By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

At right, these boys seemed ready for mischief around the turn of the century when this photograph was taken,

but later in life they were solid citizens. The third young man from the bottom, Du Bois Mitchell,

became the librarian of the University of Puerto Rico, while MacBurney Mitchell,

clinging to the top of the pole, headed the German department at Brown University. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

At right, these boys seemed ready for mischief around the turn of the century when this photograph was taken,

but later in life they were solid citizens. The third young man from the bottom, Du Bois Mitchell,

became the librarian of the University of Puerto Rico, while MacBurney Mitchell,

clinging to the top of the pole, headed the German department at Brown University. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

AS SEATTLE PROSPERED, MANY RESIDENTS HOPED

THE CITY WOULD ABANDON ITS BOOMTOWN LIFESTYLE and become a family town.

The children of the rapidly expanding middle class grew up with the city

and led a more pampered, protected existence than previous generations.

Their progressive parents gave them more attention and respect, but

also insisted on solid moral instruction and strict control over their activities.

City institutions also helped shape children's lives, providing better educational

opportunities and new public places for them to have fun.

Parents in the early 1900s wanted to give their offspring the best,

and local businessmen stood ready to oblige. Daily newspapers were full of advertisements

for children's products -- everything from cold medicine to comfortable carriages and intriguing toys.

Department stores carried a full selection of children's clothing, including silk party frocks for

"little women in miniature" and "manly little suits for boys." If mother and father wanted to pay the price,

they could even outfit their tikes in the latest Paris fashions.

At left, new public and private schools built after the turn of the century

provided the region's growing student population with a "modern" education. In about 1906, young women

at the former St. Rose's Academy were learning the basics of physics. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

At left, new public and private schools built after the turn of the century

provided the region's growing student population with a "modern" education. In about 1906, young women

at the former St. Rose's Academy were learning the basics of physics. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

THE WELL-BRED CHILD AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY ALSO might learn to dance at

a local academy, paint with a master, or take music lessons from Nellie Cornish,

who later established Seattle's pioneering school for the arts.

Local newspapers soon began to run features devoted exclusively to the

interests of young people. In 1906, The Times inaugurated an eight-page weekly magazine supplement

for boys and girls, offering adventure stories, science projects, poems and puzzles.

Most of the children's fiction provided moral instruction -- work hard, be brave,

always share and never lie. The magazine also sponsored essay competitions

on topics like "What I Like to Read About," and "Industry Contests" offered prizes

for hard-working students who gathered the greatest number of newspaper coupons.

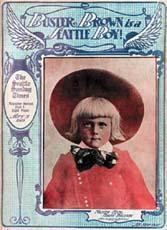

Even some of the Sunday comics carried reminders about proper behavior.

Among the most popular was the Buster Brown series, whose title character was a

lovable 10-year-old who frequently got into mischief but always learned important

lessons. Buster Brown became a national icon, the namesake for a line of clothes,

shoes and other products.

In 1905,

The Times declared Cecil Bullock of Ballard, right, a look-alike to the famed comic character Buster Brown.

Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

LOCAL BOOSTERS LIKED TO BRAG ABOUT THE SUPERIOR REPUTATION of the city's schools,

"a sure index of the character and substantiality of any community." After a few early growing pains,

the public-school system rapidly expanded to meet the needs of the burgeoning student population.

In 1903, more than 15,000 pupils enrolled, while 20 years earlier barely

1,000 had attended. During the next decade the School Board authorized construction

of 40 schools in developing family neighborhoods to provide the up-to-date settings parents demanded.

The city could not keep pace, however, with demand for new recreational areas.

Children flocked to Seattle's parks to enjoy sandboxes and wading pools, swings and teeter-totters.

The city hired supervisors to organize playground programs during summer months and teamed up

with the public library to encourage reading during park visits.

Not all Seattle young people had the free time to take music lessons or even

to play outdoors. Many local children worked in stores, factories or on surrounding

farms to support themselves or help out their families. And reformers failed to get

stricter laws to control these practices.

Seattle's newsboys were the most conspicuous young laborers,

hawking papers on streetcorners throughout the city. Some still resembled

the street urchins of 19th-century Horatio Alger novels -- homeless and exploited --

but many 1900s newsboys worked after school hours or attended night

classes through the public schools.

These entrepreneurs established a Newsboys' Union which protected their

rights to sell papers at designated spots, paid medical expenses if

they fell ill, and sponsored dances, picnics and other social functions.

As late as 1915, nearly 14 percent of all eighth-grade boys in the city sold papers on the streets.

Seattle had its share of delinquents involved in pranks,

robberies and assaults, but the city joined parents in trying to make childhood a

happy, productive time for most young people. Vice and crime, however,

continued to threaten their efforts to make Seattle truly a family town.