HOMEWARD BOUND - The plane lifts off Dawson's gravel runway, gains some altitude, then banks southward over the Klondike goldfields.

Mont Hawthorne, my historical companion and guide, presses his handlebar moustache to the glass for one last glimpse of the Klondike River and Bonanza Creek below. Even from the air, those valleys appear deeply scarred by a century of relentless digging - by pickax and shovel, bulldozer and industrial dredge.

Mont is absorbed in memories of his last departure in 1899, second thoughts, perhaps, about his two-year adventure, about what he accomplished here and why.

"Us prospectors hadn't done much after all by spending our time digging those blamed holes and burrowing through those tunnels," he observes wistfully.

"And I sure didn't know then that the government was going to take that gold and bury it all over again at Fort Knox."

Beneath all the romance of the Klondike, beyond the dramatic photographs by Hegg and Kinsey, there is something fundamentally preposterous and tragic about the human stampede launched in Seattle 100 years ago this week.

From the outset, it was a bizarre exercise in futility. By the time the steamship Portland pulled into Seattle with its much-ballyhooed "Ton of Gold," most of the Klondike gold fortunes had already been staked. From a practical standpoint, the gold rush was over before it began.

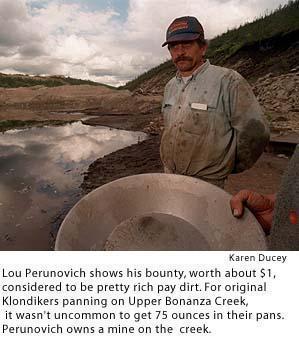

Yet, thousands of people - from streetcar conductors to governors - flocked northward like so many sheep, each determined to find his fortune in the chilled waters of Bonanza Creek.

Unlike most of the stampeders, Mont Hawthorne knew what he was doing. He was an experienced outdoorsman who crossed the plains in a covered wagon and sailed up the Inside Passage. He set out well-equipped.

Still, it took him six months to reach the goldfields and a winter of backbreaking work in sub-zero temperatures to barely recoup what it cost him to get there.

For others, it was worse. They set out ill-informed and ill-equipped and paid dearly for their errors. Of the roughly 100,000 who tried to reach Dawson, about 60,000 never made it. Hundreds died en route, or fell to typhoid or scurvy in the goldfields.

Still, for Mont and thousands more, there were few regrets. The pay dirt was measured in terms of memories, a grand, shared adventure that has long since become woven into the fabric of Pacific Northwest life and culture.

Commercially, Seattle mined the Klondike for 10 times its value in gold. In the first six months alone, local merchants sold $25 million worth of food and gear. The value of the gold taken from the Klondike during the same period was about $2.5 million.

Those profits, however, came at the expense not only of the stampeders, but of the Yukon natives, for whom the gold rush was an enormous tragedy. Entire tribes and villages were decimated by diseases to which they had no immunity. The invaders were oblivious to native rights to land that had been theirs for thousands of years.

Fortune and famine, adventure and tragedy. Even a century later, none of it makes much sense.

Gold fever

Gold does that. For at least 5,000 years, the yellow metal has driven human beings to insane, inhumane and frequently self-destructive behavior.

From the Sumerians and Egyptians to the Aztecs and Incas, gold has driven people crazy. The Egyptians enslaved whole populations to mine gold to decorate the Pharaohs' tombs. Gold drove the politics of the Roman Empire; the man with the gold controlled the army and therefore the empire.

This for a scarce element, most of which remains entombed deep in the earth - a glittery metal with many unique qualities but few practical uses.

Gold is extremely dense, heavier than granite and 19 times heavier than water, which explains why it is found in creek bottoms. A ton of pure gold, worth more than $10 million at today's price, would melt down to a cube not much greater in size than a cubic foot.

Yet, it is also extremely malleable, easy to craft into rings and goblets and crowns.

When found, it is in relatively pure form, requiring little or no processing. It is virtually indestructible, so people are constantly melting it down and reworking it into something else. Today's shiny, new wedding ring could contain gold from a long-lost crown of Cleopatra or a Spanish treasure chest.

