|

|

|||

|

|

Continued: One neighborhood and its identity crisis Background, Related Info & Multimedia: Differences just skin deep?

Berger, 73, has operated a barbershop out of his West of Market home for 16 years after losing his lease in downtown Kirkland. It is a throwback within a neighborhood struggling with the changes wealth has brought. Berger's house is simple, but the view from the barbershop window -- a skimmed Seattle skyline, the top of the Space Needle and Lake Washington -- is fancy. Farther up the hill on a corner lot, a fire pit rests beneath a tall flagpole in John Swan's front yard. Summer evenings, when the breeze blows toward the lake and away from his neighbors, he'll start a bonfire and roast wieners and marshmallows. "I sit on a lawn chair, enjoy an adult beverage and invite the neighbors to drop by," Swan says. The fire pit is encircled with concrete pavers that he bought for a nickel each at a scrap sale. Alongside his carport, red bricks from the old toll plaza of the Evergreen Point Floating Bridge are piled high. Swan recalls having to make numerous trips in his station wagon to haul them away. But he doesn't remember the project he planned to build with them. It's been so long. Julie Anne Chia, who lives in one of the big new West of Market homes, says she savors the down-home flavor of the neighborhood. She plans to take her infant son to Berger's barbershop when the time comes for his first haircut. "I think people might feel intimidated because the houses are big, but that doesn't mean the people who live there are intimidating," Chia says. "I wonder if the people who say they are intimidated are making an effort to meet the people inside the big houses." Loomis, the longtime resident with the historic home, has met few of her wealthy new neighbors. "Those of us who have been here for a long time and didn't pay a lot for our houses and didn't have a lot when we bought them, our lifestyles remain simple and non-ostentatious," she says. " They do different things than I do." Progress a relative term Eric Horvitz, a Microsoft Research group manager with a doctorate and medical degree from Stanford, does different things than Loomis -- and almost everyone else on the planet. The computer scientist's research focuses on "the use of Bayesian and decision-theoretic principles in the construction and operation of intelligent, flexible computer-based reasoning systems," his Web site says. He and his wife bought a house in 1994 on Waverly Way, a wide street tracing the shoreline. Horvitz worked with an architect to salvage the 1940s-era run-down house previously owned by a well-known downtown hardware store owner. But builders took one look at the plans and advised Horvitz he was better off starting from scratch. So Horvitz acquiesced to the bulldozer. He videotaped the inside and outside of the house for posterity and then memorialized the event as the rigs leveled the place in about an hour. A crowd gathered with him on Waverly to watch the Bryant house come down. "It had some history, but it also had become known around the neighborhood as 'the haunted house,' " Horvitz says. "It was unkempt and, at least in recent years, an eyesore." Not everyone was happy to see it go. As bulldozers flattened the past, an older man ambled past the crowd on Waverly. "He didn't really stop -- he just kept on walking," Horvitz recalls. "He made some sort of comment like, 'It's a shame. People have too much money these days.' My reaction was this was someone who feared change." When Horvitz studied the human mind at Stanford, he learned that change brings about thoughts of death and memories of loss. He figures the tearing down of the old Bryant house probably reminded the old man of his own mortality. The two-story house with a basement has four bedrooms, five full or partial baths and a mother-in-law apartment. "Our goal is for that house to be something people in the neighborhood are proud of," Horvitz says. He plans to have neighbors over for an open house once he is settled. Perhaps they'll chat about the speeders along Waverly. It's a problem that concerns Horvitz, as it has every West of Market neighbor since cars were invented. Changing of the guard The 32 homes that line Waverly Way are like courtside seats with unobstructed views of the lake. Great sightlines don't come cheap, and Waverly addresses lay claim to some of the highest residential land values in King County. A 12,000-square-foot lot at 422 Waverly is near perfection, with an angled slope that offers varying views, each stunning. A perfectly fine but far from perfect three-bedroom, 1,800-square-foot rambler built in 1952 sits atop the lot. The house boasts some bricks from the turn-of-the-century mansion that sat there before it. The mansion was built for Walter Winston Williams, who was secretary of the Moss Bay Steel Works in England and one of the players behind the 1888 incorporation of Kirkland Land and Improvement, which developed Kirkland and operated the old steel mill. Two city clerks also once lived in the old mansion, storing the city's financial records there before there was a City Hall. The lot is part of Kirkland's history. The rambler on the lot is soon to be history. It will be razed to make way for a mansion that likely will cost a few million dollars to build. The lot alone, with the doomed rambler atop it, sold for $1.5 million earlier in the summer. The seller was Rick Seim, a real-estate agent who bought the property in 1977 and leased the house the past six years. The house has picture windows, two fireplaces, a formal dining room and skylights. A sliding glass door leads to a brick patio where the view is Lake Washington, city skylines and the Olympic Mountains. When the house on this lot gets a second story -- and it will soon -- there also will be a view of Mount Rainier. The kitchen and bedrooms are small, however, and the bathroom has only a single-basin sink. "I had people come up to the house all the time, knock on the door and say, 'We'd like to build a house here that is appropriate for your lot,' which offended me when I lived here," says Seim, who has sold to someone who plans to build a house appropriate for the lot. Seim is apologetic and nostalgic over selling. His two boys grew up there. Seim maintained the yard for his tenants until last year and remains close with neighbors. "It's not just a financial decision, it's an emotional decision," Seim says. "Selling this home changes people's lives and lifestyles, and I'm sensitive to that." Views could be blocked, taxes could go up, and the character and culture of West of Market could change more than it has already. "We have sold it with the understanding that the home to be built will be tasteful and in character with the neighborhood," Seim says. "But once they buy, it's theirs, and really they can do what they want. We have lost our say in it." Space is tight in paradise Stephen Lutz, Ellen Lutz's husband, rides a tractor to mow the grass in what neighbors simply call "the lot" -- an 8,400-square-foot field adjacent to the Lutz home. For years, neighborhood pipsqueaks have played baseball on the lot after school. A gaggle of little girls, almost each one as blond as blond can be, borrow the lot as a practice field for their soccer team. The lot is one of the few developable open spaces left in West of Market. A neighbor recently filled in his back yard. Where there once was a tennis court, there now is a house with silver corrugated metal siding that was voted The Seattle Times/American Institute of Architects Home of the Year for 1999. "We love our new neighbors, but we also loved the tennis court and the airspace it gave us," says Stephen Lutz, a manager for a book wholesaler and Kirkland Kiwanis Club president. Already feeling squeezed, the couple have decided they will not piecemeal their own 29,000 square feet of land, which could accomodate three big houses. And the prefabricated house that Ellen Lutz's parents bought in 1946, including the covered outdoor patio her father built with tremendous pride, likely would be doomed. "I would hate to think of our beloved home as a knocker-downer," Ellen Lutz says. "But I'm sure the bulldozers would come." Stuart Eskenazi's phone message number is 206-464-2293. His e-mail address is seskenazi@seattletimes.com.

