|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

December 3, 1996

How favored few got best part of HUD pie

He owns two late-model cars and an almost-new pickup truck. He says he makes $35,000 a year, plus as much as $10,000 from a business property. He lives by himself in a five-bedroom adobe house — a house built with federal money earmarked for poor Native Americans. The money is from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and administered through the Northern Pueblos Housing Authority, an umbrella agency for the Pojoaque and five other area tribes. Jimmy Viarrial is the housing authority's chairman. And it seems that what the chairman wants, the chairman gets.

In 1993, when the authority received more than $1 million from

HUD to remodel and repair subsidized houses, whose house was at the

top of the list?

The agency spent $45,000 on it, installing a new roof and new kitchen appliances and adding a new water heater, furnace and wood-burning stove. The amount represented 5 percent of the total spent from the grant for remodeling houses for all the authority's six tribes. And all for a man whose salary was almost twice the $19,600 average income of New Mexico residents. Anna Padilla, a single mother who earns $15,000 a year, lives next door to Viarrial, in a much smaller HUD-subsidized house. When she asked for the same $4,000 cabinets that had been installed in

her neighbor's kitchen, housing-authority officials said no. In

fact, they said, if she wanted new cabinets, she'd have to buy them

herself.

Favoritism and inequity are not at all unusual in the disbursal of HUD money for Indian housing, The Seattle Times has found. Powerful tribal members routinely help themselves, their families and their friends to a disproportionate share of the HUD pie. "When someone gets into politics — let's say on a housing board or tribal council — it's almost an unwritten rule that you place those people who are your family and friends first. That's how it works," said Virginia Toews, a retired Indian-housing lobbyist living in Billings, Mont. "It's a wonderful way of doing business, unless you don't belong to the right families. Then you're excluded." HUD has done little to address this problem, mostly because of a decision four years ago to reduce regulation and oversight of the Indian-housing program.

Though deregulation had an honorable intent — to leave

important decisions to the tribes — in case after case examined by

The Times in a six-month investigation, tribal officials have taken

HUD money intended for the neediest Indians and instead used it for

their own gain.

