atmosphere of Gold.

"FAIRY TALE ON THE KLONDIKE!" shouts a 10-year-old newsboy on the corner of First and Jackson. "TOM LIPPY COMES HOME A GOLD TYCOON! READ IT IN THE TIMES."

First Avenue is abuzz. Tom Lippy a tycoon? Our Tom Lippy?

"Pshaw!" Joe mutters to himself. "Fairy tale, indeed. He's heard it all before: Gold on the Fraser River, the bonanza at Monte Cristo, gold at Fortymile on the Yukon River. Just a couple of weeks ago, it was gold at the foot of Mount Si, a stone's throw from Seattle!"

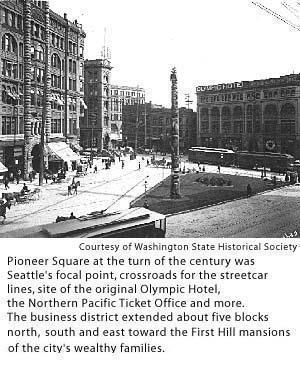

Given the sun and the relatively clear air after a spell of clouds and drizzle, Joe decides to save streetcar fare and walk home. He strolls north, through Pioneer Square, which throbs with the heartbeat of a raw, wide-open frontier town longing to become a city.

Not just a city, but the biggest and best in the Pacific Northwest, which folks here believe to be their destiny. Downtown streets are cobbled, lined with ambitious, multi-story brick buildings, most of which have risen in the eight years since the disastrous fire of 1889. Fueled in large part by the recent arrival of Jim Hill's Great Northern Railroad, the city has rebuilt and nearly doubled its population to 65,000. About one quarter of them live right here, in or near downtown in hundreds of boarding houses, residence hotels, flophouses or a smattering of pioneer homes.

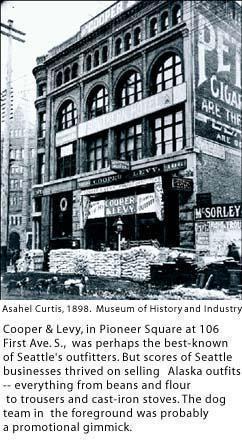

Joe makes his way through bustling Pioneer Square, past the workaday Cooper & Levy store and its huge sign advertising "Alaska outfits," past the ever-so-fashionable City of Paris and the grand mansion built by old Henry Yesler. He weaves among hundreds of strangers -- men like himself, trying to look professional and prosperous in their dark suits and hats, past women in floor-length skirts, their parasols tilted toward the afternoon sun. He brushes past carpenters and bricklayers with their rolled-up sleeves, tow-headed kids hawking the evening papers, farmers driving carts loaded with vegetables or milk or live chickens.

At First and Columbia, he stops to check the progress on the massive new Colman Building, where two steam derricks work sunup to sundown, lifting tons of timbers and Tenino stone to workers on the upper floors.

This city is on the brink of something big. Maybe it will be salmon canneries, already thriving up and down the Sound. Maybe a new demand for Northwest cedar, fir and spruce, whose supplies still seem infinite. Maybe it will be China and the Far East. Or Alaska and the Golden North.

But for Joe Smith, the excitement of living on the edge of the continent is twinged by the struggle to make a living at all.

Just 48 months ago, things looked brighter. At age 30, and newly arrived from the family farm in Iowa, he was making $3 a day as an assistant manager and bookkeeper at a downtown bank. He and his bride planned to buy a house -- maybe up the north streetcar line at Green Lake, or down the Rainier Valley line at Columbia City, where a small house on an acre could be had for $200 -- maybe less.

Then came The Panic of '93, the nation's worst economic crisis to date. More than a downturn, it was a near-collapse of confidence in the monetary system itself. Hundreds of banks failed, including Joe's, throwing him and his dreams on the muddy streets. Depression gripped the nation, and particularly the West.

Since then Joe has struggled to make ends meet, $1.50 a day as a millworker in Ballard, a day laborer, and now as a warehouse clerk. His income is barely enough to cover his $5 a month rent for a single room in a clapboard, two-story rooming house near Lake Union, several blocks beyond where the cobblestones give way to makeshift planks strewn across mud streets.

Further up Second Avenue, Joe walks past more downtown stores -- Frederick, Nelson and Munro, Rochester Clothing, Newhall and Co., and facing each other across Pike Street, the Bon Marche and The Fair. As he walks up Stewart Street toward home, he glares off to First Hill and the mansions of James Hoge, Judge Cornelius Hanford, Morgan Carkeek and the rest of the new rich, whose garden parties, tennis tournaments and out-of-town guests are covered breathlessly in the local society columns.

To Joe, those mansions are impossible dreams, even more remote than the merchandise in the windows along First Avenue. He is going nowhere.

Joe gives in and spends the two cents for an afternoon Times. "FAIRY TALE," reads the main headline:

The Fabulous Wealth of the Clondyke

Tom Lippy's Luck

Seattle man takes out $65,000

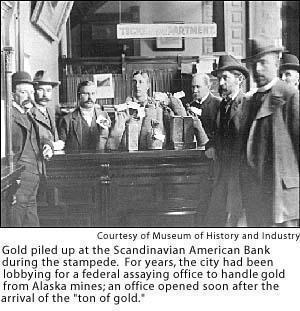

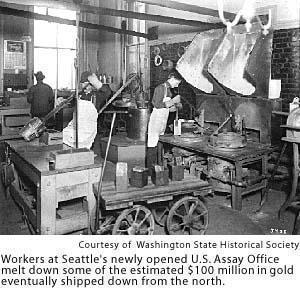

The story is datelined San Francisco, where the steamer Excelsior arrived on Thursday from St. Michaels, Alaska, delivering a group of miners from someplace called "Dawson City" in Canada's Yukon Territory. Lippy, the dispatch reads, is among them, and he has returned a wealthy man. In all, about 40 passengers are carrying a fabulous $750,000 treasure in gold dust and nuggets.

And there is the rumor of more to come -- another steamer, bearing an even more fabulous cargo.

And this one is due in Seattle.

My gawd! Joe says to himself. He's seen the newspaper advertisements for the goldfields of Cook Inlet and the Yukon. He's seen the prospectors packing up their outfits down at Cooper & Levy. He's even heard about leather bags filled with gold dust being carried off Alaska steamers.

But Tom Lippy, the bookish schoolteacher from the YMCA, now worth $65,000! If Lippy can get find his fortune up there, then anybody can.

On to Saturday, July 17, 1897

Anderson's description of 1897 Seattle is based on information from Roger Sale's "Seattle: Past to Present," Pierre Berton's "The Klondike Fever," Murray Morgan's "Skid Road" and Seattle Times editions from June and July of 1897. In addition, Kathryn Morse, a University of Washington Ph.D. candidate who studies the Klondike, reviewed the article for historical accuracy.

|