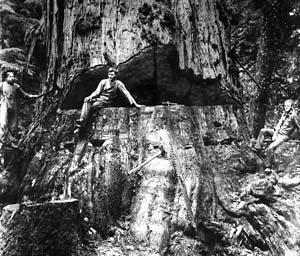

Historic Washington logging. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

Historic Washington logging. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

As a young man, Jim Stevens worked in Idaho logging camps and then hit the road, hoboing from job to job throughout the Northwest. At night around the bunkhouse stove, he listened to the lore of the woods -- old Wobbly songs and tall tales of Paul Bunyan.

In 1948, he described his own writing hand: "Here it rests on a yellow tablet, holding a pencil, awaiting the spirit and the word. I know this hand too well. The spread from thumb butt sidewise is over most of the tablet's eight-inch width. The palm is sheathed with calluses from teaming, logging, pitching wheat bundles, bucking sacks of wheat. There are two bulged knuckles and other marks of a fighting fist."

Brawler and laborer turned poet, Stevens became the guardian of Northwest logging history and interpreted it for his readers.

He had heard stories of "the determined men of the woods and the mines . . . men singing Joe Hill hymns and giving testimony on Big Bill Haywood at street meetings . . . making Haywood general secretary of the Industrial Workers of the World, then hoboing home to agitate and organize. One Big Union." Stevens' lyric celebration of the Wobblies reminded Northwesterners of their free-spirited inheritance from those rambling men of hard hands and tough minds.

Stevens became the dean of Northwest writers. He also was publicist for the West Coast Lumberman's Association, trying to protect the forest industries he loved and preserve the rich heritage of the woods. All his life, this bespectacled, mild-looking man celebrated rugged loggers who read Walt Whitman's poetry by firelight.