By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

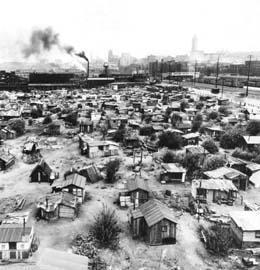

In 1931, homeless men in Seattle took possession of this 9-acre tract belonging to the Seattle Port Commission,

building 50 shacks of scrap lumber within two weeks. The population of Seattle's Hooverville, named after President Herbert Hoover, varied from a summer low of 1,000 to 2,200 in the winter. Hooverville was demolished in 1941

for the construction of Piers C and D, where wartime ships moored to load supplies. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

In 1931, homeless men in Seattle took possession of this 9-acre tract belonging to the Seattle Port Commission,

building 50 shacks of scrap lumber within two weeks. The population of Seattle's Hooverville, named after President Herbert Hoover, varied from a summer low of 1,000 to 2,200 in the winter. Hooverville was demolished in 1941

for the construction of Piers C and D, where wartime ships moored to load supplies. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1929, THE SEATTLE TIMES APPEALED TO THE LOCAL ELITE --

the newspaper's politics were conservative, its morality incorruptible, its economics confident.

Many Times advertisements sold affluence and exquisite taste as hallmarks of

the Pacific Northwest way of life. Discreet ads urged Seattle's gentlemen to purchase their golf

togs or their business suiting from the city's distinguished haberdashers.

Seattle ladies were invited to choose their evening dresses at Helen Igoe's exclusive shop.

Elegant residential developments, cigarettes, yachts, jewelry, automobiles -- the ads breathed a subtle snobbery.

And the 1929 newspaper featured a daily business section that had grown from a half-page

at the end of World War I to four full pages. The Business and Financial Department listed closing

prices on the New York Stock, Curb, and Bond markets, as well as on the growing Seattle Stock Exchange.

The section's editor, Paul Lovering, wrote an advice column for readers, many of them

new to investing. He explained bears and bulls, shorting a stock and buying on margin. Brokers advertised

in the financial pages, promising readers peace of mind as well as appreciation of capital and growth of income.

As the great 1920s bull market charged ahead, it came to seem that only fools would not

get rich in America. Here in Seattle, we would all live in Broadmoor, all drive Cadillacs, all wear

Paris originals -- you just had to get into the market right now! Ordinary people raised money, however they could,

to buy shares in the American dream.

But the economy was fragile; mad speculation had driven the market, not value.

Throughout October 1929, the Stock Market skidded, recovering only to plunge once again,

deeper and deeper, its chart a metaphor for the failing health of the economy.

The Great Crash came home to Seattle when a local stockbroker took his own life --

it was headline news in The Times. But C.B. Blethen, Times publisher, wrote front-page editorials to

reassure his readers that "Business is all right," that the crash had freed money to seek other investments.

At right, President Herbert Hoover. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

At right, President Herbert Hoover. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

The newspaper became ambivalent, shouting on the same page:

"Stocks hit lowest levels in 16,410,030-sales day!" and "Wall Street recovery is started."

Gazing across his office at an autographed photo of President Herbert Hoover, Blethen tried to

calm local investors. Over the following weeks, he called for reassuring words first

from bankers and brokers, then from industrialists and university professors, and finally

from rabbis, priests and ministers.

Factory orders and construction projects stopped. Banks

that had speculated in the market closed, broke and unable to pay their depositors.

For ordinary Americans, the 1920s go-go economy was replaced by chronic unemployment.

Where 10 state workers had stood in 1929, six remained in 1932 -- you couldn't buy a job.

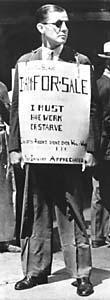

As the shockwaves of the Great Crash spread across the country, national wire services provided member newspapers with

photos of the newly down-and-out. Left, Robley Stevens stands on a Baltimore streetcorner, declaring he

"must have work or starve," and advertising his availability to "the highest bidder."

As the shockwaves of the Great Crash spread across the country, national wire services provided member newspapers with

photos of the newly down-and-out. Left, Robley Stevens stands on a Baltimore streetcorner, declaring he

"must have work or starve," and advertising his availability to "the highest bidder."

Photo Credit: Associated Press.

Hoover steadfastly maintained that federal intervention in the economy was unwarranted.

His cheery messages -- that better times were just around the corner -- became standing jokes. Hoover's

name was immortalized by those great parodies of hope, the Hooverville shantytowns that sprang up from Newark

to Seattle.

Up and down the railroad line, throughout the United States and into King County,

hobos rode the rails.

In Renton, a kind-hearted woman knew that the hobos had marked her gate with some sign

indicating she was a soft touch for food. But she didn't really mind. Times were hard, she said,

and men were ashamed. You could see it in their eyes when they asked what they could do to earn their meal.

On a little farm, there was always kindling to split or weeds to pull. Something to do.

For many rural Times readers, there had been no great 1920s boom, no "Puttin' on the Ritz"

in tennis whites or evening dress. Prices for timber and farm products had remained low throughout the decade.

In country towns, folks continued to stitch a living together as they always had -- dig some ditches for the county,

put in a kitchen garden, raise a pig, work an occasional month at the mill. They had some land; they were lucky.

Homeless families camped in abandoned chicken sheds and barns. Before the New Deal,

face-to-face charity through churches and clubs provided most of the relief offered in Washington state.

In Kirkland, fund-raisers held a Depression Ball in the high-school gym.

King County set aside $2,500 each month for unemployment relief in the Kirkland area alone,

providing one day's road work each week for 100 men in strict rotation, according to need. The county's

Willows Farm in Woodinville -- widely known as the "Lazy Husband Farm" -- housed men whose principal

crime was alcoholism, poverty or mental illness. The men distributed milk and vegetables to the poor

while administrators hoped that the work would somehow redeem these men.

In the summer of 1929, the United States had seemed a capitalist's dream -- dynamic,

inventive, thrilling. In 1931, the nation seemed a post-industrial failure -- hungry, sullen and out of work,

shuffling through a city soup kitchen or gone to ground, back to Grandma's house, to scratch out a

living on the land.

Crackbrained theorists and hatemongers commanded huge weekly radio audiences;

street-corner radicals called for revolution. Who was to blame? What would happen next?

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities

and do research, writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.