|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

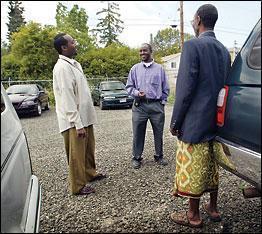

STEVE RINGMAN / THE SEATTLE TIMES

Fledgling auto dealer Abdisalam Yusuf, center, talks cars with Olad Omar, left, and Haji Mohamed Abdi. After Sept. 11, government investigations in their Seattle neighborhood added to the worries American Muslims faced from scattered threats and incidents of violence around the country.

|

MUSLIMS IN AMERICA faced unprecedented scrutiny — from the U.S. government and the public — as well as hostility and violence after Sept. 11. For Seattle-area Somalis, their Muslim religion as well as their culture were factors in an unusual pair of government investigations. One year later, the community cautiously moves forth.

MUSLIMS IN AMERICA faced unprecedented scrutiny — from the U.S. government and the public — as well as hostility and violence after Sept. 11. For Seattle-area Somalis, their Muslim religion as well as their culture were factors in an unusual pair of government investigations. One year later, the community cautiously moves forth.The story of Abdisalam Yusuf

Public’s questions leave bitter taste for Seattle’s small Somalian community |

|

|

By Florangela Davila Seattle Times staff reporter Your typical Somali, explains Abdisalam Yusuf, talks about politics, how to raise money for a new mosque and community center, even the NBA. Cab drivers discuss — what else? — fares. And Yusuf and friends chat about the Mariners. Yusuf, a typical Somali by all accounts, is 28, slim, with a ribbon of a beard. He is dressed in a crisp purple shirt and gray slacks. He sells used cars. From his dealership in Seattle's Rainier Valley, Yusuf doesn't deflect Sept. 11 questions as much as he promotes conversation about the prosaic lives of Somalis, most of whom are Muslim. It hasn't always been easy, say local Somalis, to convince the public of their ordinariness. It hasn't always been easy, they say, when their community attracted so much attention only after things turned bad. The terrorist attacks triggered an avalanche of media reports about Islam and U.S. Muslims as the nation desperately sought to comprehend the unprecedented assault. Local Muslims — Arab and black, American or immigrant — can recall news stories that made them squirm because, they say, it unfairly lumped the Muslim extremists with regular folk. "All Christians in the U.S. aren't blamed for Ireland," says Yusuf, leaning on a '98 Nissan Sentra one recent evening. "Why are Muslims generalized as one group?" But what disturbed local Somalis even more was a pair of government investigations. First, federal authorities zeroed in on a bustling Somalian commercial nook, raiding three Seattle businesses as part of an international investigation of terrorism financing. Then officials prohibited three Seattle grocers from accepting food stamps, alleging food-stamp fraud. Then the reporters swarmed in. "Before, we just live, make money, work," says Omar Nur, in a blue apron, grinding halal meat at a local market. "After 9/11, every media gave us attention." Neither event resulted in the prosecution of any local person. In fact, groups like the American Civil Liberties Union and Seattle's Hate-Free Zone immediately rallied to the community's defense. Ten months after the Department of Treasury raid, two of the three businesses are open again. Two of the three grocers are again accepting food stamps after the Department of Agriculture, concluding "suspicious" shopping patterns actually just reflected cultural practices, reversed its ban. But in the Somalian community, the sting remains, and people are apprehensive, turning down requests for interviews. "Can't you just take a picture of the business sign?" one grocer asks. "You never know what might happen," says another, declining an interview, "because anything attached to Sept. 11 will be taken as either something positive or something negative." Nationwide, federal officials have tallied some 380 incidents of threats or violence directed at Arabs, Muslims, Sikhs and South Asians since Sept. 11. That includes the case of Patrick Cunningham, 53, who pleaded guilty to a Sept. 13 attack at Seattle's Islamic Idriss Mosque. Cunningham drove 25 miles from his Snohomish home, attempted to set fire to two cars at the mosque and shot at worshippers. None were hit. Complaints of religious or ethnic discrimination have more than doubled since Sept. 11 compared with the previous year, according to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. As of mid-August, the agency had logged 655 complaints. Fifty-seven percent of U.S. Muslims, according to a recent poll conducted by the Council on American-Islamic Relations, said they had experienced bias or discrimination since Sept. 11. But three out of four Muslims, the poll concluded, also experienced kindness or public support. Local Somalis carry their own memories of the aftermath, good and bad. "The kids were cool," says Omar, 16. "They all know I'm Muslim." Nothing bad happened to him, but he remembers defending his younger sister from some girls taunting her about her scarf. "The first day," recalls Mohamud Yusuf, a local journalist and cab driver who is no relation to the car salesman, "I removed my (cab driver ID) picture. I didn't want people to think about my name." But "when people (later) read my name, they asked, 'Are you being treated well? Are you meeting any bad people?' " Normal life continued, Yusuf says. And if you look around, it still does. An estimated 15,000 Somalis live in the greater Seattle area, having arrived little more than one decade ago after warlords, civil war and anarchy pummeled their East African country. They are one of the city's newest refugee groups — less established than the Cambodians, more so than the Sudanese orphans, known as the Lost Boys of Sudan. Somalis are largely nomadic, Yusuf explains, used to always moving through the desert to wherever the rains fell. "Right now," says Yusuf, surrounded by second-hand Dodges and GMs, "this is where the rain has come." In recent months, a Somali airport worker and part-time college student opened a tailor shop. A limousine driver opened a gift shop. And a former farmer, warehouse worker, fisherman and forklift driver reinvented himself as a Muslim grocer. On Rainier Avenue, cab drivers and moms stream into the recently opened Hamarwayne market, with its treasure trove of basement shops — a tailor, a beauty salon, a gift store. "Just like Africa," a woman says. On South Warsaw Street, a pair of engineers and a Fort Lewis soldier arrive at Yusuf's lot to hang out on the office couch. "This is one way to socialize," one man explains. "We do not go to nightclubs. You won't find Somalis in Pioneer Square." A good Muslim, says the Koran, should not take advantage of someone else, be in debt or charge interest. So Yusuf, a naturalized U.S. citizen, prices his cars for a little more than what he paid for and sells them for zero interest with 50 percent down. Thus far, half the customers at the 2-month-old dealership have been Somalis. The other half, black Americans. It took him nearly one year to start his business, filing paperwork, borrowing (interest-free) from family and friends, finding a lot next to Johnson's Auto Detail and just behind Smitty's Used Cars. "I think that's what America is all about," he says. "Competition." His only other sales experience was as a cashier at a Texaco station in Georgetown, after arriving in the U.S. in 1993. A guy strolled in and asked for a can of Copenhagen. Bewildered, Yusuf replied, You mean the capital? Is he any good at selling cars? "I don't know yet," says Yusuf, a reply that suggests he ought to be trusted. His dealership is called 101 Auto Sales, a wink to Yusuf's first U.S. college course, English 101. He whispers that he really hated the class. Florangela Davila: 206-464-2916 or fdavila@seattletimes.com. |

|

||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home |

| Home delivery | Contact us | Search archive | Site index |