By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

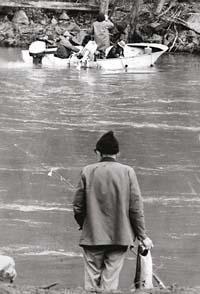

A sport fisherman stands opposite Indians netting steelhead on the Puyallup River -- a symbol of the division over fishing rights. Photo Credit: Tommy Thompson / Seattle Times.

SALMON HAVE ALWAYS SUSTAINED NORTHWEST INDIAN PEOPLES,

but over time they have also become the object of "uncommon controversy."

The battle over the right to fish for salmon was a classic Western confrontation:

a showdown between the state government and Indians that, like so many past struggles,

took on symbolic proportions.

At issue were differing notions of tradition and sovereignty -- and,

ultimately, the efforts of Indians to take control of their own cultural identity and destiny.

On Feb. 12, 1974, U.S. District Judge George Boldt handed down a decision

that represented a measure of victory for Indian peoples of the Northwest.

The case was United States vs. Washington, originally filed in September

1970 by the federal government, and joined by 14 Indian tribes. The controversy

centered on the degree to which the state of Washington could regulate the fishing

rights of Indians who were parties to treaties concluded by federal negotiators.

When Washington first became a U.S. territory in 1853,

more than 8,000 Indians lived west of the Cascade Mountains and north of the Columbia River.

Isaac Ingalls Stevens, the first territorial governor, was also named superintendent of

Indian affairs. Under this authority, Stevens began to negotiate with native peoples of

the region to cede part of their land and establish reservations.

Within two years, Stevens concluded six treaties with Washington Indians,

beginning with the treaty of Medicine Creek in 1854. While ultimately conveying nearly 64 million

acres to the government, most of the treaties also recognized that Indians retained certain rights,

including "the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations . . .

in common with all citizens of the Territory."

In 1974, the federal judge George Boldt ruled that local Indians were

entitled to 50 percent of the

harvestable salmon and steelhead.

In 1974, the federal judge George Boldt ruled that local Indians were

entitled to 50 percent of the

harvestable salmon and steelhead.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

FOR THE NEXT 120 YEARS, HOWEVER, THE MEANING OF THAT PHRASE WAS CONTESTED

as non-Indian settlers and then the state of Washington fought to control access to the region's

rich fisheries. Sportsmen and commercial fishermen concerned about jobs adamantly argued that

treaties should give the Indians no special rights; the state claimed the power to regulate Indian

fishing, interpreting "in common with all citizens" to mean that Indians must also be subject

to state control.

Native peoples, in contrast, believed that the treaty rights entitled them

to fish unimpeded at any of their "usual and accustomed" places, both on and off their reservations.

These differing interpretations periodically led to conflict. Open warfare had

followed within a year of the original treaty signings, but most later battles took place

in the courtroom or in the halls of government.

By the 1930s and '40s, conservation became a major issue as both

the state fisheries and game departments blamed declining salmon and steelhead runs on

Indian netting and disregard for state restrictions. The Indians countered that commercial

fishing, dam-building and logging had really been responsible, ruining the livelihood of many.

The great grandson of a treaty signer, Robert Satiacum joined other

Indian leaders to battle the state over fishing rights.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

AMONG EARLY INDIAN ACTIVISTS WAS ROBERT SATIACUM, a Puyallup who challenged

the state's right

to regulate steelhead gillnetting on the Puyallup River. The 1954 arrest of Satiacum and

James Young for illegal fishing became a test case, leading to a Washington Supreme

Court decision prohibiting state restrictions on Indian off-reservation fishing unless

necessary for conservation.

Satiacum, always controversial, continued his protests, becoming,

as one Times reporter called him, "the greatest thorn in the side of state game officials."

But Satiacum was not alone. Indian fishermen at Frank's Landing on the Nisqually

as well as other local rivers tested the state's resolve to enforce fishing laws. And the state

responded, sometimes with guerrilla-style tactics.

In early January 1962, the Game Department began a series of surprise deployments

on the Nisqually River south of Tacoma, using walkie-talkies and a reconnaissance plane to

track Indian fishermen, arrest violators and seize their boats and gear. The Indians retaliated

with their own adaptation of 1960s civil disobedience -- fish-ins -- to protest interference with

treaty rights.

The war also continued in the media as a parade of the famous came to support the Indian cause:

Marlon Brando was arrested in 1964 while "helping some Indian friends fish" on the Puyallup River,

and comedian Dick Gregory was jailed for joining the Indians in illegal fishing.

Charges flew that the "outside agitators" were the trouble, and their

presence caused dissension within Indian communities. But the increased militancy of some

local Indian groups such as the Survival of American Indians Association actually foreshadowed

the rise of Indian resistance movements nationwide.

Attempts were made to link Indian fishing rights to established civil-rights

causes. Attorney Jack Tanner, regional director of the NAACP and later a federal judge,

represented many Indians arrested for illegal fishing.

Yet many Puget Sound native peoples saw their cause as unique. Red Power

meant sovereign, not equal, rights -- and the ability to reconnect to a lost past.

The battle went beyond fishing as Indian activists not only tested state restrictions on

reservation cigarette and fireworks sales, but also fought to reclaim federal land at

Fort Lawton and to establish an Indian Center in Seattle.

A teepee encampment was set up near the state capitol in 1968

to dramatize the Indians' struggle for sovereign rights. Photo Credit: Associated Press.

BITTER EXCHANGES AND SOME VIOLENCE ACCOMPANIED INDIAN GAINS.

A militant leader, Hank Adams, claimed he was shot by white vigilantes while fishing,

although law enforcement doubted his story. In September 1970, Tacoma police used

tear gas and clubs to arrest 59 protesters camped on the Puyallup.

The escalating hostility finally brought the 1970 federal suit against the state.

More than three years of investigation and courtroom testimony culminated in the decision by Boldt,

who interpreted Indian fishing "in common with all citizens" to mean an equal share of the catch.

This 50-50 formula, allowing Indian fishermen half of all harvestable salmon and steelhead,

affirmed Indian rights in both tradition and law.

In 1971, an Indian Affairs Task Force had issued a report observing

that the conflict "has done more to inflame racial hatred and entrench hostility and

suspicion against the state on the part of Indians than any other issue." But the Boldt

decision caused equally bad feelings on the part of non-Indian fishermen. Tensions continued

as sportsmen saw their catches limited, commercial fishermen lost their livelihood, and game

officials decried the consequences to fisheries conservation.

And though a 1979 Supreme Court ruling upholding Boldt's decision has

encouraged the state and the Indians to work together, the salmon continue to be a symbol

of uncommon cultural and legal controversy.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research, writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.