By Sharon Boswell

and Lorraine McConaghy

Special to The Times

Seattle began its 100th birthday celebration with a re-enactment of the Denny party landing,

complete with residents costumed as Settlers and Indians. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

Seattle began its 100th birthday celebration with a re-enactment of the Denny party landing,

complete with residents costumed as Settlers and Indians. Photo Credit: Seattle Times.

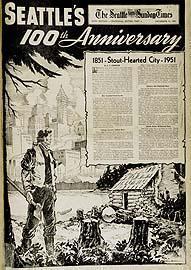

A TIME FOR SERIOUS REFLECTION AS WELL AS LIGHTHEARTED REMINISCING, a

centennial also offers a chance for a bit of justifiable self-promotion, myth-making and zany fun.

"With proper pride in the achievements of the past and with full confidence in its own destiny,"

Seattle began its yearlong centennial observance Nov. 13, 1951. Civic and business leaders had chosen

that date because it commemorated the arrival of the Denny party in 1851.

Never mind that others, Indian and white, had preceded Arthur Denny

and his small group of settlers to the region -- or that Seattle proper had grown

from a second site founded months later on the other side of Elliott Bay: Centennial

planners wanted a dramatic event to mark the city's birth.

Thousands attended the opening ceremonies as Seattleites in pioneer dress re-enacted

the landing on Alki Beach, arriving on a schooner meant to simulate the sailing vessel which

had brought the pioneers from Portland to rain-soaked Puget Sound. According to newspaper accounts,

"costumed and painted Indians" watched curiously from shore; the "Indians,"

members of the West Seattle Sportsmen's Club, then barbecued salmon for the throng.

A highlight of the event was the burial of a time capsule

representing life in 1951 Seattle.

The guest of honor for the city's centennial kickoff was General Douglas Macarthur,

still wildly popular in Seattle despite his well-publicized feud with President Harry Truman over

Korean War policy.

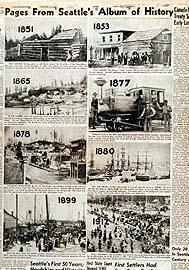

Newspapers provided extensive coverage of these festivities just as they had

documented much of the rest of Seattle's remarkable journey. A special section of The Seattle

Times offered numerous "Pages from Seattle's Album of History."

Headlines described the city as "Proud but Humble" at its 100-year milestone.

Local newspapers played an important role in documenting the city's growth from frontier outpost to thriving metropolis. The Times commemorated Seattle's centennial with a special edition, using photographs and stories to compile an album of civic history over 100 years.

THE PAPER WAS ALSO PROUD, IF NOT ALWAYS HUMBLE, about the role

it had played in reporting local history. The Times was not the city's oldest newspaper,

but it had provided coverage of significant people and events for more than half of Seattle's

first 100 years.

The Seattle Gazette is usually regarded as the city's first hometown paper.

With a population of scarcely more than 120, tiny, struggling Seattle in 1863 had only enough

news to fill four pages, published on an irregular basis.

Another decade passed before Seattle could support a daily paper lasting more than a few months.

In 1876, the Daily Intelligencer was born, combining with the Post in 1881 to become

the largest and most profitable newspaper in all of Washington territory.

Serious competition for the staid Post-Intelligencer did not emerge

until 1896, when Alden Blethen came to town. Broke and dispirited after a series of

financial failures, Blethen, at 50, still possessed a wealth of newspaper experience

which he used to turn the "decrepit little" Seattle Daily Times into a viable paper.

The Times, which traced its roots through a series of owners and mergers back to the

1881 Seattle Chronicle, was so close to bankruptcy that its only real asset was an Associated Press franchise.

Sensing an opportunity, Blethen borrowed enough to buy the paper and keep it running until

the Klondike gold rush provided the money and momentum to propel both Seattle and The Times into new prominence.

ALTHOUGH CONSTANTLY BATTLING FOR CIRCULATION WITH THE P-I and later competitors such as the Star and the Sun,

The Times established itself as the paper to beat. Alden Blethen had infused its pages with his

wn unmistakable personality -- belligerent, obstinate, often outrageous -- and kept readers

interested by combining sensationalism with the latest newspaper technology. His son,

Clarance, who followed him as editor, gradually turned away from his father's "personal journalism,"

but carried on his love of innovation, constantly updating facilities and experimenting with new equipment.

By Seattle's centennial in 1951, The Times had only recently passed into

the hands of a third generation of Blethens, who had grown up with the paper and the community.

Reflecting the surge which had boosted metropolitan Seattle's population to more than 725,000,

the daily circulation of the Times had increased by 111 percent since 1940. The younger

Blethens pushed for up-to-date color presses and an addition to the Fairview and John plant

to help the paper, in its own words, "keep up with the times."

But to keep up with Seattle of the 1950s required both a respect for the past and an eye

to the future. Neither the city or its newspapers could afford to rest on their achievements.

Suburban growth, new technology and a rapidly diversifying population required mature reflection

as well as youthful energy so that the next 100 years would truly be something to celebrate.

Historians Sharon Boswell and Lorraine McConaghy teach at local universities and do research,

writing and oral history. Original newspaper graphics courtesy of Seattle Public Library.