By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

In the 1930s, Florence and Burton James, former drama teachers at the Cornish School,

founded the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, now part of the UW.

Photo Credit: Special Colls., UW Libraries.

SEEKING DIVERSIONS FROM THE DEPRESSION BLUES, local folks crowded into vaudeville shows,

movies and concerts by crooners like Nelson Eddy. But they also had access to an array of

"high culture" -- from Shakespeare to chamber music to La Boheme. Local arts organizations

and promoters, aided by a few philanthropists and federal work programs, helped sustain --

even expand -- Seattle's artistic community during the lean years of the 1930s.

The Fine Arts Society, the Ladies Musical Club and the Civic

Opera Association were only some of the civic groups sponsoring concerts or organizing

benefits for arts scholarships. The handful of prominent families whose fortunes remained

intact put up large donations for major facilities. Richard Fuller and his mother, Margaret,

gave the Seattle Art Museum building to the city. The Volunteer Park landmark was completed in

1933. And impresario Cecilia Schulz, who took over management of the Moore Theater two years later,

successfully promoted events as varied as Rachmaninoff concerts and performances by the Ballet Russe.

The Cornish Trio, at right, featured some of the school's most respected faculty members:

Kolia Levienne on the cello, Peter Meremblum, violin, and Berthe Poncy at the piano.

Photo Credit: Special Colls., UW Libraries

At the core of the region's cultural scene was the Cornish School,

founded by "Miss Aunt Nellie" Cornish, who began as a popular piano teacher but had bigger

dreams of expanding artistic opportunities in the region. Starting with two rooms in a Broadway-area

hall during the World War I years, she proceeded to establish a full-scale arts institute with its

own Moorish-style campus. By the early 1930s, Cornish had gained an international reputation, drawing

faculty and students from all over the world.

Dance, music, drama, sculpture and painting -- all were part of the Cornish curriculum.

The school preached the interdependence of the arts, a philosophy that permeated the cultural community

of the city. Many of Seattle's leading artistic lights had some connection to Cornish, and formed a tight

network of support for each other.

In the 1930s, Florence and Burton James, former drama teachers at the Cornish School,

founded the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, top, now part of the UW.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

In the theater, for example, it was Florence and Burton James, who had first been

hired to run the Cornish drama department in 1923. After five years the couple founded their own company,

the Seattle Repertory Playhouse, using former Cornish students as their principal actors. Independent and

at times controversial, focusing more on literary drama and avant-garde pieces than popular escapist comedy,

the Jameses gained enough community support to build their own theater in the University District, opening

in 1930 with George Bernard Shaw's "Major Barbara."

The Playhouse's existence was precarious throughout the Depression --

more than once the electricity was cut off for nonpayment -- but theater parties

for Seattle's elite kept the doors open. The Jameses also received some funding

from the New Deal's Federal Theater Project, helping establish the innovative Negro

Repertory Theater which cast more than 50 of the city's black actors in major roles.

At right, "Is Zat So,"was sponsored by the New Deal's Federal Theater Project.

Photo Credit:Cornish Collection, Special Colls., UW Libraries.

A frequent playgoer and also designer of the theatrical masks at the Playhouse entrance was painter Mark Tobey.

Young and still struggling when asked by Nellie Cornish to join the faculty, Tobey soon found his career

accelerating when three of his paintings were chosen for a 1931 Museum of Modern Art exhibition in New York.

One-man shows at both the Cornish School and the newly built Seattle Art Museum helped introduce local

residents to the "modernism" that was rapidly gaining Tobey national acclaim.

Tobey spent much of the Depression in England but returned

to Seattle in 1938 and for a short time joined the Federal Arts Project,

sponsored by the New Deal's Works Progress Administration. Tobey and several of his

fellow "starving artists" on the project -- including Morris Graves, Guy Anderson, Fay Chong

and William Cumming -- formed the heart of what soon came to be referred to in artistic circles

as the Northwest school.

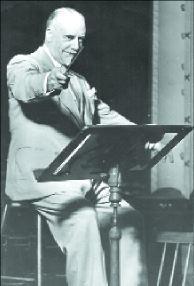

Sir Thomas Beecham,

the outspoken conductor of the Seattle Symphony from 1941 to 1943, poked fun at Seattle audiences

and constantly battled local critics, calling them "illiterate, incompetent, unmusical."

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

Seattleites did not always appreciate the rich artistic ferment

of these Depression years. The Cornish School's ambitious productions were often poorly attended,

and constant battles with the board of directors over financing caused Nellie Cornish herself

to leave the city in 1939.

A Repertory Playhouse production of Clifford Odets' "Waiting for Lefty,"

highly sympathetic to labor radicalism, caused such a furor that The Times banned the company,

refusing to advertise, review or even mention the Jameses' plays for many years.

And while a few art patrons bought the works of Tobey, Kenneth Callahan and other

Northwest School painters, local critics often panned their efforts. One Seattle reporter compared

Tobey's prize-winning entry in the 1940 Annual Exhibit of Northwest Artists to something the second

grade at Magnolia School might have dreamed up, and two of the city's papers (not The Times)

ran a photograph of the painting upside down.

The flamboyant and frequently acidic director of the Seattle Symphony, Sir

Thomas Beecham, who came to the city in 1941, had his own run-ins with press critics.

In his most famous diatribe, he expressed disdain for Seattle's artistic pretensions, calling the city

"an esthetic dustbin." But Beecham underestimated the city's spirit. Despite the hardships of the

Depression and its own conservatism, Seattle had produced world-class artists and the infrastructure

for a thriving cultural community.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of the Seattle Public Library.