|

|

| STEPHANIE SINCLAIR / CHICAGO TRIBUNE |

| Iraqi children wear T-shirts supporting Saddam. The mortality rate for infants and children under 5 skyrocketed after the Gulf War and imposition of sanctions. |

|

HARD SANCTIONS

Iraqis suffer under U.N. restrictions as their effectiveness and morality are debated.

U.S. foreign policy after Sept. 11, 2001 was clear-cut for awhile.

Perhaps the most inflammatory issue on Iraq has been the economic sanctions that the United Nations Security Council unanimously imposed in 1990 after Iraq invaded Kuwait.

The U.N. says it will enforce those sanctions until Iraq is no longer pursuing weapons of mass destruction and has destroyed stockpiles of such weapons and long-range missiles.

Foes of the sanctions contend they target civilians, not the government, and have caused undue hardship on Iraqis, including hundreds of thousands of children's deaths.

They say that because of sanctions, Iraqis have lacked food and medicine and have been unable to repair water and sewer systems and power grids destroyed by U.S. bombing during the Gulf War.

Supporters of sanctions argue that sanctions are needed to keep Saddam in check.

As Peter Hain, a minister in the British Foreign Office, said:

"There's $24 billion of oil wealth under the control of the United Nations that he'd like to get his hands on, to re-arm himself to inflict tyranny in the region and on his own people again, which he has not been able to do under the sanctions regime."

'A HARD CHOICE'

Still, the humanitarian suffering linked to the sanctions has vexed the West. Then-chief U.S. delegate to the United Nations Madeleine Albright was asked by Leslie Stahl in a "60 Minutes" interview in 1996 about reports that half a million children had died and whether the price was worth the benefits of sanctions.

Said Albright: "I think this is a very hard choice, but the price — we think the price is worth it."

It is a statement that foes of sanctions repeat angrily and regularly.

Foes of sanctions oft point to two U.N. reports issued in 1999.

A Security Council's special panel to report the effects of sanctions, released in March 1999, said:

"In marked contrast to the prevailing situation prior to the events of 1990-91, the infant-mortality rates in Iraq today are among the highest in the world, low infant birth weight affects at least 23 percent of all births, chronic malnutrition affects every fourth child under 5 years of age, only 41 percent of the population have regular access to clean water."

A UNICEF report of August 1999 said children younger than 5 were dying at more than twice the rate of 10 years ago.

Sanction backers argue that Saddam could easily end sanctions by fully cooperating with the U.N.

And they argue that Saddam is not directing the resources he has, legal oil sales and black-market sales, to the Iraqis, but is squandering them on palaces, other luxuries and weapons.

Foes of sanctions argue Saddam's resources — legal and illegal — are not enough to rebuild the country's shattered infrastructure, nor to feed the people and supply the hospitals.

Furthermore, they say, sanctions have prevented the importation of many vital items, such as chlorine and pumps, that would be used in water systems, because they also can be used in weapons production.

OIL FOR FOOD

Since 1996, Iraq has been allowed to sell oil to raise money for humanitarian relief. Sanctions foes say the program has been too little too late.

Originally, Iraq was allowed to sell up to $2 billion of oil every six months. That amount has expanded through the years to where it is now open-ended. About a quarter of the money goes to Kuwait as war reparations, and about 3 percent goes to the U.N. for administration of the program.

Profile: Saddam Hussein

A skilled practitioner of treachery manipulates his way to power.

|

|

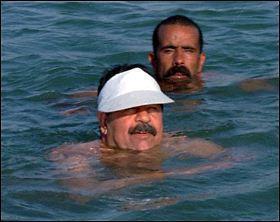

| IRAQI NEWS AGENCY / THE ASSOCIATED PRESS, 1997 |

| Saddam Hussein, foreground, swims in the Tigris River to open a competition held to mark his 1959 crossing after a failed assassination attempt on a prime minister. |

|

Saddam Hussein was born in 1937, in a village near Tikrit, a poor descendent of Arab tribesmen. His father either died or disappeared before he was born, and at age 10 he was sent to Baghdad to live with an uncle.

At 19, he joined the Baath (renaissance) party, which preached Arab nationalism, unity, secularism and socialism.

According to his official biography, Saddam was injured in the assassination attempt in 1959 against Iraqi Prime Minister Abdel Karim Qasim. Legend has it that he escaped Baghdad by swimming the Tigris, used a knife to dig a bullet out of his leg and walked to Damascus. He eventually moved to Egypt.

He later returned to Baghdad and reportedly helped organize the militia that helped the Baathists' successful 1963 coup.

Ahmed al-Bakr, Saddam's cousin and longtime Baathist leader, became president after the coup, and Saddam was head of the secret police.

In 1979, Saddam forced Bakr into a resignation and became president.

There is a chilling story that shows how Saddam would retain power. Upon deposing his cousin, Saddam called a meeting of hundreds of Baath party leaders where he accused some 60 men of treachery, removed them from the crowd and had them executed. He then distributed video of the meeting around the country. More executions quickly followed, perhaps in the hundreds, before the party's purge was complete.