This story ran in The Seattle Times on March 17, 1996

By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

In this desolate 1910 scene

looking south from Bell Street across Fourth Avenue,

few of what were jokingly referred to as "spite mounds" remain of what was once Denny Hill.

Photo Credit: Asahel Curtis / UW Special Collections

SEATTLE HAD BIG DREAMS.The famed Seattle Spirit provided the money,

muscle and moxie for the city's remarkable transformation from boomtown to metropolis;

it also encouraged dreamers -- mostly visionaries and a few schemers -- who had even grander

ideas for the future.

From building skyscrapers to drilling tunnels, cutting away hillsides

or bridging the lakes, their great notions soon changed the entire cityscape.

Seattle was not alone in its ambitions, as colossal engineering projects

like the Panama Canal gave the world notice of America's tremendous technological capabilities and

"can do" spirit. But on a regional scale, the city's projects were equally grandiose,

if not occasionally outrageous.

Why not dig a ship canal from Elliott Bay to Lake Washington,

fill in the lower half of Lake Union for more industrial space or build a giant

commuter tunnel under First Hill? And while we're at it, why not even get rid of all

those hills blocking the city's growth?

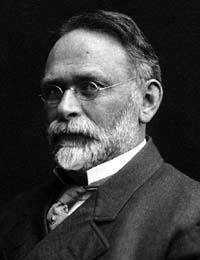

As taxpayers and politicians fought over how much it would cost,

planners and builders forged ahead to redesign the city. Leading the way was R.H.

Thomson, the intense city engineer who oversaw all municipal construction --

from sewers and sidewalks to bridges and public buildings. A technical man with a streak of

imagination, he let no natural obstacle stand in the way of completing

the infrastructure of a great city.

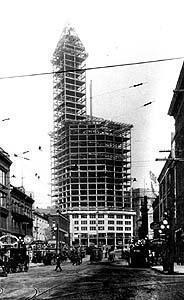

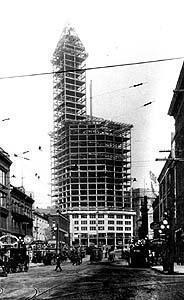

1911. Construction

of L.C. Smith's 42-story tower at Second Avenue and

Yesler Way begins after the City Council lifts height restrictions.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times

TENACIOUS AND INFLEXIBLE, HIS DISDAIN for those who did not share

his vision also made him many enemies.

Thomson's work had always generated controversy.

Back when Seattle needed a reliable water supply, Thomson had advocated and

successfully carried out an ambitious plan to run a pipeline nearly 30 miles

from the Cedar River. His insistence on municipal ownership of this water system,

as well as lighting and power plants, pitted Thomson against businessmen

who wanted private development rights.

But none of his proposals generated more debate than regrading,

the dramatic sculpting of Seattle's hillsides to make the march of progress much less steep.

Earlier regrade projects had leveled First Avenue, filled in parts of Westlake

and excavated sections of more than 28 other downtown streets. But the greatest obstacle

to the city's northward growth was Denny Hill; here Thomson's engineering know-how was put to the test.

Between Pioneer Square and Lenora Street -- a distance of about 12 blocks --

Second Avenue climbed 190 feet, too precipitous for most traffic. And perched atop the hill

was the huge Washington Hotel, a city landmark whose owner, James Moore, initially opposed Thomson's plans.

But the attractions of easier commercial growth and crosstown access persuaded

the city to level Denny Hill. When steam shovels couldn't do the job, huge hydraulic

pumps were brought in. Pointing gigantic water cannons at the hillside,

Thomson's men sluiced nearly 6 million cubic yards of earth into tunnels and

flumes that then dumped it into Elliott Bay.

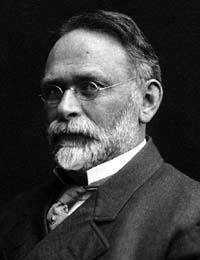

1908. City Engineer

R.H. Thomson, left, develops the city's infrastructure by building the North Trunk

sewer line and a second Cedar River pipeline.

Photo Credit: Edward Curtis, Rainier Club Coll.

THE MUD AND DISORDER SEEMED ENDLESS. Some applauded Thomson's untiring efforts,

while others, such as The Times, loudly accused him of despotism, even graft. Some property owners

sued to stop the work, but found their homes or businesses left on pinnacles of earth as

the regrading proceeded around them. Even James Moore eventually conceded, and 141 feet were

excavated from his hotel's site; he rebuilt on reconstructed Second Avenue.

By 1910 this phase of the Denny regrade was nearly complete, halting at

Fifth Avenue. Excavation of the eastern half of the hill did not resume until 1929,

although other major thoroughfares, including Jackson and Denny, were totally

transformed between 1907 and 1912.

Once an area was regraded, development could proceed. Competition arose

between regrade entrepreneurs and landowners in the original city center to the south.

An Eastern investor, L.C. Smith, began construction of Seattle's first true skyscraper,

the 42-story Smith Tower, in 1911, revitalizing the Pioneer Square area.

But in that same year citizens were presented with an elaborate proposal

to redesign the entire city, including a new civic and transportation center in the heart

of the Denny regrade.

Developed by noted engineer Virgil Bogue and strongly supported by Thomson,

the Bogue Plan was bold, sweeping and farsighted. As they had during the regrade efforts,

backers assumed that nature should be subdued, no matter what the cost and disruption.

Most Seattle residents, however, were tired of the mess and unwilling to pay the price.

Voters defeated the Bogue Plan in 1912, leaving Seattle to develop slowly, in a more piecemeal

fashion than its overeager planners had dreamed.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities

and do research, writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.

More photos

Table Topics

Copyright © 1996 The Seattle Times Company