MARSH LAKE, Yukon Territory - With a warm northern sun and a fresh breeze at our backs, we are well under way on the final leg of our journey to the goldfields.

Life is good, and so are our prospects. We paddle downwind along a wilderness - passing not so much as a tent or a cabin on 20 miles of lakeshore.

Never mind the dark clouds and steeply slanted gray bands forming on the broad horizon. They must be 30 or 40 miles off. Not our problem.

I quit paddling for a few minutes, drifting on that tail wind and pull my tattered copy of Mont Hawthorne out of his waterproof bag. One hundred years ago, he felt the same way.

"We could look up at the sun shining on the snow-covered mountains and knowed we didn't have to

climb no more of them. We was just as excited and just as hopeful as when we started from home."

But he added, rather ominously, "In the Yukon country, when the weather changes, she changes fast."

At the north end of the lake, we begin to feel the tug of the river - not a real current but a gentle gravitational pull. We round a bend and know we are finally on the fabled Yukon River.

It's 30 miles downriver to Miles Canyon and Whitehorse. We hope to ride the river current, portage around the dam at Whitehorse and continue on to Lake Laberge.

Five miles downstream, we encounter a low dam, beach our boats and examine the aging, self-service lock at one end. Our choices are to carry our boats around, or operate that lock.

"Or, then again . . ." offers Glen Sims, my fellow kayaker.

He is studying that dam and its one-foot-high spillway. He has a mischievous gleam in his eye.

No way, I say.

"Piece of cake," he says.

So we climb back into our boats and shoot the spillway. No problem.

That's what Mont would have done.

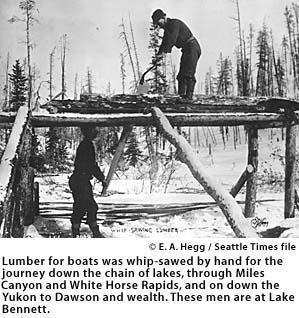

A century ago, this stretch of river was a tad too downhill for many of the Klondike stampeders. Miles Canyon and Whitehorse Rapids, whose froth reminded pioneers of the wind-whipped mane of a white horse, claimed dozens of boats, tons of gear - and some lives.

Mont and and his faithful dog, Pedro, walked the edge of the canyon, studying the river. "Them rapids was the prettiest sight I ever seen," he said. "But there wasn't no stopping from the head of Miles Canyon to the place below Whitehorse Rapids where the cemetery was filling up with the boys who hadn't made it."

Mont calculated his course and shot the white water with no problem. Then he stopped to steer some fellow stampeders through the course.

Today, the rapids have been transformed into a docile lake, backed up by a dam that feeds hydropower to 24,000 people in Whitehorse. All that's left of the notorious white water is a few hundred yards of foam and spray beneath the dam.

But the engineers have yet to tame the Yukon weather. As we paddle northward through the snake-like bends of the upper river, those brooding storm clouds have moved closer. Now they're firing bolts of lightning and rolling thunder first from the west, then the east, and from dead ahead.

Brief northern squall, we figure. Paddle on. Klondike ho.

Ten miles above Whitehorse, it hits us - first a drizzle, then a downpour, then a cloudburst with lightning and thunder and dime-sized drops that sting. It's as if Mother Nature had scooped up part of Marsh Lake and dumped it on us - a stern reminder that the North is not to be taken lightly.

Already drenched, we slide into our rain gear and paddle on.

The torrent takes on a beauty of its own. Each droplet triggers an explosion on the water surface; millions of mini-splashes create a foot-deep mist across the river's surface.

Occasionally, we seem to paddle out of the worst of it, only to ride the current around a sweeping bend and back into the downpour.

My rain gear immediately becomes drenched, and I resolve to have a chat with the salesman who insisted it was waterproof. He could have sold it as a sponge. I quit paddling every minute or so to drain the water from my sleeves.

We press on through Miles Canyon, whose frothy, 4-foot crest struck terror into the hearts of the Klondikers. Today it's a nice ride, if it isn't raining.

The river takes us into disappointingly docile Lake Schwatka, where we hug the shoreline to avoid being easy targets for lightning bolts. It is still raining when we beach our boats next to the Whitehorse Dam and examine our options.

The biggest problem is yet to come. The combination of spring runoff and the cloudburst has turned the spillway into a torrent. To relaunch our boats, we have to carry them a half mile down a service road, then a narrow trail to a rocky ledge - all in a persistent rain.

We go to work, moving the heaviest gear by hand, then the boats. Weary and soaked to the skin, with 100 pounds of boat on my shoulder, I find myself wondering if I wouldn't have preferred the white water.

Mont did. "Lots of men like to gamble with cards," he observed. "I like to run white water. Shooting down them five miles kept a man on his toes. . . . Just about the time a fellow would figger he was safe and could take it easy and look around a little, there was another blind channel."

Finally, the rain lets up and a patch of sun peeks through the back edge of the storm. With our outfits moved to that rocky ledge downstream, we contemplate the 100 yards of rapids below us and decide to save it for another day.

We set up camp beneath power lines and a few feet from a substation - hardly a wilderness experience. We hang our wet gear on tree limbs and crawl into our sleeping bags.

My mind journeys on, riding a stiff current and a fresh breeze downstream to the Klondike country.