|

||||||||||||||||

| [ seattletimes.com home ] [ Classified Ads | NWsource.com | Contact Us | Search Archive ] |

Inside a garage converted into a barbershop, Ed Berger trims the ear hair of a customer as the Johnny Paycheck song "Take This Job and Shove It" flows from a tabletop transistor radio. The most Berger charges for a haircut is $9 for "long hair over ears," according to a plastic reader board on the wall.

Inside a garage converted into a barbershop, Ed Berger trims the ear hair of a customer as the Johnny Paycheck song "Take This Job and Shove It" flows from a tabletop transistor radio. The most Berger charges for a haircut is $9 for "long hair over ears," according to a plastic reader board on the wall.

Chia and her physician husband moved from California to Seattle two years ago. They hunted for a house in Medina, Hunts Point and other swanky Eastside neighborhoods before deciding on West of Market. The couple knocked down an old two-bedroom house and built a four-bedroom, 4,850-square-foot home with stained cedar siding.

Chia and her physician husband moved from California to Seattle two years ago. They hunted for a house in Medina, Hunts Point and other swanky Eastside neighborhoods before deciding on West of Market. The couple knocked down an old two-bedroom house and built a four-bedroom, 4,850-square-foot home with stained cedar siding.

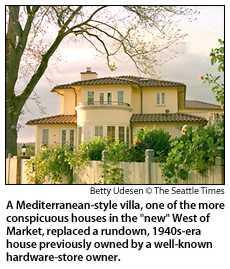

Where the Bryant house once stood, builders are putting the final touches on what may be the most conspicuous house in the neighborhood, a Mediterranean-style villa that Horvitz hopes to move into by the end of the year.

Where the Bryant house once stood, builders are putting the final touches on what may be the most conspicuous house in the neighborhood, a Mediterranean-style villa that Horvitz hopes to move into by the end of the year.