|

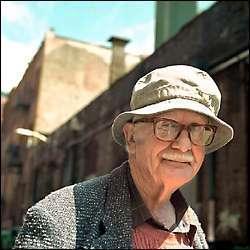

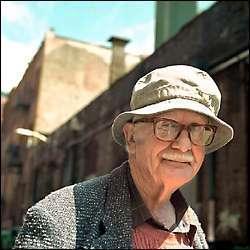

TOM REESE / THE SEATTLE TIMES

|

A LINK TO THE PAST

Remembering Seattle in the 1930s: Bill Cumming recalls flophouses and greasy-spoon cafes, a city where Communists put down roots and Wobblies shut down the town. |

Bill Cumming steps gingerly across the cobblestones of Occidental Park, pauses to steady himself beside a lamppost, and examines the streetscape at First Avenue and South Washington Street. Behind thick, horn-rimmed glasses and the floppy brim of his cap, 84-year-old eyes study images of brick and iron that trigger memories of a turbulent decade.

"Up there was the Trotskyite headquarters," he says, pointing to the top of the Maynard Building. "Up at the other end of the block was the Washington Pension Union, headed up by Bill Pennoch, and I suppose he was the best-known Communist in town."

A bit tottery without his cane, the venerable painter and teacher — last of the famous "Northwest School" of artists that included his friends Mark Tobey and Morris Graves — takes a few more steps down South Washington.

He points to where a charismatic preacher evangelized by day and reputedly "ran a string of girls" by night. He points to where he heard Charles Lindbergh speak to a huge crowd on his cross-country barnstorming tour in the "Spirit of St. Louis." He recalls the Skid Road flophouses and greasy-spoon cafes "where you could get a decent meal for 35 cents, unless you wanted pie."

Seattle in the 1930s occupied a damp, remote corner of a young, broad-shouldered nation. It was an adolescent city with 350,000 people and a colonial economy based on harvesting its trees and fish and Eastern Washington wheat and shipping them off to distant places. It had been just 80 years, one healthy lifetime, since the Denny Party landed at Alki Beach, and there were still Seattle residents who had known those pioneers.

"This was mostly a city of lumpy, dusty people — the people I paint," Cumming recalls. "It was a city of working stiffs trying to make a living. There was a wonderful small townness. Tree-lined streets and family homes. People sitting in the cabbage patch above Sicks' Stadium, watching minor-league baseball."

Today, as Seattle prepares to celebrate the 150th anniversary of its founding, the years of the Great Depression seem almost as distant as the Denny Party. But we all have neighbors who lived through and perhaps came of age during that troubled decade.

Their experiences were vastly different, but they share one observation: The 1930s was the last hurrah of "Old Seattle."

"The day after Pearl Harbor, there were sentries on station at Boeing," Cumming recalls. "The city would never be the same again."

Seattle would be changed profoundly by thousands of servicemen, plus welders and steelworkers and engineers from around the nation who came to build bombers and warships — and stayed here. It would be changed by megawatts of surplus hydropower from the new Grand Coulee Dam, by automobiles and Interstate highways, by television and a World's Fair. It would be changed by the Lake Washington floating bridge, which opened the Eastside to a suburban boom. Seattle's seniors recall this transformation with some nostalgia, but little regret. For most, life in the `30s was hard.

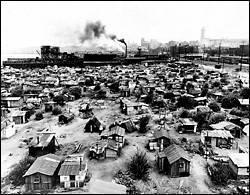

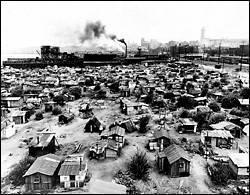

Like most cities, Seattle was clobbered by the stock-market crash in 1929. By late 1931, wages had fallen 35 percent and as many as 20,000 were out of work. Retail sales were off by 17 percent, construction down by 70 percent. The official unemployment rate was 7 percent, but the reality was far worse. Shipping and shipbuilding ground to a halt. Forty Northwest lumber mills closed. Hundreds of men lived in a shantytown known as "Hooverville," a few blocks south of Pioneer Square, where the unemployed picked their own mayor, enforced their own rules and tweaked the establishment.

|

| SEATTLE TIMES FILE PHOTO |

| In 1931, homeless men put up 50 scrap-lumber shacks in just two weeks on this tract south of downtown. For the next decade it was 'Hooverville,' named for President Herbert Hoover. |

The climate was ripe for radical politics. Seattle already was known across the country as a haven for left-wing politics — the Pacific Northwest "soviet" where, in 1919, the revolutionary Wobblies had led a citywide general strike.

"It was terrible," Cumming explains. "Good men felt guilty because they couldn't support their families. The system had failed. We all believed: There must be something better than this."

In his 84 years, Cumming has seen the best and the worst of his times. He was born in Montana, raised in Tukwila, where his father owned a share of a Chrysler dealership.

"The crash blew it all away," he says. "My father lost his business, and his partner took off with what was left. It took years for him to pay off the debts."

Cummings graduated in 1934 and headed for Seattle. Eventually, he landed a job with the Federal Art Project, where he met Morris Graves and Kenneth Callahan — already established Northwest artists. At age 21, Cumming was hooked by the world of art and artists, of social ideals and revolution.

For a time, he roamed the city, sketching. His favored subjects were at the State Burlesque on Skid Road, dockworkers and ditch-diggers, dancers and prostitutes. "I made $66 a month. Carpenters made $96, which gives you an idea where art sat on the federal totem pole."

Seattle was highly class-conscious, quietly racist, a city "ruled by a bunch of real-estate people," he says.

"Eventually, I became a Red. ... We were naïve. We talked about things we knew nothing about, and we believed it. So, when the Revolution turned into an outburst of murder, I went through the usual disillusionment."

Today, Cumming lives with his wife in a modest home with beamed ceilings and Persian carpets on oak floors, tucked into the woods in Lake Forest Park. He teaches painting three days a week at the Art Institute of Seattle and has staged a remarkable comeback as one of Seattle's best-known painters.

And he still paints several hours a day in a small studio, surrounded by his work — canvas rectangles painted in wandering lines and deep oranges and yellows, warm silhouettes of the lumpy people who populated a time and place that have long since faded away.

Ross Anderson can be reached at 206-464-2061 or randerson@seattletimes.com

|

Sunday, July 29, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific

Sunday, July 29, 2001 - 12:00 a.m. Pacific