Originally published May 7, 2014 at 9:09 PM | Page modified June 7, 2014 at 2:02 PM

Feds keep popular campground open despite risk of devastating landslide

TIMES WATCHDOG: Gold Basin Campground, the largest in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, is at risk of a devastating landslide, sitting at the base of a hill with eerie similarities to the one near Oso that collapsed in March in the same river basin.

Seattle Times staff reporters

Mark Harrison / The Seattle Times

The big Gold Basin Campground sits off the Mountain Loop Highway east of Granite Falls. The South Fork of the Stillaguamish River runs between it and a hill with a long history of landslides. The campground, owned by the U.S. Forest Service, opens for the season this week.

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

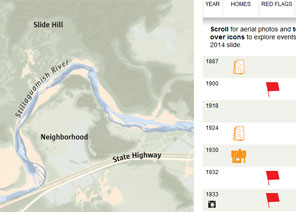

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

Gold Basin Campground is the largest in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, able to hold more than 800 campers on grounds that include an amphitheater, playfield, salmon-fry viewing area and half-mile boardwalk.

The campground — scheduled to open for the season Thursday — is also at risk of a devastating landslide, sitting at the base of a hill with eerie similarities to the Steelhead Haven slope that collapsed in March, about 15 miles away.

Slides have been documented at Gold Basin hill going back to the 1940s. Since 1954 there have been proposals to either move or close Gold Basin Campground, including one in the last few years to eliminate a portion of the site closest to the river, according to records obtained by The Seattle Times. But the U.S. Forest Service, which owns the campground and the surrounding land, has refused to go along.

“Because this campground is too popular,” a manager with the state’s Recreation and Conservation Office wrote in an internal email last month, about two weeks after the mudslide at Steelhead Haven.

The Forest Service has been part of a group studying the hill. The agency’s reluctance to close all or part of the campground, wedged between the Mountain Loop Highway and the South Fork of the Stillaguamish River in Snohomish County, has prompted a recent proposal to build a long wall of logs at the base of the landslide-prone hill.

A similar barrier — designed mostly to protect fish habitat by keeping sediment out of spawning grounds — was built at Steelhead Haven in 2006, only to be destroyed eight years later by waves of mud that swept across the river and killed more than 40 people on the other side.

“It would be so great to apply a lesson from this Steelhead Haven project to promote a river restoration project that would be better for fish and for people,” wrote Elizabeth Butler, a grants manager at Recreation and Conservation, which has helped fund research on possible ways to protect salmon from the slides on Gold Basin hill.

“Any way we can parlay this tragedy into a win for the south fork?” Butler wrote in her email to office colleagues. “[H]ope springs eternal for working smarter as we learn from past experience.”

Peter Forbes, the Forest Service’s district ranger in Darrington, said in an interview that the agency has invested heavily in the campground’s facilities and doesn’t have a good site for relocation. The campground’s popularity translates into revenue for the federal treasury, contributing to the government’s desire to keep the site, he said.

“I haven’t seen a compelling reason, I guess, to justify getting rid of the campground,” Forbes said.

The campground is the most popular in the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest and brings in the most money, state records say. The Times asked Forbes how much the campground takes in, but he was unable to provide figures by Wednesday.

A feasibility study generated by the Forest Service concluded it would cost about $3.5 million to rebuild the Gold Basin Campground somewhere else, records show.

The campground is usually open between mid-May and mid-September.

“Catastrophic failure”

For decades, the Stillaguamish Tribe has tried to find ways to protect the South Fork’s chinook salmon, whose numbers in recent years have dipped to about 100, sparking fears of extinction. The tribe has worked with a variety of agencies — county, state and federal — on proposals to reduce sediment flow from Gold Basin, a hill that has sent “hundreds of thousands of tons of glacial lake deposits downstream,” according to state documents.

A 2001 report prepared for the tribe offered five alternatives, including one to move the river away from the hill. That alternative would have rerouted the channel through the campground, requiring that the camping sites be abandoned or moved. The Forest Service balked, according to state records.

“The biggest hurdle to implementing this project over the past two decades has been the reluctance of the [Forest Service] to entertain any discussion of potential impacts to the campground across the river,” one report filed with the state says.

Although proposals from the tribe have been designed with salmon in mind, some reports on Gold Basin have also touched upon the threat to campers.

