By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

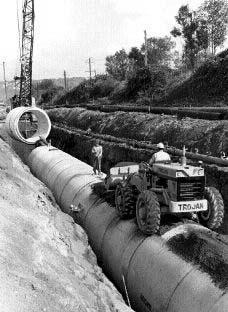

In nine years, Metro installed more than 100 miles of tunnels and four treatment plants to

handle sewage that had grown to an average of 100 million gallons a day by 1968. Above, pipe was laid to a new plant in Renton.

In nine years, Metro installed more than 100 miles of tunnels and four treatment plants to

handle sewage that had grown to an average of 100 million gallons a day by 1968. Above, pipe was laid to a new plant in Renton.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

SIGNS POSTED ALONG THE SHORES OF LAKE WASHINGTON WARNED OF FOUL WATER, and mothers all

over Puget Sound worried whether to allow their children to play on local beaches. Seattle sightseers peered uncertainly into

the distance, finding thick, gray haze obscuring views of the nearby Olympic Mountains.

The problem was pollution. This "Charmed Land" of the Northwest, praised worldwide for its scenic beauty and recreational attractions, suddenly found itself confronting the unforeseen effects of rapid population growth and industrial development during the postwar, baby boom years. An environmental crisis loomed, threatening to undermine the region's pristine image along with the health of its residents.

Warning signs had appeared by 1945 when the newly formed State Pollution Commission received complaints from residents along Fauntleroy Bay, south of Seattle, that sewer lines emptied into the Sound -- "discharging geysers of sewage at the low-tide line."

Investigators found that only one "woefully inadequate" treatment plant served the entire city, and no less than 14 pipes dumped raw

waste directly into area waters. The commission's director warned that all of Seattle's saltwater beaches were "highly dangerous."

Also polluted was the heavily industrialized Duwamish River, where fish could not survive, and floating solids and scum were an everyday sight.

Lumber and steel mills lining the river also belched noxious smoke and fumes into the air. City officials protested they were doing their

best to clean up the mess, but the commission thought otherwise, charging that "Seattle, the metropolis of the Northwest, has given

no indication of taking any action towards the abatement of its pollution."

Yet the problem was not Seattle's alone; air and water pollution grew worse throughout the 1950s as huge suburban developments along Lake Washington's northern and eastern shores added environmental pressures. Hurriedly built septic systems leaked into feeder streams, and the bacterial count in parts of the lake rose to dangerous levels, forcing numerous beach closures.

As Puget Soundıs population grew, so did its pollution. Citizens urged local governments to collaborate in cleaning

it up, and a grass-roots campaign, including the poster above, persuaded voters to pass Metro in 1958.

Here,

children in Lake Washington scooped up algae caused by treated effluent from small municipal sewage plants. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

Recognizing the need for planning and infrastructure to cope with the growth, 10 new cities along the lakeshore incorporated within a decade. Most built their own plants to treat sewage. But soon an explosion of green-blue algae, feeding on the nutrient-rich processed waste from these plants, added slime and stench to the lake's environmental problems.

Air quality also declined. A University of Washington study released in 1951 had found the area's particulate count -- dust and smoke deposits in the atmosphere -- higher than Los Angeles'. Industry was the greatest contributor, but suburbanization made matters worse. Commuters helped swell King County's new automobile registrations by more than 100,000 in five years, increasing exhaust emissions and congestion.

As early as 1952 civic groups such as the League of Women Voters and the Municipal League urged Seattle and outlying communities to deal collaboratively with area problems. Attempts to modify the county form of government to meet these goals failed, so a citizens committee, formed in 1956, came up with a new approach -- a metropolitan municipal corporation. Metro -- the Municipality of Metropolitan Seattle -- would be run by a council of city and county officials with the power to oversee critical regional services including waste disposal, transportation, parks and planning.

The legislature passed an enabling act for Metro, but the measure lost when it first appeared on the ballot in March 1958. A majority of Seattleites voted yes only to find county residents had turned it down. The project was too big, too costly, and a threat to local government, critics argued.

But citizens groups retooled the proposition, focusing only on sewage disposal and shrinking Metro's jurisdiction. Volunteers rushed to set up speakers bureaus, get endorsements and blanket the area with fliers and posters featuring a photograph of local children unable to swim in polluted waters. On the day before the Sept. 9 election, 5,000 Metro Marchers rang doorbells to get out the vote.

These remarkable volunteer efforts succeeded. Metro passed, and within a month its 16-member council began planning a comprehensive sewage-treatment program.

James Ellis. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

By July 1966 when community activist and Metro guiding light James Ellis helped open the West Point treatment facility, the largest of four built by the $140 million project, Metro was rapidly nearing its goal of making the polluted waters of Lake Washington and Puget Sound clean again.

In his dedication speech, Ellis recognized in Metro supporters "the quality of the long look and the will to serve," but wondered rhetorically whether such far-sighted civic commitment would extend to other environmental problems -- smog, traffic and urban blight.

To deal with smog and congestion, city buses tried to lure commuters with free rides, left, and visionaries offered ideas for more elaborate transit plans.

Ellis had reason to be concerned. Voters in 1962 had turned down a proposal to give Metro transit authority, and proponents of a regional transportation plan emphasizing new freeway construction battled with those who favored rail.

A committee led by Ellis introduced its own plan, Forward Thrust, combining an extensive rail system with other urban needs including parks, low-income housing and even a domed stadium. The community embraced some of these measures in the 1968 election, but regional mass transit failed to win support, failing again two years later as the local economy nosedived.

Voters finally turned back to Metro in 1972, authorizing development of a regional bus system, but the idealism and civic commitment to solve other long-term environmental problems was left to the future.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.