Originally published May 13, 2014 at 10:40 PM | Page modified June 7, 2014 at 2:02 PM

Landslide risk keeps popular campground closed

TIMES WATCHDOG: Gold Basin Campground won’t open this year until a landslide-safety review can be conducted, a decision that follows a Times report on the area’s risks.

Seattle Times staff reporter

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

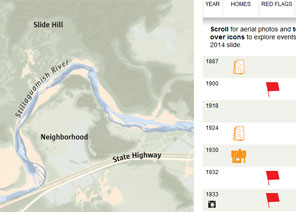

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

The U.S. Forest Service said Tuesday it has delayed the opening of a popular campground in Snohomish County until officials can conduct a landslide-safety review.

Peter Forbes, the Forest Service’s district ranger in Darrington, said in a statement that the agency wants to take a close look at the unstable slope that sits directly north of Gold Basin Campground.

A Seattle Times story last week described how the hill has similarities to the slope near Oso that gave way in March.

“Opening the campground will be delayed until the safety evaluation is complete,” Forbes said.

The Gold Basin hill has a lengthy history of landslides, and scientists reviewing the area have at times recommended shuttering all or part of the campground for good. Tracy Drury, an environmental engineer hired by the Stillaguamish Tribe, wrote in a 2001 report that slides on the hill “can be enormous in size,” with run-out distances approaching half a mile.

“If this occurred when the campground is heavily occupied, the potential for loss of life and property would be high,” Drury wrote. The facility can host more than 800 campers at a time.

Despite the history of warnings, the Forest Service had balked at suggestions that the campground be relocated or closed. Forbes previously noted that the agency has invested heavily in the campground’s facilities — which include an amphitheater, playfield and half-mile boardwalk — and that the site’s popularity translates into revenue for the federal government.

Forbes said last week that he hadn’t seen a compelling reason to justify getting rid of the campground.

The campground is typically open for visitors from about mid-May to mid-September, avoiding the peak rainfall season. However, slides have also occurred in Washington state in summer months, and a June 1996 slide extended into a portion of Gold Basin Campground, according to a 2012 report produced for the Stillaguamish Tribe. The Gold Basin hill is located on the Mountain Loop Highway near Verlot, and is about 15 miles away from the Steelhead Haven slope.

Gold Basin rises about 700 feet from the valley floor, about 50 feet higher than the Steelhead Haven slope that collapsed March 22, killing more than 40 people. Both of the unstable slopes are on the north side of a river, and landslides from the hills have at times pushed the river southward toward areas where people gather — a neighborhood in the case of Steelhead Haven, campers in the case of Gold Basin.

State records show that the idea of closing all or part of Gold Basin Campground has surfaced in reports from 1954, 2001 and 2012.

Because the Forest Service earlier had opposed the idea of closing the campground, the Stillaguamish Tribe was pursuing the construction of a log barrier — called a crib wall — along the base of the unstable hill. The wall would be similar to one the tribe built at the Steelhead Haven hill, with the goal of reducing sediment that can harm salmon habitat.

The alternative has been under consideration by the Forest Service and others. It isn’t meant to keep slides from occurring.

Mike Baker: 206-464-2729 or mbaker@seattletimes.com.

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!