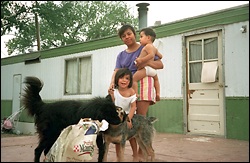

Even Viarrial's sister, who says she hasn't accepted special treatment, bemoans the greed displayed by her brother and others. "I feel like crying sometimes about the selfishness," Cordi Gomez said. "Too much taking advantage." The Pojoaque (poe-WA-key) reservation sits nearly 8,000 feet above sea level, on a dry, brushy plateau in northern New Mexico. Pojoaque and nearby pueblos are among the oldest towns in North America. That life could persist here for hundreds of years is remarkable, for the harsh landscape gives up little to the people. During the Depression, everyone moved away from the Pojoaque reservation, and the federal government nearly gave the land to a neighboring tribe. At the last minute, tribal emigres returned to save their sacred soil. They survived the first summer by eating green apricots. 'Mutual Help' designed to help poor HUD began building adobe houses here in the early 1960s. Viarrial and other tribe members obtained theirs under a HUD program known as Mutual Help, designed to help Native Americans buy houses on reservation land where banks were unwilling to finance home loans. Under Mutual Help, residents make lease payments to HUD for 15 to 25 years, paying an amount far less than the house is worth. Then, they get ownership. As with other tribes, there aren't enough subsidized houses to meet the need. Beverly Fierro, a 22-year-old Pojoaque resident, hoped to get a HUD house several years ago. She and her husband and child were squeezed into a one-bedroom house trailer, paying half their income for rent. She was told by a housing-authority official that she was second-highest on the priority list. But as a house became available, tribal officials told Fierro she was no longer on the list — even though she had since had a second child. The house was given instead to Viarrial's daughter. Mutual Help homebuyers pay no more than 15 percent of their monthly income toward house payments. They're expected to use some of their remaining money to keep the houses in good repair. As years went by, though, HUD officials found that many couldn't or didn't do needed maintenance, and the houses deteriorated. So in 1991, HUD started giving tribes grants for remodeling and repair. That money — nearly $150 million this year — has been an especially tempting target for practitioners of tribal favoritism. The money wasn't intended to go to tribal members such as Viarrial, who make enough to take care of their homes. But on the Pojoaque reservation and others — among them, the Chehalis in Washington state — it has paid for luxuries for the well-connected. David Perez, executive director of the Northern Pueblos Housing Authority, defends the work done on Viarrial's house. He said it was remodeled first as a test case to see how much it would cost to work on other people's houses. He couldn't recall what workmen had learned from the experiment, however, and conceded Viarrial got amenities others did not. Perez and Viarrial dismiss grievances about favoritism as tribal infighting. "I don't get involved in that," said Perez. "That stuff is not a priority for me." Viarrial said of the critics: "They always have something to complain about." In this case at least, the complaints are legitimate, says Tony Arroyos, a consultant who examined the books of the Northern Pueblos Housing Authority. An ex-Marine, Arroyos formerly worked as a housing specialist for the U.S. Senate. In the six years he has been a consultant, Arroyos has advised a score of housing authorities. Perez hired him in 1994 to consult on the Pojoaque home-remodeling project. Immediately, Arroyos saw things that alarmed him. He wondered about the extensive, expensive work being done on Chairman Viarrial's home. And when he looked at the housing authority's books, he "found all kinds of funny things going on." He was particularly concerned hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of repair work was going to two local, non-Indian contractors - Fred Tixier and Leroy Lopez - without standard competitive bidding and without attention to HUD's mandate that preference be given to Indian-owned contracting firms. Arroyos discovered that Tixier and Perez were longtime friends, as were Lopez and Viarrial. He found that the housing authority had hired the contractors on a house-by-house basis, rather than bundling the jobs into one large project as is traditionally done. Each contract was under $100,000, allowing the housing authority to avoid formal bidding. The only requirement was that the authority phone two other potential bidders in an effort to get a fair price. When Arroyos checked, he found that the authority had not bothered to keep a record of calls to other bidders, as required. Staffers told Arroyos that in most cases, no one else had been contacted. Arroyos also found that Perez had frequently paid Tixier upfront for work in progress, a violation of federal law and a potential problem because there was no guarantee the work would be completed properly. Normally, an inspector certifies that work has been done correctly before a contractor is paid. Arroyos said Tixier did not complete some work, and other work was substandard. The housing-authority inspector had been pressured to approve the poor work, Arroyos alleged. Perez acknowledged there were problems with Tixier's work, as did inspector Kenneth Peters. And Peters didn't deny he had been pressured to approve the work. "Everyone (at the housing authority) knows what is going on," said Leonel Chavez, 31, former fiscal director for the housing authority's remodeling program. "A lot of them are scared for their jobs." Chavez said Perez repeatedly ordered her to pay Tixier thousands of dollars before he even had contracts to do work. When she protested to Perez that he was violating the law, she was told to mind her own business, she said. Chavez resigned in August 1995. Perez said he forced her to resign because she had misfiled documents, including some he claims would have shown he had obtained other bids before hiring Tixier and Lopez. "I knew one day he would blame me," said Chavez. Failure to follow up In 1995, Arroyos took the Pojoaque case to HUD officials in Albuquerque: "I told HUD it is a garbage can over there." HUD facilities-management specialist Kim Forrester was sent to the Northern Pueblos to check out Arroyos' allegations. Perez was given a month's notice of the inspection, as required by HUD procedures, so he had plenty of opportunity to get records in order. Still, Forrester found plenty to corroborate Arroyos' story. Forrester's findings were detailed in a Feb. 26 letter to Perez from Frank Padilla, then director of HUD's Indian-program office in Albuquerque. Padilla told Perez to make corrections and politely praised the housing-authority staff for its cooperation. HUD staff members would make a follow-up visit in May to see that the authority had complied, the letter said. But that never happened. The office ran out of travel money, Forrester said. Besides, he said, "We are not in the business of telling them (the tribes) how to do their work." Ironically, that's what the tribe wanted. In July, concerned members of the Northern Pueblos Housing Authority board called for a full investigation of their agency by the HUD inspector general. They were concerned about the problems raised by Arroyos, and more. Two board members, speaking on condition of anonymity, said housing-authority tenants favored by management were wrongly paying 15 percent of net income, after taxes, for their houses rather than 15 percent of pre-tax, gross income. HUD could have discovered that by examining records, but officials at the regional office in Phoenix acknowledged they had not done an audit of the tenant payments for at least four years. Despite the alarms raised by Arroyos and others, though, HUD did nothing. Arroyos says when he asked Padilla why, he was told: "Tony, you know how this thing works. If I turned it in to the 'uppers,' they are not going to do anything about it. For right now, it is going to stay right here." Padilla said he didn't recall what he had told Arroyos, but said, "What you had at the Northern Pueblos is not anything different than what you get at other housing authorities." Padilla, who is now working in a different capacity with HUD, said he did not give the case to the inspector general because "the I.G. is just so inundated with this kind of stuff." Records not released Back at the Pojoaque pueblo in August, Perez told dissident members of his own housing board that if they continued to call for an investigation, their personal histories would be examined as well. When The Times asked Perez for particular records, he promised to release them but then changed his mind, saying he would welcome a federal investigation. The Times then filed an official request for the information with HUD Deputy Assistant Secretary Dominic Nessi, who oversees the Indian-housing program. When Nessi himself tried to get the records from Perez, he, too, was refused. "We are having a real problem with them," said Nessi. Perez said he will not release the records — which would show whose houses were remodeled and which contractors were contacted for competitive bids — until HUD asks for them as part of an investigation. Meanwhile, Arroyos said he has been told by insiders that housing-authority employees had been asked to look up contractors' names in the Yellow Pages and to write up phony bid records. Perez said he knows nothing about that, and said he had found old bid records scattered in his files. Not surprisingly, Arroyos no longer works as a consultant for the Northern Pueblos Housing Authority. "I thought he was a friend," said Viarrial. "He actually betrayed us."

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company