GOLDBOTTOM, Yukon Territory - If there is gold in them there hills, then the hills will have to go.

"Gold mining is about moving ground," explains Deborah Millar, a second-generation miner on this historic creek near Dawson City. "And we have a lot of ground to move."

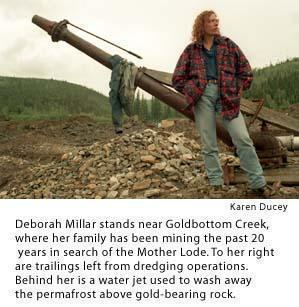

Millar stands on a crude road cut into a hillside overlooking Goldbottom Creek - or, at least, what used to be Goldbottom Creek.

Today the creek is a muddy lake, dammed somewhere above us so the Millar family can scour its valley in search of golden flakes and pebbles.

"We keep moving the creek bed," Millar says. "You can't mine in water, so we move it to this side so we can work that side, and then back again to work this side."

The result is not a pretty sight. The valley is a confused mass of dirt and gravel piles, with muddy trickles flowing between them.

But gold mining isn't about aesthetics. To reach the Millar family operation, we drive up the Klondike River Valley through a macabre moonscape of massive gravel tailings left by a half-century of industrial gold-dredging.

We stop and explore an abandoned dredge, five stories tall and 200 feet long. This gargantuan machine spent decades grinding through the creek bed, floating on a mobile pond of its own making, inching forward as it scooped up tons of river rock, spun and shook and sifted it, separated the potential paydirt, then dumped the tailings behind it.

In the 1950s and '60s, the corporate miners gave up and went home, leaving their mess for Mother Nature to deal with.

Now the miners are back - not the Wall Street behemoths, but 150 or more small, mom-'n-pop operations like the Millars'.

"We've been working this creek for 20 years," says Deborah. "It's what we do."

Deborah Millar is schooled in computers, but comes honestly by her Klondike fever.

Len and Rona Millar, her parents, came north on their honeymoon in 1957 and stayed. Len worked as an administrator for the mining company, Rona as a nurse. They raised four kids in Dawson, dabbling on summer weekends in recreational gold panning.

Twenty years ago, after the industrial miners moved out, the Millars stepped into the vacuum, eventually accumulating 70 claims along four-plus miles of this valley.

It's a historic site. In 1896, the valley was being worked by Robert Henderson, the pioneer prospector who steered others toward the nearby creek and made them wealthy men. Goldbottom itself became a town of 3,000 people, a base for the prospectors who mined the valley.

Goldbottom seemed to hold great promise. It flows at the foot of King Solomon's Dome, the weathered peak that some locals still believe conceals the legendary mother lode.

Len Millar died several years ago, but Rona and her grown children continue his work, spending their summers in an 80-year-old roadhouse, methodically sifting through a river valley that has been worked for a century.

"These days, most people are mining the tailings," Deborah explains. "What's left is mostly the fine stuff that got through the dredges."

The Klondike placer is composed of flakes and tiny pebbles broken down by millions of years of weathering, deposited in streams and working their way down to bedrock.

"The paydirt is in that band five or six feet above bedrock," Deborah says, pointing to a 40-foot-high earthen wall bulldozed out of the hillside. "It's about 40 feet beneath the permafrost."

A million or so years ago, this was the creek bed, and now it contains bits of placer gold.

To reach it, the Millars use high-pressure hoses to wash away the surface permafrost, then bulldoze the middle layers aside. Then they use a front-end loader to scoop up the gravelly paydirt and dump it into a mechanical sluicebox.

The sluicebox is a scaled-down version of that huge dredge down the road. It spins and sifts the rock, dumps the large stones and sluices the paydirt down a spillway carpeted with Astroturf. The gold is supposed to sink into the Astroturf.

The Millars collect the gold, melt it into bars and deliver it to an agent. The agent assays it and writes a check for its value - "minus assay charges, refining charges, freight charges, bank charges, royalty charges . . ."

There have been good years. But this one has been rough. Too much muck, higher costs to meet new environmental rules, lower gold prices. And the ground they're working has not been producing.

To make ends meet, Deborah's sister-in-law works in Dawson, and the family now runs tours for outsiders who want to see a working gold mine. Deborah is an excellent tour guide.

"This is actually virgin ground. It's unlikely the early prospectors worked it," Deborah says. "We figure we need to get 3 ounces per hour just to meet expenses, and we're not getting it . . .

"So we're going to move further into the hillside."

I cringe a little. It seems like an awful lot of destruction to extract a few ounces of glitter to be melted down and stored in some government vault.

But it's difficult to see this family as pillagers of the very environment they choose to live in.

"This is bare-bones mining," Deborah says. "No mercury, no cyanide, no chemicals. Just lots of water and bulldozers. We turn the ground upside down, take out the gold we can, and then we put it back."

"I went Outside for several years, became a computer geek," Deborah says, gazing up from the tailings to forested slopes of Solomon's Dome. "But now I've come back to stay, and I can't remember why I wanted to leave."

Even after 40 years, her mom feels the same way.

"It's a way of life up here," says Rona. "It's what we do. You're your own boss. For five months, we work long, hard days, and then we talk about it the rest of the time. Gold allows us to do that."

She follows Deborah's gaze up the slopes of Solomon's Dome.

"And besides," she adds, "there's a mother lode up there. And we haven't found it yet."