Gold has been treasured primarily for its appearance, which it owes largely to its unique color and the fact it does not oxidize. To the ancients, the yellow glitter conjured up images of the sun and of immortality, thereby lending it religious significance.

For these reasons and more, gold became the unit of exchange from ancient Babylon to modern-day Dawson City. It was easily turned into coins, and later to paper certificates backed by gold deposits.

Today, more than 90 percent of the world's gold lies in government vaults, theoretically backing up money systems, lending stability to national economies.

But that began to change a century ago, and is still changing. Today, gold has been largely replaced by the U.S. dollar, judged to be more stable and far less scarce. And these days, kings and nations are far more likely to go to war over oil.

That fundamental change had begun to take place even as Mont Hawthorne and the others stampeded north, lending yet another element of futility to their obsession.

So why go North?

But if Mont and friends set out on a preposterous and futile mission 100 years ago, then what about our return?

Over the past month, we have steamed together up the Inside Passage to Skagway, there to fend with hordes of tourists unleashed by the cruise ships. We have hauled 60-pound packs 35 miles up the Chilkoot Trail and down the other side of the pass. We have paddled kayaks through a stormy Upper Yukon, portaged the Whitehorse Dam in a driving rain, and paddled the river 500 miles through the sub-arctic Yukon wilderness.

There are far easier, faster ways to reach the Klondike. Our flight home will cover that monthlong journey in about four hours. But that would have missed the point.

If this was yet another journey of futility, then we had plenty of company. Along the way, we encountered scores of sensible people undertaking similar journeys. I think of Chris Syrjala, the Seattle mom camped with her four kids on the stern of the Alaska ferry, all off on a thoroughly impulsive jaunt to the North country.

I think of Matt and Travis, 20-somethings who met on the bus to Whitehorse, rented a canoe they did not know how to paddle, and launched themselves on a 450-mile expedition down the Yukon. Along the way, they saved a man's life - and lived an experience neither will ever forget.

I think of Lou Johnson of Fort Selkirk and the Millar family of Goldbottom, hard-working and intelligent people who have escaped The Outside and made new lives in the supposedly inhospitable Yukon wilderness.

The impulse that triggered the stampede of 1897-98 lives on a century later in these Northern woods.

Sure, we have our Microsoft and Boeing, Starbucks and Nordstrom, big-league baseball and first-quality theater. But those institutions lure people here with ease because of the promise of something else.

People who migrate here still come in large part for those things that cannot be found or experienced in Des Moines or Dallas or Burbank. They are lured to the Northwest by a sense of adventure, by proximity to nature - be it Puget Sound, the North Cascades, the Inside Passage or the Yukon River.

Most will never paddle down that wild river, but it is important to know they could if they decided to.

The North will always beckon

For the past month, Mont and I have journeyed northward to that drum, to the quiet rhythm of Mother Nature, where we arrived as strangers and parted as friends reacquainted.

Maybe we needed to simplify our lives, to briefly escape the fluorescent lights, traffic jams and elevator music back home. Maybe a month in the North gave us the chance to take a fresh look at how we live our lives, how we relate to the world around us, and to assess what we might want to do differently.

After his return to Oregon in late 1899, Mont Hawthorne never went prospecting again. He bought a small farm next to his brother's in the Hood River Valley and raised nursery stock and apples.

"I'm keeping my pack straps handy," he told his mother. "If I ever get the gold fever again and try to head off for the ends of the Earth, you just tell me to strap 150 pounds on my back and walk up around Smith's Point until I get it out of my system."

But rest assured that Mont never quit looking North. He made several trips to Southeast Alaska, helping to build and operate salmon canneries. He hiked old Indian trails up and down the Washington coast, scouting for cannery sites.

His niece, Martha McKeown, grew up listening to Mont in the evenings, sitting in his favorite chair, retelling his stories about the Chilkoot Pass, Whitehorse Rapids, Soapy Smith and Bonanza Creek. Eventually, she wrote them down and published them, providing me with my Klondike companion.

Those stories are the real Klondike gold.