By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

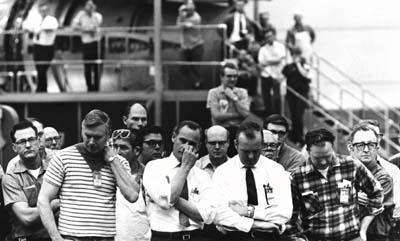

In March 1971, workers at the Boeing Supersonic Transport Division listened to

Boeing vice president Lowell Mickelwait announce the final U.S. Senate rejection

of funding for the SST program.

Photo Credit: Pete Liddell / Seattle Times.

ON NEW YEAR'S DAY 1970, SEATTLE READERS OPENED THEIR TIMES to find the customary annual reviews and predictions. Times guest columnist Miner Baker, president of Seattle-First National Bank, recalled "the Soaring '60s" in which the booming Puget Sound economy "lived up to every promise and then some."

But Baker noted that Boeing's workforce had declined in 1969 to

about 80,000 from a 1968 high of more than 100,000; he warned readers that 1970 would be

"a painful year of readjustment" to a decade of modest prosperity dependent on the "continued

growth in diversified manufacturing."

For 20 years, optimists had claimed a growing industrial versatility,

but the region's economic health remained stubbornly pegged to the fortunes of The Boeing Co.

In The Times, the biggest news story of 1969 was the introduction of the 747, the world's

largest commercial jet. In 1970, the Puget Sound economy was still a one-trick pony;

reality would prove far more dire than Baker's forecast.

By late 1971, the Boeing workforce plummeted to 32,500, and local

economic indicators were in freefall. Battered by the misfortunes of the area's largest

employer and by a national business slump coupled with inflation, the region entered

"the longest and deepest recession since the Great Depression," as a Times writer put it in 1975.

In November 1971, D.B. Cooper hijacks a Northwest jetliner, demanding $200,000 in ransom. He parachutes from the plane, never to be seen again, and becomes a folk hero of the grim 1970s. Sketch at right.

In the early 1970s, the U.S. economy was torn between guns and butter,

struggling to pay for the Great Society's social programs while waging the war in Southeast Asia.

Federal deficit spending rose, as did inflation and interest rates; economic growth slowed and

employment fell. Confronted with "stagflation" -- an extraordinary combination of rising prices

and economic stagnation -- Richard Nixon's administration cut taxes, raised interest rates and

devalued the dollar in quick succession.

Nothing worked, and the energy crisis delivered the final, crippling blow.

The world's industrial economy depended on Middle East oil, quadrupling consumption between

1950 and 1970. But in 1973, U.S. military support for Israel prompted the Organization of

Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to embargo crude oil and then to raise prices.

Acute shortages of heating oil and gasoline resulted, and the price of crude oil

skyrocketed. By 1979, it would cost $30 a barrel.

At home, Boeing sales had soared in the '60s when air carriers eagerly

built their fleets of 707s, 727s and 737s, but suddenly there were more seats than

passengers to fill them. Sales of the new 747 and the older family of jetliners were slow.

In 1970, the company began a 17-month period without a single new order from any U.S. airline.

In March 1971, the U.S. Senate rejected further funding to develop Boeing's SST, the supersonic

transport with commercial and military applications. Then, the energy crisis hit,

driving up the cost of flying.

The mock-up of the SST, was sent to a Florida museum.

Photo Credit: Associated Press.

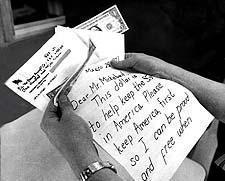

A student's letter was among many sent to Boeing offering sympathy and money

for the SST. Nearly $1 million was sent, but returned after the final cut. Photo Credit: Associated Press.

A student's letter was among many sent to Boeing offering sympathy and money

for the SST. Nearly $1 million was sent, but returned after the final cut. Photo Credit: Associated Press.

AS THE HARD TIMES CONTINUED, UNEMPLOYMENT BENEFITS WERE EXHAUSTED,

extended, then exhausted again;

federal food stamps and local Neighbors in Need food banks met basic human needs.

Seattle's Crisis Clinic phone volunteers counseled men and women coping with the despair

of joblessness. As the area's birthrate fell, the suicide rate rose dramatically; an

anti-suicide net was deployed on the Space Needle, and there were calls for a similar safeguard

on the Aurora Bridge.

In 1973, a drought brought hydroelectric brownouts, and the ongoing oil crisis

forced long waits to buy increasingly expensive gasoline. To a state starved for power, nuclear

energy posed an appealing alternative, and the Washington Public Power Supply System (WPPSS) began

construction of five nuclear-power plants. But in the mid-'70s, everything still depended on oil.

Consumer prices rose 12 percent in 1974 alone. Local housewives organized a

boycott to protest the rising cost of beef, and Seattle-area butchers sold horsemeat roasts and

ground buffalo. The Times' Dorothy Neighbors obliged readers with recipes for chili made with

buffalo and for cheap, starchy main dishes -- Depression fare.

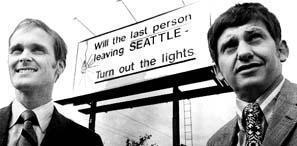

In 1971, Bob McDonald and Jim Youngren's

billboard satirized local gloom-and-doom.

Photo Credit: Greg Gilbert / Seattle Times.

AFTER A GOOD YEAR IN 1972, THE BEAR MARKET OF THE MID-'70S HIT,

AND THE DOW JONES INDUSTRIAL INDEX FELL 47 PERCENT IN 1973 AND '74,

victim of the inflation-recession double punch. Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy

Carter met the energy crisis with calls to self-discipline and countered stagflation

with an array of tweaks to the economy. But 1980 interest rates stood at nearly 20 percent,

inflation was in double digits and unemployment hovered at 8 percent.

Down-sized, Boeing was resurgent by 1980. But the region's fishing, forest, mining,

agricultural and shipbuilding industries found it difficult to rebound. For them, economic

ills had been compounded by foreign competition, labor disputes and environmental legislation.

Few noticed the signs of Seattle's coming high-tech boom; the cost of the 1970s had been too high.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.