|

Copyright © 1997 The Seattle Times Company

This story first appeared Sunday, July 13, 1997 in Pacific Magazine

The day Seattle's ship came in: part 2

by Ross Anderson

Seattle Times staff reporter

The Klondike Gold rush is a story lived 100 years ago this week by thousands of people -- loggers and lawyers, cowboys and clerks. Here's a look back to the day Seattle's ship came in.

Saturday, July 17, 1897

Joe rises with the first light, crawls back into the same threadbare suit and slips out the door. The air of electricity has intensified. People are striding, even running down Stewart toward downtown and Pioneer Square. Joe joins the throng, walking, then jogging past the clothing stores to First Avenue and down to the waterfront.

Along the way, newsboys hawk the morning paper. Joe stops to glance at the headline:

GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!

68 Rich Men on

the Steamer Portland.

STACKS OF YELLOW METAL!

The morning paper has scooped its competition by sending reporters north on a tugboat to meet the Portland, interview the passengers, then race back to town to be in print when the steamer arrives. The strategy works. The edition is an immediate sensation.

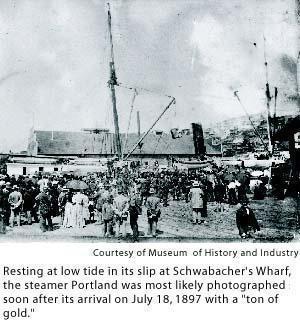

Alerted by the headlines, the crowd has swarmed onto Schwabacher's Wharf, where the Portland has just pulled in through the morning mist. From Joe's vantage point, the steamer is remarkably prosaic -- a planked hull with square bow, boxy cabins fore and aft with lifeboats stowed above, two crude cranes above the cargo holds and one blunt stack amidships, still belching smoke. Crew and passengers line the rail next to the wharf while the lines are secured to the dock.

"Show us the gold!" somebody shouts, and a couple of bearded passengers hoist their sacks and grin broadly to the cheers of the crowd.

Minutes later, Joe watches as the gangplank is lowered, launching the oddest parade in Northwest history. Down the plank marches a motley assemblage of grizzled humanity, each man hefting one or more sacks or suitcases jammed with gold dust and nuggets.

One miner nonchalantly reports he has $100,000 in dust and nuggets wrapped in a blanket, and promptly hires two men to help haul it away. Joe Bergeoin, once a Seattle logger, says he has $15,000 and is going back next spring for more. John Wilkinson of Nanaimo, B.C., struggles with the weight of $25,000 in a leather sack whose handle snaps as he lifts if off the deck. Joseph Cazla of Montana carries $30,000 worth, and adds with a shrug that he drank up many times that before leaving Dawson.

And then there's William Stanley, the former Seattle bookseller, whose wife has been taking in laundry and living on wild blueberries in Anacortes, waiting for her husband's return. They are now worth a staggering $112,000. Mrs. Stanley promptly checks into the Palace Hotel, throws out her tattered wardrobe and goes on a shopping spree.

The morning paper reports that the Portland is delivering a "ton of gold," a catchphrase that will endure for a century. For hours, Joe lingers at Schwabacher's Wharf, listening to stories of the weary prospectors. The word is out: Dawson and the Klondike are the richest goldfields in history. Nuggets are simply plucked from the gravel in shallow streams. Even those who don't have rich claims can make $15 a day, plus room and board, working for those who do.

C. Worden, Stanley's partner, tells a Times reporter: "I went to the Yukon a year ago. We have an interest in a claim on Bonanza Creek. How much did I bring out? Well, put down any amount. It will be all right. And you won't be far out of the way."

Scooped by the competition, the evening Times tries to treat the story conservatively, billing the cargo as "half a ton," and warning that "there should be no haste, but every person going to the Upper Yukon should move with deliberation, care and forethought."

But the stampede is on. Nobody can stop it.

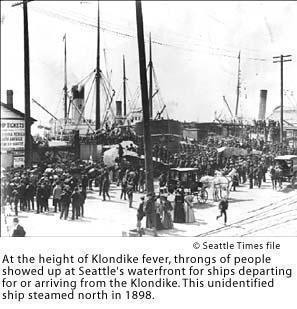

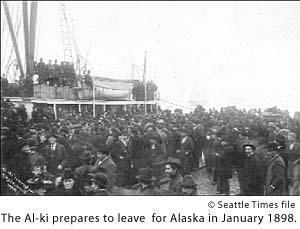

The Western Union office is flooded with telegrams, incoming and outgoing. Dozens, then hundreds, of local workers determine to catch the next northbound steamer. "Scotty" Stewart, a popular downtown hackdriver, drops his reins and books passage on the steamer Alki. A downtown grocer closes his doors and buys a ticket on the same boat.

