By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

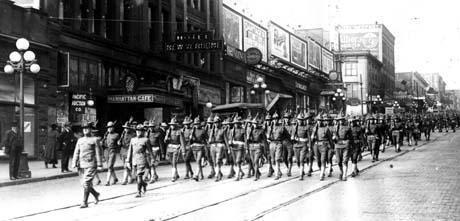

In the fall of 1917, the Second Washington Infantry's Seattle Battalion

paraded down First Avenue to encourage participation in the government's

Liberty Loan bond drive, raising money for the war effort.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

THE UNITED STATES ENTERED WORLD WAR I IN APRIL 1917,

nearly three years after hostilities broke out between the Central and Allied powers in Europe.

German U-boat warfare had raged against British and neutral shipping while

the Kaiser's armies struck overland against Belgium, France and Russia. Alliances pulled world powers

into the fighting one by one as the war spread from Europe to Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

In France, the opponents threw everything they had at one another until their armies ground

to a halt, digging in for years of trench warfare on the western front.

The war's images were shocking. Every day, the city's papers ran photographs of

the devastated fields and towns of France, the long columns of Russian refugees shuffling through

the snow, the packs of hungry orphans begging in Belgium. War correspondents and photographers

risked their lives to report the military stalemate for Seattle readers.

The papers brought home the grinding exhaustion and boredom of the muddy trenches

and the breathless rage and terror of combat.

After registration, Seattle's first draftees were chosen by lot

in the fall of 1917. The Seattle Times' editor-in-chief, C.B. Blethen, commandant

of the state's National Guard, had long preached the gospel of preparedness

on the paper's editorial pages. But as the American Expeditionary Force

trained to enter the war in Europe, The Times worried that American soldiers were poorly prepared.

Seattle newspapers featured daily photographs of

the horror and the boredom of warfare. At right, American soldiers in France tried to doze

in their trench as snow dusted the ground in 1918.

Seattle newspapers featured daily photographs of

the horror and the boredom of warfare. At right, American soldiers in France tried to doze

in their trench as snow dusted the ground in 1918.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times

THE NEWSPAPER FEATURED COVERAGE OF EVERYDAY LIFE ON THE FRONT,

showing men smoking or playing pinochle. But American soldiers also suffered the

common miseries of trench-foot and trench-itch, of fever, diarrhea and tuberculosis;

they sustained horrible shrapnel wounds, they were gassed, and they entered the private

hell of shell shock. The newspaper didn't flinch from publishing photos of young men

in wicker-basket litters coming home to military hospitals.

When local boys went off to join Allied troops on the battlefront,

Seattle became just another city on the American homefront. Like everywhere else,

the city's German Americans found themselves under suspicion as spies

for the Kaiser's war machine. Washington banned the teaching of the German

language in high schools, and Seattle music-lovers gave up Wagner.

Like all Americans, Seattleites did without whiskey and beer,

and tightened their belts on Wheatless Mondays and Meatless Tuesdays.

They were urged, reminded, then badgered to finance the war by buying Liberty Bonds.

The state's industries mobilized to fight the war. Tough, light spruce

was in demand for many military uses, including the biplanes at William Boeing's fledgling company.

But in 1917, the labor movement's Wobblies were leading a paralyzing strike in the woods,

fighting dreadful working conditions.

The Times ran slogans such as "To Hell with the Kaiser" as space fillers

in both its news and advertising columns throughout the war.

WASHINGTON'S FORESTS WERE ESSENTIALLY NATIONALIZED for the duration,

and soldiers cut the timber crucial for war. Puget Sound shipyards built battleships,

transports and ships of every description, employing nearly 40,000 people in Seattle alone.

As war news broke, seattle's dailies printed extra editions and newsboys fanned

through the city to yell, "WUXTRA! WUXTRA! Yanks Gain at St. Mihiel!" In these years before radio,

the great plaza before The Seattle Times Building became the city's gathering place.

An elaborate code of whistle blasts brought people to Times Square on the run,

anticipating the news of a victory, a defeat or peace.

In the fall of 1918, an influenza epidemic swept the United States,

claiming 10 times the casualties of the battlefield. In Seattle, schools and theaters

were closed for more than five weeks as health authorities tried to quell the outbreak,

spread by G.I.s returning to Camp Lewis. Cautious people were afraid to leave their homes,

and joy at the war's end was muted by fear of crowds and disease.

World War I ended in November 1918, and the Pacific Northwest took stock.

Three million Allied soldiers had died -- nearly 800 from Washington state.

President Woodrow Wilson had posed the war to Americans as a moral

quest to make the world safe for democracy. But in Washington state, the war had claimed precious

lives, trampled civility and freedom, and disrupted the economy. There would be many reckonings.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities

and do research, writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.