SHEEP CAMP, ON THE CHILKOOT TRAIL - One destination. Two routes.

A century ago, Mont Hawthorne stood on the docks of Skagway, weighing his options for getting to the Klondike gold fields:

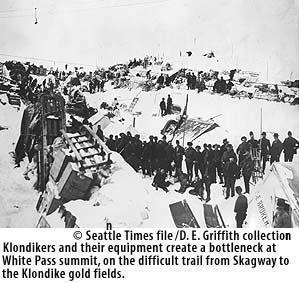

-- One option was White Pass, which begins at Skagway. It's lower at 2,900 feet, but also longer by some eight miles. In the beginning, it was suitable for pack animals. But the narrow trail was carved into a mountainside, a death trap that eventually claimed thousands of horses.

If you waited too long and the snow began to thaw, it turned to mush, then to mosquito bogs on the Canadian side. And whatever the temperature, you had to deal with Soapy Smith's gang of thieves and con men.

-- The other option was Chilkoot Pass, which begins at Dyea, five miles up Lynn Canal. At 3,500 feet, it's higher, steeper and shorter. All of which made it the route of choice for most Klondike stampeders.

Mont, however, opted for White Pass. He bought a pony to pull his sled and started out, taking advantage of the cold weather and hard-packed snow to move his 2,600 pounds of gear.

"I planned on making two trips a day," Mont recalls. "I'd take my stuff ahead for about six miles, then I'd unload it where I aimed to make my next camp, then go back for another load. . . .

"It took at least eight trips to move my whole outfit. At the end of four days, making two trips a day, I'd have moved ahead. . . . Then I'd go up where the cache was, pitch my tent over my outfit, make my camp, and the next day take the first load again.

"That meant, countin' the back trips, I made eight round trips of 12 miles every time I moved my outfit. I walked 96 miles for every six miles I gained on that blamed trail. And that was just the best I could do."

Mont's best was far better than most.

While others lingered in Skagway and succumbed to meningitis, dysentery or sheer exhaustion, or were victimized by Smith's gang, Mont went to work.

It took two weeks to move his outfit across the pass.

Mont held off two trailside thugs with his .44 revolver. He nearly collapsed of exhaustion, but nursed himself back to health. Despite all that, he still was one of the early arrivals at Lake Bennett, headwaters of the Yukon.

In the summer of 1997, I stand at much the same spot in Skagway and weigh my options.

Today, you can step aboard the White Pass and Yukon Railway and be over the summit within an hour. Hundreds of cruise-ship passengers do it every day. You can rent a car and be in Whitehorse or Dawson by sundown.

But I opt for the Chilkoot Pass, which is largely unchanged from a century ago. Mont seems to approve.

I hoist my 50-pound-plus pack and groan. It's the first time in some 20 years I've carried one of these things - except for a few warm-up trips through the neighborhood park.

Dyea, once a rowdy trailhead city with hotels and saloons and barber shops, has long since been reclaimed by the coastal rain forest. All that's left are the rotted stumps of what was once a milelong wharf over the long tideflats, and a tiny cemetery with the graves of those who died in the tragic snow slide of 1898.

We begin our trek, up and over a rocky hill, then back to a muddy trail through cottonwood trees alongside the roaring Taiya River.

The Chilkoot runs almost due north, up a splendid river valley carpeted with bracken ferns, berry brambles, devil's club and blooming dogwood.

The trail isn't easy - especially for a 49-year-old, overfed, ink-stained wretch such as myself. There are jagged rocks and bug-infested bogs to negotiate.

Yet, each turn in the trail offers a reward - a 100-foot waterfall on the steep slopes, a mossy grotto beneath its conifer canopy, a glimpse of an ice-blue glacier that is part of the vast ice fields clinging to the tops of the mountains above us.

And there is the company. Alaskans, Canadians, Germans and Czechs, 10-year-olds and 60-year-olds, all undertaking the same journey into the wilderness, into history and into their imagination.

Two days and 12 miles of trekking bring us to Sheep Camp, a favorite stopover, where I drop my pack, collapse against a log and find myself sitting once more with my historical friend.

It was just like Mont to come back over the Chilkoot. His outfit was safely cached at Lake Bennett. He wanted to get back to the coast to see his old family friend, Stanley Grimes, who'd come north on a later boat and promised to bring mail. Besides, Mont had not seen the now-famous Chilkoot Trail.

Here at Sheep Camp, yet another tent city in the midst of a wintry wilderness, he asked around until he found Grimes.

"Sure enough, Stanley had brought some letters from my folks. Mostly it was Mama telling me to take care of myself and not catch cold. I'd caught one by then anyhow."

Grimes had lumber and a cookstove hauled up from Dyea and was running a restaurant at Sheep Camp.

Grimes was a classic case of a Klondiker who never intended to reach the Klondike. The stampede was good business.

"Grimes told me to watch out for snowslides on ahead," Mont recalls. "That whole country is full of glaciers and snowbanks that pile up on ledges. Then the wind starts thawing them in underneath, and pretty soon they go crashing down."

Mont bade farewell to his old friend and climbed back over the summit to start building his boat for the trip down the Yukon River.

A week later, the grim news made its way over the human telegraph to Lake Bennett.

There'd been a terrible slide on Chilkoot. None of the Indians wanted to go up the pass that day. One of them told Grimes to get off the pass because the snow was thawing and a slide was coming.

Grimes packed a few things, secured his tent and headed down the trail toward Dyea.

"Just then, the slide come and it got him. It was one of them freak things. That slide never touched his tent; if he'd stayed there, he could've gone on living," said Mont.

"But instead, he was dead, buried right there under the snow at the foot of the Chilkoot Pass along with the others."

As many as 70 people died in that slide, April 3, 1898. Most of them are buried in Dyea.

Legs still aching from my two-day trek, I stroll through the rustic, overgrown camp. In the mist of a bramble, I can see rusted pieces of an ornate cast-iron stove.

I wish I could stop at the Grimes place, nurse a 25-cent cup of coffee and listen to Mont and Stanley trade stories.

And I wish I'd stopped - just me and Mont - at that little cemetery in Dyea to pay our respects to a fellow traveler.