By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

To view the first story, continue scrolling.

At left, this photograph of Charles Lindbergh Jr., age 19 months, was taken two weeks before his kidnapping in 1932.

Photo Credit: Associated Press.

Note: This page is broken into two parts -- an overall exploration of crime and the Depression,

and a more focused look at a local kidnapping incident that sparked national media attention.

To view the second story ("True-crime tale"), click the graphic to the right.

But they didn't scale back their dreams. The '30s abounded with get-rich-quick schemes;

with enticing ads to "Earn Big Dough At Home!" by cutting keys or casting concrete flower pots.

The public delighted in stories about lunch-counter waitresses "discovered" by Hollywood moguls; about

heiresses marrying delivery boys and wealthy playboys eloping with their manicurists.

THE WAITRESS, THE DELIVERY BOY AND THE MANICURIST BECAME FOLK HEROES, darlings of the

Sunday supplement. When earning an honest living grew harder, making a killing took on a special glamour.

In the drab 1930s, Americans fell in love with luck, and they became intrigued by

criminals who defied the odds to make their own lucky breaks: John Dillinger, "Pretty Boy" Floyd,

Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. But they were drawn, too, to the darkest side of crime.

Local reporting catered to these fascinations but carefully presented crime

as a great American drama in which a wild spree always ended with stern justice. A stock cast

of characters appeared in one crime story after another: the dashing criminal, the tempting floozy,

the hapless victim, the criminal's evil companions, and his loyal wife or mother. Sentimental

sob-sister commentary intensified these tragedies of violence and defiance, trial and punishment.

At right, John Dillinger.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

THE ERLAND'S POINT MASS MURDER was a local crime story,

a morality tale out of the heart of the '30s.

On March 29, 1934, intruders burst through the door of a beachfront home near Port Orchard,

intent on robbery. It was the middle of the night, but the house was ablaze with light as five friends

played pinochle, danced and drank beer. The robbers quickly bound and gagged their victims, ransacking the

house for jewelry, rifling pockets and handbags for cash.

A sixth party-goer, returning with more beer, startled the intruders.

Sizing up the situation, he fought violently for his life.

Three days later, neighbors were alerted by three barking dogs shut up in a victim's car.

The police found the house wrecked, its walls splashed with blood. Four men and two women had been murdered --

shot, stabbed, bludgeoned -- but the murderers' trail had grown cold. Local police were baffled,

and The Times invited readers to mail in their own solutions to the Erland's Point mystery, offering

$20 for the best letters.

On March 31,1934, six people are found murdered in the Port Orchard beach house

of Frank and Anna Flieder. The photograph at left shows the Flieders, far left, with two other

victims, Peggy and Eugene Chenevert.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

In October 1935 --19 months after the murders -- shipyard worker Leo Hall was charged with

first-degree murder. His accuser was Peggy Paulos, who confessed to being Hall's companion the night

of the murders. Hall was handsome and well-spoken, and he steadfastly denied the murders,

insisting he had been simply keeping an eye on Paulos because he owed a jailhouse favor to her husband.

Paulos claimed Hall had talked her into robbing the house, and admitted she was eager enough

for the money. But she ran off, she said, when the killing began.

Hall's mother tearfully maintained that her son was innocent, that he had once studied

for the priesthood, that Peggy Paulos was a liar. After a circus of a trial, Hall was convicted.

At right, Doma, The Seattle Times' daily columnist on astrology and psychology, analyzed Leo Hall's face

and handwriting, concluding they showed general criminal tendencies.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

WHEN LEO HALL WAS HANGED IN SEPTEMBER OF 1936, 100 witnesses attended his execution. His final hours were detailed in The Times -- the failed appeal, quiet visits with a priest, his last meal, his last words. Calm and confident, Hall claimed innocence of the horrible murders in the Erland's Point beach house through the end of his life.

George Weyerhaeuser, 9. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

NINE-YEAR-OLD GEORGE

WEYERHAEUSER WAS KIDNAPPED in May 1935, walking home from school in

Tacoma. A ransom note from "The Egoist" demanding $200,000 was

published in The Times, warning the child's distraught parents:

" . . . A slip on your part will be just too bad for someone else. We know what we are doing, we have it all planned. . . .We don't want to hurt anyone if we can get out of it. So if you just follow the rules as they are lain down by us you will have the one you love back home in a week's time if you care about them $200,000 worth."

THE WEYERHAEUSER FAMILY COMMUNICATED WITH THE KIDNAPPERS by

classified ads in The Post-Intelligencer, delicately referred to by The Times as "another local newspaper."

The ransom was paid and -- after eight days -- the kidnappers released the boy before dawn on a lonely

road in Issaquah. He walked until he came to Louis Bonifas' farm, where the family fed him breakfast

and piled into their battered car for the ride to the nearest telephone. At 6:30 a.m., Bonifas phoned

the Tacoma Police from a Renton gas station, telling them, "I have the Weyerhaeuser boy," and got back

in his car to drive him to Tacoma.

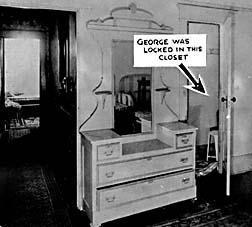

The Times ran this photo marked to show the closet where Weyerhaeuser was held captive.

The Times ran this photo marked to show the closet where Weyerhaeuser was held captive.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

BUT TIMES GOLF EDITOR JOHN DREHER ENDED UP BRINGING GEORGE WEYERHAEUSER HOME,

and also got the scoop of the year. The news of Bonifas' call to the Tacoma Police had leaked quickly,

and cops and reporters were combing the roads from Tacoma to Issaquah, trying to find the farmer's Model

T Ford. Dreher called a taxi and, acting on a hunch, intercepted Bonifas.

Dreher hustled George into his taxi. To slip through the dragnet,

the reporter laid on the floor and encouraged the boy to stretch out on the seat,

below window level. They chatted all the way to the Weyerhaeuser home in Tacoma.

By mid-morning, young George Weyerhaeuser was home again, and Johnny Dreher

was working on his exclusive story, which ran copyrighted on The Times' front page

through the day's many extra editions.

The serial numbers of the bills in the ransom

were published and, within weeks, the three kidnappers

had been arrested. They would be tried, convicted and sentenced to prison.

And young George would grow up to chair the company that bears his name.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research, writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of Seattle Public Library.