By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

|

Local activists turned to demonstrations and other nonviolent protests to achieve integration during the early 1960s. Protesters, above, demonstrated for more black participation in Seattle's Human Rights Commission during a City Council hearing in July 1963. | Photo Credit: Bruce McKim / Seattle Times

SEATTLE IS "ONE OF THE FEW CITIES LEFT IN AMERICA WHICH CAN SOLVE ITS RACIAL PROBLEM BEFORE IT BECOMES UNSOLVABLE." So testified the Rev. Dr. John Adams, pastor of the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, at a U.S. Civil Rights Commission hearing in 1966.

Seattle had long considered itself a liberal city in light of its early labor radicalism and multicultural heritage. Yet while the country struggled to change centuries-old patterns of discrimination, Seattle, too, was shaken from its complacency and forced to deal with racial tensions.

Local civil-rights leaders initially focused on integration and equal opportunity, but by the end of the turbulent 1960s emphasis had shifted to issues of community pride and development. The interests of Seattle's African Americans, who were most visible in the fight for equality, occasionally clashed with those of Native American, Latino and Asian citizens. But ultimately, many strategies that proved effective for black activists aided other minority groups.

Local civil-rights leaders initially focused on integration and equal opportunity, but by the end of the turbulent 1960s emphasis had shifted to issues of community pride and development. The interests of Seattle's African Americans, who were most visible in the fight for equality, occasionally clashed with those of Native American, Latino and Asian citizens. But ultimately, many strategies that proved effective for black activists aided other minority groups.

During World War II, city leaders had ignored racial problems in the interest of national defense. But in the postwar era the potential for violence rose with the changing makeup of Seattle's population and increasing competition for jobs and housing. As early as 1944 the mayor created the Civic Unity Committee, an interracial council of respected, politically moderate citizens who mediated discriminatory practices and educated the public on race issues.

The group helped ease the Japanese back into local society after relocation ended, and worked to stop discrimination in housing, especially for African Americans.

Before the war, fewer than 4,000 blacks lived in Seattle, but that number expanded by more than 400 percent between 1940 and 1950 as jobs became available in defense industries. African Americans were originally dispersed throughout the city, but increasingly became concentrated in parts of the Central Area.

To address the segregation, an open-housing movement began; activists encouraged homeowners and realty companies to cooperate voluntarily. Yet innovative programs like the Fair Housing Listing Service, which coordinated efforts to find minority housing outside the Central Area, often met with hostility. When Sidney Gerber, a white businessman, built "Harmony Homes" for black residents in segregated neighborhoods, only one real-estate broker agreed to list them, and The Times refused to run any ads.

Community leaders counseled patience, and local chapters of established civil-rights groups such as the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People worked within the existing power structure to further their goals. But as the fight for racial justice heated up from Alabama to Washington, D.C., Seattle activists faced new tactical choices.

|

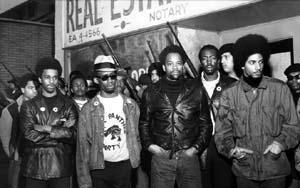

Black-power advocates, especially the Black Panther Party, were known for their militant rhetoric. Seattle's Black Panther chapter, left, did display weapons to protest the shooting death of a member in 1968. |

| Yet the group, led by Aaron Dixon, right, also sponsored community services including free breakfast programs in the Central Area. Photo Credits: Greg Gilbert and Vic Condiotty, Seattle Times. |

|

WHEN DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. scheduled a Seattle appearance in November 1961, protesters feared he would "espouse radical and perhaps subversive causes," and one local church refused to rent its sanctuary for his speech. But after King's visit, a Times reporter found his equal-rights "militancy" tempered with "restraint and dignity."

Local activists soon adopted his nonviolent use of sit-ins, boycotts and demonstrations in their campaign for a fair-housing ordinance. City Council delays prompted Seattle's first large-scale protest march as clerics Mance Jackson and Samuel McKinney led 400 to City Hall in July 1963; 300 more staged a sit-in at council chambers, and arrests led to larger demonstrations. The council finally passed an open-housing ordinance in October 1963 after intense lobbying by Seattle's only Asian councilman, Wing Luke. However, voters later defeated a referendum on the measure by more than 2 to 1.

This setback only increased the agitation to stop housing discrimination, and protest also grew over segregated schools and unfair hiring practices. The Central Area Civil Rights Committee, with leaders from Seattle's major religious and equal-rights groups, promoted civil disobedience to achieve integration.

This setback only increased the agitation to stop housing discrimination, and protest also grew over segregated schools and unfair hiring practices. The Central Area Civil Rights Committee, with leaders from Seattle's major religious and equal-rights groups, promoted civil disobedience to achieve integration.

But as parents increasingly protested mandatory busing and the closure of neighborhood schools, Seattle's black community began to splinter over goals. In April 1967 Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, spoke in Seattle, attacking integrationists as a "small chosen class."

The "black power" goals of Carmichael and others -- pride in heritage and community development -- quickly impressed the local civil-rights movement. Old-line organizations turned to community-building; a new coalition, the United Black Front, united 50 groups dedicated to black-power goals. The UW's Black Student Union, formed in 1968, pushed for a black-studies department as well as active recruitment of minority students and staff.

To outsiders, the gun-toting Black Panthers symbolized the aggressiveness of black power, but their tutoring and free breakfast programs had greater impact within the black community than their hostile rhetoric.

Racial incidents did increase, however, and there was some violence. In 1969, Seattle Urban League director Edwin Pratt was shot to death at his home in what the county sheriff initially called a "political assassination," although the killers were never found.

Militants distrusted the government, but federal funding proved a boon to their community-development ideals. Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty supported initiatives such as the Central Area Motivation Program, providing job projects, study centers and recreation. Model Cities money brought neighborhood rehabilitation.

During the troubled 1960s, Seattle made progress toward understanding its racial problems, although solutions remained contested ground for years to come.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.