By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

A General

Electric Co. employee held a portable radiation detector

at Hanford to trace radioactivity in the plant's "hot zones."

Until the U.S. bombed Hiroshima, most of the 17,000 workers did not know they were producing plutonium.

Photo Credit: General Electric Company.

THE MYSTERY WAS OVER.

With President Harry Truman's Aug. 6, 1945, announcement

of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, the world discovered the reason

for the secrecy surrounding the Hanford Engineering Works in south-central Washington.

Most of the 17,000 workers at the huge government complex on the Columbia River also

learned for the first time that they were manufacturing plutonium -- a key ingredient

in making bombs more powerful than 20,000 tons of TNT.

Like proud parents, residents of the federally built city of Richland

marveled at their role in the creation of a weapon that could bring a quick end to war with Japan.

"It's Atomic Bombs," a banner headline in the local paper proclaimed. But there were also worries

that this "most-terrible destructive force" could be used for evil as well as good. Few could conceive

of what the long-term fallout from Hanford might be.

Despite Japan's formal surrender in September 1945, the work at Hanford continued

round the clock. Plutonium, according to one Seattle Times reporter, became "the hottest item in the Cold War."

Although President Truman had vowed to make atomic energy "a powerful influence toward the maintenance of world

peace," the rapid deterioration of relations with the Soviet Union instead made it the force behind a

frightening game of one-upmanship.

Americans were stunned by the news that the Soviets had exploded their own atomic weapon

in September 1949. And although the government downplayed the danger to national security,

Nobel Prize-winning scientist Harold Urey summed up popular thinking: "There's only one thing worse

than one nation having the atomic bomb," he commented. "That's two nations having it."

The risk of atomic war grew and with it calls for new, more elaborate defensive

strategies. The Northwest was seen as a likely bombing target, not only because of its

geographic proximity to potential enemies, but also because it was the home of Hanford and other

important defense industries as well as several large military bases.

The need for preparedness at home was emphasized in the "alert America" exhibit

which toured Seattle and 69 other cities in 1952.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

AREA RESIDENTS FOUND THEIR WORST FEARS CONFIRMED when the Air Force,

citing Seattle's

"relative vulnerability," announced plans to relocate its bomber production to a Boeing plant

in the Midwest. With both community safety and economic well-being at risk, business leaders

launched a huge emergency campaign: "Keep Boeing -- Defend Seattle." Fierce lobbying and political

pressure brought government promises to continue local production of military aircraft, including

the new B-52, and also to expand regional defense systems.

After tours of Hanford and Air Force control centers, U.S. Rep. Henry Jackson

assured his Washington constituents that radar screens and technologically superior

weaponry protected them from enemy attack. But Northwest families, with new homes,

new babies and new postwar dreams, still felt their security threatened.

Communities large and small organized civil-defense units, purchasing state-of-the art sirens

and emergency equipment and staging mock blackouts to test evacuation procedures. King County officials

mapped the estimated fallout area if a thermonuclear device were dropped on Seattle, marked escape routes

and circulated "red alert" instructions to residents. "Operation Skywatch" volunteers scanned for

low-flying aircraft 24 hours a day from posts atop mountains and tall buildings.

Even businesses saw a need for preparedness, holding their own air-raid drills and

issuing civil-defense ID tags to employees.

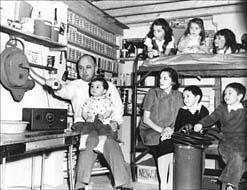

Many got the message, including the Lee E. Sinclair family, whose well-equipped basement fallout shelter was built with the assistance of the Seattle-King County Civil Defense Agency. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

BUT IT WAS THE CHILDREN WHO MOST DESERVED PROTECTION, and worried parents worked

to make homes and schools safer in case of atomic attack. Government pamphlets distributed to

teachers provided tips on survival techniques. Students from Montlake Elementary to Franklin High

School learned the drill: Close the shades, lie down flat in a shielded spot, and above all, don't panic.

Families were urged to keep special emergency rations to last a minimum of three days.

Side by side with articles on Dr. Spock's tips for child-rearing, local newspapers ran instructions for

do-it-yourself bomb shelters. And for those who weren't handy, a Seattle company manufactured a reinforced

concrete model retailing for only $595.

Despite the dangers, the postwar baby boom continued unabated. From suburban housing

tracts to shopping malls, new development was aimed at "Mr. and Mrs. Seattle" and their children.

The Northwest, home of Hanford and the bomb, was also home to the nuclear family.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of Seattle Public Library.