|

|

|||

|

|

Monday, November 13, 2000, 8:00 a.m. Pacific

New Money: Younger generation's expectations have become far greater than parents' By Chris Solomon

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Yet Kevin Finlay and Terri Miller talked through dinner and missed their movie.

Two years later they moved north. Kevin got a job on Boeing's B-2 bomber program. A few credits shy of an associate's degree, Terri worked a few jobs but mostly cared for their newborn son.

They now live with three children on a cul-de-sac in the Woodmont neighborhood of Des Moines. The Finlay house is a peach split-level with a broad view of the Olympics and of the bellies of incoming 757s that Kevin pieces together for $23 an hour at Boeing's Renton plant.

Kevin has worked at Boeing for the past decade, interrupted by a 2 1/2-year layoff. The household earned about $62,000 last year - counting dozens of weekends of Kevin working overtime, a Boeing bonus and Terri's part-time work during the holidays.

Since 1989, Kevin Finlay's hourly wage has virtually doubled - not bad for a guy who went to mechanics school instead of college.

Their income places the Finlays well above the middle of local households. The median household income for the Seattle area - the level at which half the households make more and half make less - exceeded $55,000 last year, according to Seattle Times estimates based on Census Bureau data.

Many families in the middle have fared well.

Puget Sound's median household income started the 1990s about $9,000 more than the national median; by 1998, the difference was about $16,000, according to The Times' estimates. That means the typical household here makes about 40 percent more than the rest of the country.

Still, it isn't surprising that families such as the Finlays can be disillusioned, according to Roberta Pauer, King County economist for the state Employment Security Department. After all, reminders of even greater prosperity are as close as the new sport-utility vehicle in the neighbor's garage, Pauer points out.

"In the old days, young couples weren't expected to have a home, much less have any money," she says.

"The same parameters of their life, the same things they have, if they were living in Des Moines, Iowa, they'd have a completely different perspective on how they're doing.

"There wouldn't be so much wealth above them."

Old cars, used toys

The television in the corner of the living room stands as tall as a man and is connected to a satellite dish that pulls in scores of stations.

The afternoon cartoons cast their blue glow across the toy monster trucks and building blocks of Shelby, 3, and 22-month-old Bryce. Around the corner in the kitchen, 10-year-old Tony often plays games on the computer that the couple bought with Kevin's bonus.

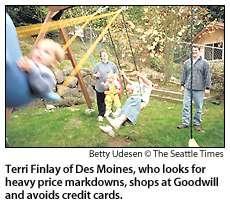

The back yard is a movable feast of Radio Flyer wagons, two swing sets, a hobbyhorse and a tricycle. The toy bin is so large that Bryce, the toddler, once fell in.

"The kids really don't want for much," says Terri, 32. She has a deep and frequent laugh that allows her to keep her sanity while keeping up with her children.

Caring parents, the Finlays keep a calendar filled weeks in advance with Cub Scout meetings and Tony's soccer games. An SUV and a minivan sit in the driveway of the home they bought two years ago for $153,000.

Despite their successes, Kevin and Terri agree it isn't how they pictured it.

"I'm 37," says Kevin, "and I thought things would go smoother."

'There's a certain image that you have: Get married, have a house, stay home with the kids and be able to afford that ... and you can't do that.' |

They live, they say, nearly paycheck to paycheck.

Middle-class families' discomfort is partly perception, but it's also reality, says Edward Wolff, a New York University economics professor who specializes in the economics of inequality.

While incomes of the middle class nationally have stayed steady, Wolff says their financial reserves have taken a tumble over the past two decades: "They don't have the savings for a rainy day to count on."

The Finlays are too happy and too busy to let their situation gnaw at them. But they are confused.

"There's a certain image that you have: Get married, have a house, stay home with the kids and be able to afford that . . . and you can't do that," says Terri.

Their frustration seems grounded in great part in a changing standard of what constitutes a middle-class life.

As cultural critic Barbara Ehrenreich has written, "In order to be middle class as our culture is coming to understand the term, one almost has to be rich."

By many people's standards today, the Finlays would not be considered frivolous. One of their chief indulgences last year was the more than $2,000 they spent on materials for the Cub Scouts.

Their cars are both more than a decade old. That big, $1,500 television was a steal at $800; the family watches it from a $15 sofa. The computer? Used. The toys? All bought at a discount or at Goodwill. They shun credit cards.

"We're being frugal to a certain point," Terri says. "We're trying to maintain a certain standard of living that we feel we're comfortable with."

That urge seems to be happening at the same time something else is shrinking: the amount of time people feel it should take to reach that dreamed-of lifestyle.

