By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

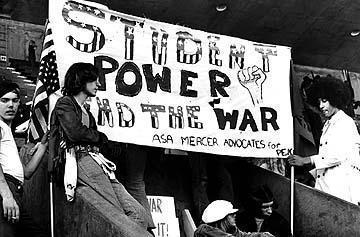

In the fall of 1970, a diverse coalition of students and other young people organized

throughout Seattle to protest the war in Vietnam.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

U.S.INVOLVEMENT IN VIETNAM BEGAN QUIETLY ENOUGH, one of many similar

Cold War adventures. In the early 1950s, the Central Intelligence Agency aided the French struggle to

retain control of Vietnam against Ho Chi Minh's Vietminh guerrillas. By 1956, the French had given up and

Vietnam was partitioned; by 1960, the Vietminh had reorganized as the Viet Cong or National Liberation Front.

In early 1961, about 700 Americans were stationed in South Vietnam. By 1965, 185,000 American troops were there.

Meanwhile, the leading edge of the baby boom hit adolescence. Their parents proudly beckoned them to the future -- the college degree and corporate ascent, marriage and a family, the split-level and station wagon. But many American children of affluence rebelled against their own privilege and their parents' values.

To the boomers, American society seemed sick. As young people matured in the 1960s, they joined or created their own political protest, and invented a counterculture. Their coming of age briefly brought together kids from many races, from every class who shared nothing but their youth and their outrage. And a smattering of idealism.

In 1967, the Open Door Clinic in the University District began

as a volunteer effort to counsel, heal and feed street kids who had streamed to the District.

In 1967, the Open Door Clinic in the University District began

as a volunteer effort to counsel, heal and feed street kids who had streamed to the District.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

I

N THE NATIONAL 1969 MOBILIZATION AGAINST THE VIETNAM WAR, SEATTLE'S MARCH ORGANIZERS

QUIXOTICALLY URGED THE DEMONSTRATORS TO CARRY PAPER FLOWERS and "engage shoppers

in Westlake Mall in discussions about the war and repression." Radical Weathermen sneered,

"Dig it. For us, this isn't a peace march, it's a war march. . . . The time has come to

Bring the War Home to Seattle."

And to the University of Washington, that "most deadly machine," as a Radical Youth Movement mimeo described the school.

At the UW, calls to discontinue academic credit for the Reserve Officers Training Corps were followed by demands to oust the program from campus. Likewise, recruiters from Weyerhaeuser -- "who rape the land with chainsaws" -- and the Dow Chemical Co. -- "murderous war profiteers" -- were blocked by protesters at the Loew Hall Placement Center.

In March 1970, the UW Black Student Union, joined by the Seattle Liberation Front, the radical Weathermen movement and hundreds of unaffiliated students, protested the U's ongoing athletic relationship with Brigham Young University. Claiming that the Mormon Church "ran" BYU and advocated white supremacy, BSU called on the university to sever ties that sanctioned those policies.

A rally of about 1,000 students sent a delegation to Executive Vice President John Hogness with their demands, but he told them a decision was four or five weeks away. Frustration boiled into violence.

Around 200 chanting demonstrators invaded the Old Quad, leaving a trail of damage. But many thousands of students who fully supported the BSU cause were unwilling to pass beyond rallies and teach-ins to civil disobedience, let alone violence. The invasion of Cambodia and open war on student protesters would change that.

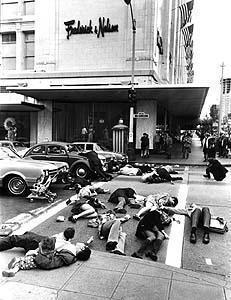

. . . In May 1970, 150 demonstrators staged a silent "die-in" at Fifth Avenue and Pine Street to protest the shipping of nerve gas through Seattle to Oregon. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

On April 30, 1970, President Richard Nixon ordered an assault into neutral Cambodia to cut supply lines to Viet Cong guerrillas. Protest against broadening the war rocked nearly every campus. A graduate student working in the UW's Thomson Hall surprised an arsonist who calmly confessed to campus police that he hoped to set the building ablaze to protest the U.S. action.

That Sunday, Ohio's governor sent National Guard troops to control protests at Kent State University. Within 24 hours, four students lay dead of gunshot wounds.

On Tuesday, May 5, 1970, the UW Daily announced that a strike had begun to honor the dead and bring home the living. No more business as usual; it was time to shut the place down and work to end the war. That day, 5,000 students "took the freeway," headed for downtown; next day, 10,000 kids marched from campus to downtown, joined along the way by hundreds of Seattle residents.

On Tuesday, May 5, 1970, the UW Daily announced that a strike had begun to honor the dead and bring home the living. No more business as usual; it was time to shut the place down and work to end the war. That day, 5,000 students "took the freeway," headed for downtown; next day, 10,000 kids marched from campus to downtown, joined along the way by hundreds of Seattle residents.

On campus, the Strike Coalition took over the old Physics Annex, and set up a mimeograph machine and a day-care program. Radicals made fitful attempts to barricade campus entrances, occupy buildings and establish a Free University. KUOW was liberated as Radio Free Seattle, and strike organizers demanded an end to war-related research on campus.

The Times angered conservative readers who quickly grew "sick and tired" of lavish coverage of the UW Strike -- including dozens of photos and interviews with student leaders. But the paper's editorial voice deplored violence and disrespect and upheld patience and restraint, urging student demonstrators to come to their senses and return to class at once.

But across the nation, the state of siege continued. On

May 15, highway patrolmen shot to death two black students in their dorm at Mississipi's Jackson State University.

But by February 1971, a UW rally to protest the spread of the war into Laos was marked by heckling and bickering. The center couldn't hold, and the coalition fell apart.

Nonetheless, America had undergone a vast change. The '60s were made by kids from the affluent, self-indulgent '50s of hula hoops and poodle skirts. Critics said kids only cared about sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. But for many it was much more.

Nonetheless, America had undergone a vast change. The '60s were made by kids from the affluent, self-indulgent '50s of hula hoops and poodle skirts. Critics said kids only cared about sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll. But for many it was much more.

While not all young people were radicalized, nearly all were sensitized to the issues that radicals raised. The anti-war coalition brought together supporters for the United Farm Workers grape boycott, Earth Day and the National Organization for Women. The movement forced attention to the disproportionate number of poor young men of color who were fighting the war in Asia. Most of all, the youth culture and protest movement insisted on the need for an ethical, humane basis for the American way at home and abroad.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research, writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.