Big Jim Burns, a Seattle cop on the waterfront beat, collects $2,500 from a $125 investment in a friend's Klondike claim, prompting dozens of his fellow officers to turn in their badges and billyclubs and head north. Newspaper classifieds are immediately filled with ads from prospective miners seeking financial backers, or vice versa.

Former Gov. John McGraw, a U.S. Senate candidate, decides to head for the goldfields instead. Seattle's mayor, W.D. Wood, attending a convention in San Francisco, reads the news and wires his resignation; he will raise some money, buy a decrepit steamer, fill it with prospectors and gear and sail for the Yukon.

Hours later, Joe wanders back through town, up Stewart Street to his ramshackle rooming house. Still in a daze, he climbs up to his room and announces to his wife:

"I'm going to the Klondike."

Joe Smith is fiction, part of this reporter's imagination. But it is a story lived 100 years ago this week by thousands of real people -- loggers and lawyers, cowboys and clerks. During the following 18 months, Klondike historian Pierre Berton estimates, an estimated 100,000 people from around the world set out for the Yukon. Of those, 30,000 to 40,000 actually got there. About half of them actually looked for gold, about 4,000 found some, and perhaps a few hundred got rich.

Many died. They froze to death on Chilkoot Pass, were caught in snow avalanches, drowned in the mighty Yukon, succumbed to dysentery or other diseases in Dawson. Others gave up, went home or made smaller fortunes exploiting fellow gold-seekers -- which was the key to Seattle's civic fortune.

Beginning July 17, 1897, Seattle launched an unprecedented public relations campaign that established the city as the only logical starting point for a Klondike expedition. The campaign worked. The majority of goldseekers rode Jim Hill's rails to Seattle, bought all or most of their ton of supplies here, and shipped north on a Seattle-based steamer. By the following spring, Berton writes, Seattle merchants had sold Klondike goods worth $25 million -- far more than the value of the gold dug from the Klondike during the same period.

The effects on Seattle were dramatic, immediate and profound. Word spread that no goldseeker should head north with less than a ton of supplies -- enough flour, beans, bacon and more to survive a year in the wilderness. By Monday, the local newspapers were jammed with ads from outfitters, grocers, steamship companies, miners seeking financial backers, or backers seeking miners. Collapsible stoves that hadn't moved a week earlier became "Klondyke stoves" and sold out in hours. Prices of groceries and outdoor equipment began to spiral upward.

It was as if Microsoft went public, Boeing sold a hundred 747s, and the Mariners won a World Series -- all in the same day.

The Klondike Gold Rush was fabulously rich, and mercifully short. By early 1899, the goldfields were controlled by corporate syndicates and the prospectors were moving on to golder pastures in Nome or Fairbanks. But the Klondike remained embedded in the Northwest psyche.

In a sense, Seattle itself arrived on the steamer Portland. Within hours, the Indian name of an obscure Canadian river was a household word across the continent and beyond. A few weeks later, Seattle's was equally recognizable. The railroad had arrived, but the Klondike filled Jim Hill's railcars with people and goods.

When hundreds of New Yorkers set out for the goldfields, most routed themselves through Seattle. Rival Tacoma had its own railroad and steamships, but its star was fading; Tacoma's population remained flat while Seattle's doubled from 42,837 in 1890 to 80,671 in 1900. The older and more conservative Portland continued to grow, but not as fast as Seattle, which by 1910 had become a metropolis of 237,000 people -- largest in the region.

Beginning with the summer of '97, Seattle became the economic capital of Alaska and The North, shipping point for its supplies, headquarters for its salmon-packing and shipping companies, even its government offices. Seventy-five years later, history would repeat itself as Seattle made millions more as the staging port for the Alaska pipeline.

Perhaps all this would have happened anyway, with no help from the steamer Portland and its fabled ton of gold. But, for better or worse, that nondescript steamer packed with grizzled zillionaires set the stage for a booming city that eventually would produce the likes of Bill Boeing and Bill Gates.

And that's a lot of high-stakes accidents for one sodden seaport.

Anderson's description of 1897 Seattle is based on information from Roger Sale's "Seattle: Past to Present," Pierre Berton's "The Klondike Fever," Murray Morgan's "Skid Road" and Seattle Times editions from June and July of 1897. In addition, Kathryn Morse, a University of Washington Ph.D. candidate who studies the Klondike, reviewed the article for historical accuracy.

|