|

Monday, November 10, 2000, 8:00 a.m. Pacific

A grand indicator of wealth: demand for Steinway pianos

Background, Related Info & Multimedia:

By Stuart Eskenazi

Seattle Times staff reporter

A Steinway & Sons piano is the grandest in the grand-piano market. In the past few years, it also has become an instrument to measure Seattle-area wealth. A Steinway & Sons piano is the grandest in the grand-piano market. In the past few years, it also has become an instrument to measure Seattle-area wealth.

Annual sales of Steinway grand pianos in the Puget Sound area have more than doubled since 1994 and show no indication of slowing down, Steinway officials say. Buyers, some of them beginning piano players, are paying $70,000 to $90,000 to acquire a top-of-the-line Steinway -- an amount that would have bought a small house in South Seattle 10 years ago.

"A Steinway piano has the image of being the ultimate status symbol in your living room unless you have a Picasso or Rembrandt hanging on the wall," says Tim Miller, district manager for Sherman Clay, the area's exclusive Steinway dealer.

Manhattan-based Steinway handcrafts about 2,500 pianos for sale in the United States each year. About 150 of them will be sold this year in Sherman Clay's Seattle and Bellevue stores. The Seattle-Bellevue metropolitan area amounts to less than 1 percent of U.S. population but accounts for 6 percent of Steinway sales, making it one of the top markets.

The square footage of the Sherman Clay Bellevue store has tripled since 1995. Both the Bellevue and Seattle stores sell Steinways faster than the company can deliver them.

Andy Borowitz, an East Coast humorist whose book "The Trillionaire Next Door" lampoons the day-trader generation, is encouraged that the new rich are expanding their portfolios to include classical culture.

"Going from purchasing Humvees to purchasing Steinways is a vast improvement," Borowitz says. "My worry would be that they will find out that bossing around software engineers is much more fun than working your way through Chopin."

Jim Hebert, a market and economic researcher in Bellevue, says sales of all kinds of luxury items have soared.

And other music stores report that their sales of competing brands of high-end pianos are also increasing.

Auto sales in the region have increased 22 percent over the past year with much of the growth in the high-end vehicle market. Yacht sales are so brisk that dealer inventories are on back order.

The area is suffering a shortage of stable space for horses because so many people are becoming involved in equine sports once dominated by people with the titles of prince or dame.

And sales of second homes are off the charts, Hebert says. He points to a hideaway community in Cle Elum featuring golf and equestrian courses. Buyers snatched up 301 lots in seven days.

When it comes to buying Steinways, high-tech millionaires only have to follow the lead of the master. Bill Gates owns a 7-foot Steinway, Miller says.

Hundreds of the world's finest pianists also play a Steinway or they play nothing at all. Classical artists Van Cliburn and Evgeny Kissin, pop artists Billy Joel and Randy Newman and jazz artists Herbie Hancock and Ramsey Lewis all swear by them.

Steinway de rigueur is trickling down.

"A Steinway sends the signal that even if you don't know what you are supposed to do with all of this money you've got, you can be assured that you didn't do something stupid with it," Miller says.

The signal is hard to ignore since a grand piano fills much of a room.

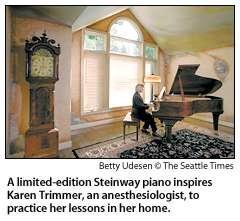

Karen Trimmer, an anesthesiologist starting her fourth year of piano lessons, is redoing the living room of her Woodinville home. Her interior decorator remarked that Trimmer's black baby-grand piano clashed with the earth tones that saturate the southwestern motif she is trying to create. That gave Trimmer an excuse to upgrade.

In February 1999, Trimmer's husband came down with pneumonia and the couple canceled their annual winter cruise. During that time, she attended a Sherman Clay special sales event at the Columbia Winery in Woodinville. Her eyes locked on to a Steinway there.