Tracy Drury, an environmental engineer hired by the Stillaguamish Tribe, wrote in the 2001 report that slides on the hill “can be enormous in size,” with runout distances approaching half a mile. “The effects of such an event could be catastrophic in terms of loss of human life and property,” he wrote. “If this occurred when the campground is heavily occupied, the potential for loss of life and property would be high.”

Drury used almost identical language — “catastrophic failure,” posing “significant risk to human lives and private property” — when he wrote about Steelhead Haven in 2000, 14 years before that hill fell away in one of Washington state’s worst natural disasters.

Snohomish County, in a 2004 flood-hazard management plan, also cited “significant concern of human life and property loss” at Gold Basin because of the campground’s proximity to the hill, where “massive slope failures have occurred over the years.”

Pat Stevenson, the environmental manager for the Stillaguamish Tribe, told The Seattle Times: “If it wants to come down in a big way, you wouldn’t want to be camping there.”

Similar slopes

The Steelhead Haven and Gold Basin slopes resemble each other in a number of ways. Both have a documented history of slides going back more than 70 years, according to reports from scientists. From the valley floor, the Steelhead Haven slope rises about 650 feet; at Gold Basin, it’s about 700 feet.

The two slopes have, or had, comparable configurations — hill, then river, then people (residents in the case of Steelhead Haven, campers in the case of Gold Basin), then highway. Highway 530 was about 1,600 feet from the bottom of Steelhead Haven. The Mountain Loop Highway is about 1,300 feet from the bottom of Gold Basin.

In the case of both hills, at least one landslide has pushed the river channel south, toward the people. That happened in 2006 at Steelhead Haven, and in the mid- and late 1990s at Gold Basin, according to scientific records.

But geologists say the two slopes differ in how the landslides are triggered.

At Steelhead Haven, geologists cited several factors that could contribute to slides; one was erosion at the hill’s base, caused by the river. That provided an opportunity to reduce the risk of future slides, if an effective buffer could be built between hill and river, or if the river could be moved away.

At Gold Basin, landslides don’t appear to be connected to the river cutting at the hill’s base, according to geological reports. Instead, rainfall appears to be the main trigger, with “a correlation between increased landslide activity and storms.”

So while a barrier at the hill’s base might help fish by blocking sediment, it would do little or nothing to prevent a major slide, according to scientific reports.

“There are no obvious means to stabilize the Gold Basin landslide,” wrote Dan Miller, a geologist, in a 1999 report for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that also included research on Steelhead Haven.

Experts say the active landslide area on Gold Basin hill consists of about 140 acres, split into three lobes that act independently of one another.

The possibility of closing all or part of Gold Basin Campground in order to move the river away from the hill has been brought up in reports generated in 1954, 2001 and 2012, according to state records. The 2012 report, produced by Drury for the Stillaguamish Tribe, named that as the “preferred alternative,” saying it was the option most likely to limit sediment going into the river.

But “based on feedback and correspondence” with the Forest Service, that option was off the table, Drury wrote, because of the “recreational and economic loss” that would cause.

So Drury’s report instead recommended building a log barrier called a crib wall, along with adding vegetation and a series of sediment basins. This alternative — under consideration by the Forest Service and others — would minimize sediment but do nothing to keep slides from happening, his report says.

Forbes, the district ranger, said that since the site is only open from May to September, campers aren’t there during the wetter winter months when slides typically occur.

About 75 percent of the area’s rain falls between November and March, according to one environmental report.

But around the state, heavy rains have frequently prompted slides in late spring and summer, causing road closures in September 2013, July 2012 and June 2011, among other periods.

And at Gold Basin hill, a landslide in June 1996 “extended into a portion of the campground,” according to a 2012 report produced for the Stillaguamish Tribe. The Times asked Forbes about that slide, but he could provide no details.

Drury warned in his 2001 study that while storms occur more often in winter, “available data cannot rule out the possibility that significant debris flow failures could occur at any time.”

Given the scale of the landslide at Steelhead Haven, Forbes said he expects the Forest Service will have renewed discussions about the potential risks surrounding Gold Basin hill. The agency will also move ahead on assessing the latest Stillaguamish plan to build the crib wall without moving the river.

“At this point,” Forbes said, “there’s nothing that we’re aware of that changes the risk to people using the campground.”

Staff reporter Justin Mayo contributed to this report.

Ken Armstrong: karmstrong@seattletimes.com or 206-464-3730; Mike Baker: mbaker@seattletimes.com or 206-464-2729

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!