Different path for parents

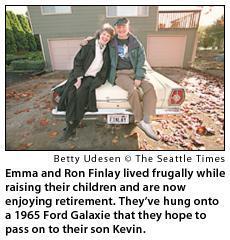

Across Des Moines, in a mint-green, 1960s-era home nearly surrounded by the homes of Boeing workers, the elder Finlays watch their son's situation with sympathy. But an unformed question seems close to their lips: When did having it all become a right of the young?

It was not that way when Ron and Em were a young couple in the early 1960s. The son of a well-heeled Boeing executive, Ron took a job at Boeing in 1960 as a cost estimator for new programs.

The adoption of their first son, Ron Jr., and the birth of Kevin in the early 1960s brought tight times. Wanting to live in the country, the couple bought a termite-ridden cabin on Beaver Lake outside Issaquah for $22,000 in 1962 and lived in it for a decade.

Ron Sr. worked - and worked. Weekends of overtime. Vacations spent training with the Army Reserve for extra cash to help the couple pay off another house in Eastgate.

Em did not work. "There was no question about me staying home with the kids," she recalls.

They did not dine out much. Cheap fun was dancing at the Officers' Club on Pier 91 or working with friends on charity guilds.

"We always had what we needed," Ron Sr. says.

Material success - that was for the future.

Then their goals shifted. By 1974 Ron Sr. had decided to become a preacher, and the family moved to rural Tennessee, where he attended a seminary. Preaching Sundays for $50 a sermon made the family have real purpose in each purchase, the couple say.

The time in the pulpit also taught the father something else. "When I became a preacher," he says, "I realized that people's expectations were their main source of problems."

He eventually was lured back to Boeing in 1986. He retired in May.

In the garage sits a newly leased 2000 Acura - the couple seem slightly embarrassed by its presence - their first new car in 33 years. After Em's recent heart attack, they splurged this fall on a two-week trip to Tahiti.

The younger generation seems to have little use for "delayed gratification" like this, Em says. These days, the first home the next generation buys "is exactly what you last lived in with your parents," she says. "And that's wrong."

"How necessary," she adds, "is it to have umpteen jillion toys for the kids?"

They are not harsh. Ron Sr. says he simply sees his son's family somewhat caught in "the groove everyone else is in."

Even the younger Finlays agree their expectations are not their parents'. "Instant gratification" and the desire to see their children well cared for play a big role. Complicating that, they say time and again, is the speed of life today.

"I think that's a lot of the reason we feel we have a hard time waiting for that purchase . . . we're real tuned in to that speed," Terri says. "You feel like if you wait for it, it will be gone."

It is perhaps understandable, then, why the Finlays do not feel they are jogging toward a distant goal, so much as sprinting on a treadmill.

"Quite a bit is eaten up, literally, by eating out because we're always on the run all the time," Kevin says.

That running has only gotten harder. In the past, Kevin worked hundreds of hours of overtime to pay the bills. Terri remained at home with the children - a decision made easier by the $1,200 monthly cost for child care for two kids.

But last year, when there threatened to be a lot of space beneath the Christmas tree, Terri started working part time at Toys R Us in Tukwila for $7.10 an hour.

Her paycheck is the family's spending money, she says. She recently worked a 23-hour shift to earn money for a craft show she wanted to visit.

"Sometimes you feel overextended - you're always running," she says, "but in the end we feel it's worth it."

Kevin is less sure.

In his father's day, a job at Boeing paid well and was fairly respected in the community. "To some extent there was some envy if you were at Boeing," Ron Sr. recalls. "They knew you were well taken care of."

The son sees that changing.

"Even when I was first hired here, everyone wanted to join Boeing and earn the big bucks," he says. Now, he says, guys on the shop floor are taking computer classes.

When he looks around King County, "It's not so much envy as, I have seen the fruits of other people's dreams," Kevin says. "We're not with the people who have taken advantage of all the economic gains."

The family's situation will only improve as the children grow and Terri finishes her associate's degree and gets a better job. Kevin and Terri know that.

And yet, at a time when dreams are coming true around them - that future seems harder to wait for than ever.

Chris Solomon's phone message number is 206-515-5646. His e-mail address is csolomon@seattletimes.com.

| Background, Related Info & Multimedia: |

|

| Then and now |

![]()

| [ seattletimes.com home ] [ Classified Ads | NWsource.com | Contact Us | Search Archive ] |

Each morning, Kevin Finlay heads to work at the world's largest airplane company. The company has also been the biggest producer of something else: Seattle's middle class.

Each morning, Kevin Finlay heads to work at the world's largest airplane company. The company has also been the biggest producer of something else: Seattle's middle class.