For about $70,000, Trimmer took home her object of desire: a limited-edition 5-foot, 10.-inch Steinway grand piano. Only 200 were made to commemorate the 200th birthday of the company's founder, Henry E. Steinway.

The piano tracks a 1902 design of Joseph Burr Tiffany, of Tiffany & Co. fame, who worked on Steinway's first commemorative piano, presented to President Theodore Roosevelt in 1903.

Trimmer loved the piano's East Indian Rosewood finish, a reddish-brown hue that agrees with the brown leather sofas, orangey terra cotta walls, pale brown hardwood floors, antique grandfather clock and subdued Tiffany floor lamp that grace her living room. She also loved the detail of carved moldings that run the length of the instrument.

Her husband, an oral surgeon, doesn't play but enjoys photographing the piano and hearing his wife play.

Trimmer says her purchase of the Steinway had nothing to do with status.

"I wanted this piano for the sound more than anything," says Trimmer, who grew up in Virginia and moved to the Seattle area in 1992.

"It was expensive, but not that expensive compared to some of the other purchases we've made."

A larger model of the 200th anniversary limited-editions was purchased in February 1999 by a high-tech professional from the Eastside in his mid-30s only two months after he started piano lessons. He changed his mind about renting a piano for $30 a month and instead bought the Steinway, outfitted in a rare wood finish, for about $90,000.

"I didn't buy it to make anybody other than myself happy," says the man, who did not want his name published for security reasons. "It was a really selfish purchase. Initially, I wasn't sure how much money to drop on this because I was just starting out. I mean, what if it turned out that I wasn't interested in pursuing it?"

A 28-year-old Microsoft employee from North Bend who has played piano since he was a kid upgraded in February from an electronic keyboard to an $80,000 nine-foot Steinway concert grand with a black satin finish.

"It was all about the recognition of quality," says the man, who also did not want his name published. "I suppose, though, it is kind of like owning a Ferrari, which I don't, by the way. People say 'Ooh!' But I don't go around telling everyone I bought a piano. It's not a good pick-up line in a bar."

Microsoft program manager Sue Bohn, who grew up on a farm in North Dakota, parlayed her company stock options into a $71,000 full-size Steinway concert grand in February 1998. The 9-footers aren't usually bought for a house, but Bohn says her Redmond home has cathedral ceilings and a large living room.

"It's not excess," says Bohn, 41. "It's quality. It's an investment. I can sell it someday for more than I paid for it. I can pass it down through my family one day or donate it to a church or a concert hall or a university."

Bohn's mother started teaching her to play piano when she was 5, and she minored in music in college. She played keyboard for a rock musical production on the Eastside.

She always knew she wanted to buy a full-size grand piano with her Microsoft money but never entertained the thought of a Steinway until she happened upon a Sherman Clay booth at a Bellevue home show. For kicks, she agreed to attend an appointment-only private showing of Steinways at the winery hosted by Sherman Clay. The 9-foot, black satin concert grand was lonely in a corner. It was love at first sit.

"I started playing it, and my husband knew at that point I was going to buy the piano," she says. "He saw the look on my face and said, 'Oh, oh!' "

But Bohn is a deliberate consumer. She needed a night to sleep on it. Instead of snoozing, she obsessed.

Was she conflicting over her conservative, Midwestern values? No. She knew the piano was going to be offered for sale to the public the next day, and she worried some Microsoftie with more stock options than her was going to get to it first.

"The emotion that was strongest that night was that someone else was going to get this gem, and I deserved it," Bohn says. "All I could think of was that it should be mine."

Stuart Eskenazi's phone message number is 206-464-2293. His e-mail address is seskenazi@seattletimes.com.

|

![]()

A Steinway & Sons piano is the grandest in the grand-piano market. In the past few years, it also has become an instrument to measure Seattle-area wealth.

A Steinway & Sons piano is the grandest in the grand-piano market. In the past few years, it also has become an instrument to measure Seattle-area wealth.