Asian Seattle called the International District home, gathering in such places as this Chinese hall to talk old-country politics.Photo Credit: Craig Fujii / Seattle Times.

BETWEEN 1970 AND 1990, SEATTLE'S POPULATION FELL BY 3 PERCENT

while suburban King County's grew by 57 percent. City folk fled to country homes,

hoping to escape their fears of urban crime, blight and school decline.

Then, in the late 1970s, the siren song of the Eastside high-tech boom drew talented engineers nationwide; in three short years, the average price of a single-family home outside the city more than doubled, to $72,200 in 1980. Subdivisions spread across the Eastside, platted overnight, it seemed, in horse pastures and woodlots.

Suddenly, political discourse and café chat was all about the risks, benefits and rivalries of local growth -- about ways to control suburban sprawl and urban density; how to preserve Kent farmlands and downtown Seattle, to make great parks, schools, and museums; how to manage change, provide emergency medical service and develop public-transportation systems.

In 1975, Harper's declared Seattle America's most livable city, and The Times strengthened its coverage of city neighborhoods and politics. But the paper also added suburban bureaus to better meet the needs of readers and compete more effectively against hometown dailies such as The Journal American. For the first time in nearly a hundred years of publication, The Times diligently courted readers outside the city, acknowledging the suburban momentum.

Every metropolitan institution -- the press, shops, zoo and aquarium, buses,

politics -- offered another venue for Seattle and King County's struggle for primacy.

And, for a time, it seemed that Seattle was bound to lose. In 1972, suburban activists

rallied to encourage the secession of east King County to form "Cascade County"

and escape from bankrolling the central city. As an organizer explained,

"The people out here don't want to pay for the problems of metropolitan Seattle --

they don't want to pay for a domed stadium or rapid transit."

Rallying to protect their community identity,

Asian Americans picketed the Kingdome ground-breaking in 1972. Photo Credit: Associated Press.

Rallying to protect their community identity,

Asian Americans picketed the Kingdome ground-breaking in 1972. Photo Credit: Associated Press.

IN 1972, KING COUNTY'S STADIUM WAS ALREADY UNDER CONSTRUCTION.

The city neighborhood most affected by the Kingdome was the International District.

Throughout the years of construction, many Asian-Americans dreaded the stadium's impact,

worrying with community spokesman Willard Jue that "it will be the end of Chinatown."

To some Seattleites, there was little to lose. The "ID" wasn't a

neighborhood at all, they argued, just inner-city blight. They pointed to

rundown hotels such as the Atlas, closed by municipal order for violations of public safety

in 15 out of 21 possible categories. Maybe, they hoped, the Kingdome would finish what

the Freeway had started, and this shabby urban village would just disappear.

But when the Dome opened in 1976, the ID was undergoing a sweeping

neighborhood revival. Contagion from newly revitalized Pioneer Square encouraged rescue

of the threatened ID by its sons and daughters. As artist George Tsutakawa put it,

"I hung around this area most of my life -- our family's business was in the middle of it."

Restaurateur and Councilwoman Ruby Chow echoed, "Chinatown represents our elders' blood, sweat

and tears. We need it for our youth so they can understand their culture."

By 1976, the Seattle Chinatown-International District Preservation and Development

Authority was in place. The Wing Luke Museum was nearly a decade old, interpreting Asian Seattle.

Hing Hay Park had opened; next door, plans were under way to restore the venerable Bush Hotel.

In 1980, local gardeners reclaimed 50 vegetable plots from a hillside blackberry tangle; in 1981,

the landmark Nippon Kan Theatre reopened. The changing city had brought opportunities, and the ID

entered the 1980s with a new sense of common ground.

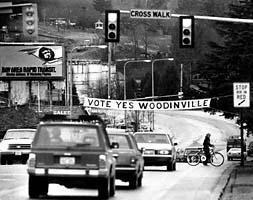

For decades, Woodinville had been a one-horse town where country people shopped,

sent their kids to school and worshipped.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

ON THE EASTSIDE, THE STEADY MARCH OF SUBDIVISIONS THREATENED SUBURBAN REFUGEES

who had fled the city for "rural" homes on half-acres, like many in the unincorporated Woodinville

area of King County. Most hoped to preserve Woodinville's country charm, and worried that their

community would be consumed piecemeal by Kirkland, Bothell and Redmond.

Bothell soon declared its intention to annex more than 130 acres in northwest

Woodinville, and local activists placed a proposal for cityhood on the 1986 ballot.

The Woodinville No! Committee feared that incorporation would sanction unbridled growth;

the Woodinville Yes! Committee was convinced that only incorporation could provide for orderly

development.

In 1986, Woodinville cityhood failed by just over 30 votes; in 1989,

incorporation was defeated again, by only 14 votes.

The following year, King County named Woodinville to a list of sites for

an interim jail, and pro-incorporation forces gained overnight energy. "Other towns were able

to say, 'No, thank you,' to the county," said a Woodinville Yes! backer, "and all we could say was,

'Please, don't.' " But the jail controversy drew enough attention to boost support for getting

incorporation on the ballot once again.

A Times editorial favored cityhood, arguing, "The natural evolution of a place

where people settle and business thrives is toward . . . taking control of the future by opting

to keep decisions close to home rather than in downtown Seattle at the County Courthouse."

By 1992, Woodinville's future hung in the balance, awaiting absentee ballots.

In that year of Perot populism, opponents hoped that voters would reject "one more layer of

local government." But the third time proved the charm and incorporation passed, 853 to

796. With this slender mandate, the new city girded itself for the 1990s.

Fighting for control of their civic destiny,

Woodinville residents campaigned for cityhood in 1989.

Photo Credit: Mike Siegel / Seattle Times.

Fighting for control of their civic destiny,

Woodinville residents campaigned for cityhood in 1989.

Photo Credit: Mike Siegel / Seattle Times.

BY 1994, HAND-WRINGING OVER THE DEATH OF SEATTLE PROVED PREMATURE as

the city's population rebounded to surpass the 1970 level. Drawn by the city's

superb cultural opportunities and embraced by its strong neighborhoods, families,

young professionals and retired folk continued to make their homes in Beacon Hill,

Wallingford and Capitol Hill, Georgetown, Ballard and West Seattle -- all around the town.

Chinatown's resurgence and Woodinville's emergence provide dramatic bookends to

1980s growing pains. From 1970s community councils to Vision Seattle's successful

CAP initiative in 1989 to regulate downtown high-rises, local activists have demonstrated a

rare blend of realism and optimism, determination and creativity. Success or failure,

grassroots activism has proven the distinctive saving grace of this metropolitan area.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.