Originally published April 28, 2014 at 5:00 PM | Page modified April 28, 2014 at 5:42 PM

Will Oso tragedy revive stalled national landslide program?

Ten years ago, a panel of leading scientists called for a comprehensive national program to reduce the risk from landslides. But the plan was never funded.

Seattle Times science reporter

Oso landslide: Comprehensive coverage of the March 22 disaster and recovery

The Seattle Times

A collection of stories and visuals about the disaster, why it may have happened and the people it affected.

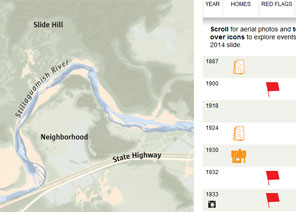

Interactive: Building toward disaster

THE SEATTLE TIMES

Use an interactive to see how, even as warnings mounted, homes kept being built in slide-prone Steelhead Haven.

Remembering the victims

Compiled by The Seattle Times

Read about the lives of the victims.

Interactive map: A detailed view of the neighborhood hit by the landslide

Garland Potts, Cheryl Phillips / The Seattle Times

Use an interactive tool to see the landslide’s deadly path.

TIMES WATCHDOG

![]()

Ten years ago, a panel of leading scientists called for a comprehensive, national program to reduce the risk from landslides — but the plan was never funded.

Now, experts are wondering whether the tragedy at Oso will revitalize efforts to assess landslide hazards, communicate them to the public and help local communities improve land-use planning.

“I think there’s a chance,” said Peter Lyttle, landslide-program coordinator for the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). “As in so many of these awful cases, it’s a teachable moment.”

But even the deaths of more than 40 people may not be enough to shift national priorities, said University of Washington political scientist Peter May, who served on the National Research Council (NRC) committee that authored the report in 2004.

“It might lead to innovative ways to use existing funds, but I don’t think it will lead to the creation of a serious, national program,” he said.

There has never been a groundswell of public support for efforts to lower the risk from landslides, May pointed out. And because slides strike sporadically and are usually isolated events, they rarely rise to the top of the list when politicians are drawing up budgets.

“It’s a difficult problem,” May said. “It’s only in the aftermath of events like Oso that alarm bells go off and people say, ‘Maybe we better do something about it.’ ”

The NRC committee recommended a $365 million, 10-year program coordinated by the USGS, with much of the money passed on to states. But actual funding for USGS’ landslide work has averaged less than a tenth of that amount over the past decade.

After several major landslides in the late 1990s, including one in La Conchita, Calif., that destroyed 14 houses, the USGS mapped out an ambitious landslide program at the direction of Congress. Based on data from the 1980s, the agency estimated 25 to 50 people are killed every year by landslides in the United States, with property damage exceeding $2 billion.

But those numbers are outdated, said Lynn Highland, of the USGS National Landslide Information Center.

Better measurement of the economic and human toll from landslides was one element of the program proposed by the USGS and endorsed by the science panel in 2004. Others included scientific research on landslides and their triggers, maps of high-hazard areas, and monitoring of the most treacherous areas to provide warnings for communities in harm’s way.

The plan also called for outreach programs to ensure that information reaches people at risk from landslides and the local agencies that oversee land use and development.

“One thing that makes landslide hazards different from earthquakes or hurricanes or other types of natural hazards is that it tends to be dealt with at a local level,” Lyttle said. “There are lots of arguments in just about every community in the nation about whether to strictly zone or not.”

In some parts of the country, landslide-mapping programs have been discontinued because of the possible impact on property values, said Scott Burns, a landslide expert at Portland State University.

But plans are already in the works for a new landslide hazard map of Snohomish County, Lyttle said.

The question of a revitalized landslide program will also be on the agenda in June at the annual meeting of the American Association of State Geologists, Lyttle said.

USGS scientist Jonathan Godt met last week with staffers who work for Sen. Maria Cantwell and Rep. Suzan DelBene of Washington state, and Sen. Mark Udall of Colorado — which was hit by multiple landslides this past winter — to discuss possible ways to bolster landslide programs.

But money is tight, Lyttle said. “To carve out an increase for one program tends to mean that somebody has to find a place to cut.”

If nothing else, the Oso slide should spur mayors and other local elected officials to start asking questions about landslide safety, May said. “They should be talking about it and asking: ‘What are we doing? Should we be doing more?’ ”

Highland, of the National Landslide Information Center, is working on a pilot project to combine state landslide inventories as a small step toward a national inventory. But another project she planned to start this spring — to develop a new estimate of economic losses from landslides in Washington and Oregon — was canceled due to lack of funding.

Sandi Doughton: 206-464-2491 or sdoughton@seattletimes.com

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!

Four weeks for 99 cents of unlimited digital access to The Seattle Times. Try it now!