|

|

|

| Your account | Today's news index | Weather | Traffic | Movies | Restaurants | Today's events | ||||||||

|

December 1, 1996

Leaders replace needy on waiting list for homes

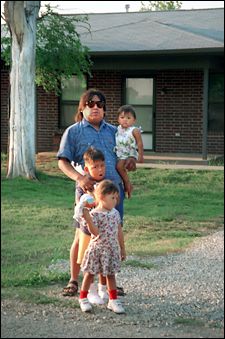

It's the key to a house he was promised under a federal program for Native Americans, a brand-new brick ranch house in the center of this village, home to the Otoe-Missouria Indians. With financing from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development — financing they couldn't get from traditional sources - Warrior and his wife would finally be able to afford their own home. Last January, the couple stood smiling in the middle of the empty living room, listening to the echo of excited voices as their children explored the bedrooms where they would soon be sleeping. But days before the move-in date, the family's plans were dashed: The house would no longer be theirs, they were told. All over town, other Otoe families on the waiting list for 20 HUD-financed houses got the same bad news. Leaders of the tribal-housing authority had created a new list - with themselves and their relatives and friends at the top.

Then they eliminated a requirement that recipients of the

houses had to pay for them — in effect, giving themselves free

houses.

"I actually had the key. We were thinking this was home," said Warrior. "We'd already planned where we'd put our furniture. Then it was all taken away. "What they did to me and my family was wrong." Loophole in new rules "What they did" was to take advantage of a new loophole in federal regulations, a loophole brought to the housing authority's attention by a former HUD official. The new rules, written in 1995, give tribal-housing authorities unrestricted power to set the prices of HUD-subsidized homes. But rather than using that power to establish a sliding scale of house payments to benefit their most needy members, leaders of the Otoe and other tribal-housing authorities instead used it to set themselves up in new houses at taxpayers' expense. The Otoes gave the houses away in exchange for what they called "sweat equity" — which amounted to nothing more than a commitment by the new homeowners to do their own post-construction cleanup work. Of the 20 houses given away in Red Rock: Five went to households that weren't low-income. At least as many went to tribal members who had no minor children living with them, even though families are supposed to get priority treatment. And two went to people who already had decent homes, although others on the waiting list didn't. All five board members got houses for themselves or family members. The board chairman and the housing-authority administrator, neither of whom has minor children, built themselves three-bedroom houses bigger than any others in the project. The actions destroyed whatever harmony this tribe had, pitting neighbor against neighbor. The Warriors and other jilted families cried foul to HUD, but to no avail. One family filed suit to recover its promised home, and eight others have met with an attorney to explore legal options. "I didn't ask for a free house," said Warrior, who makes minimum wage as a school-maintenance worker. "I was willing to pay for it." The Otoes' action, which has been duplicated by tribes in California, Arizona and Washington, not only lays waste to the dreams of families such as the Warriors, but threatens the existence of individual housing authorities. Revenues recouped from homeowners are supposed to help keep the housing authority afloat. When housing authorities give away homes for little or nothing, they essentially give away their future, and that of tens of thousands of Indians languishing on their waiting lists. From HUD job to consultant The Otoes were led to the loophole by Jim Cook, who went to work for the tribe's housing authority as a paid consultant two days after he retired from HUD. The housing authority gave him a two-year, $107,000 contract. Cook confirms he showed the board members the loophole and explained how they could leapfrog others on the waiting list. He also showed them how to get around a rule against giving HUD houses to people who already own homes. "I'm working for a different master now," he said without hesitation. "It is amazing what you can find when you read the regulations." Cook's employment by the Otoes reflects one reason HUD's Indian-housing program is such a mess: HUD employees crossing over to help tribes get around the intent of federal laws. Cook spent 30 years at HUD, ascending to the No. 2 position in the Oklahoma City regional office of the Indian program before retiring on Dec. 31. On Jan. 2, he went to work for the Otoes. But long before that, he was developing a tight relationship with the tribe: He took on oversight of the housing authority, co-signed its checks, listed the Otoe address as his own in correspondence and gave himself security clearance to draw money from the tribe's grant account in the federal treasury. In his last four months at HUD, 23 of the 24 business trips Cook took were to Red Rock, although it was just one of 30 housing authorities for which he was responsible. He decided the Otoes needed a consultant, wrote up the bid specifications for the job and then won the contract when he retired. Cook insists he didn't pursue the Otoe contract until his departure from HUD — even though New Year's Day was the only day between jobs. 'What we thought was best' Red Rock is a small grid of gravel streets lined with run-down houses and a cafe — a pocket-size community along a two-lane road that connects the county seat at Perry with the Conoco plant in Ponca City. About 300 Otoe-Missouria Indians live here, out of a total tribal enrollment of 1,600. Many others live nearby, descendants of seven clans who settled the northeast corner of Oklahoma 115 years ago after harsh winters and white settlers drove them from Nebraska. Farmland stretches in every direction as far as the eye can see, the terrain as flat and featureless as a table top. The red dirt yields wheat and corn — but not for the Otoes, who were hunter-gatherers, not farmers. They had neither the inclination nor know-how to raise crops. Their primary source of income has been the Otoe bingo hall, built in the mid-1980s with great expectations it has yet to fulfill. The hall has been closed most of the year for lack of an operator. "We don't really have any resources other than the land base," said tribal chairman Raymond Butler. "I guess we had some oil once, but not anymore." As a result, many of the houses in Red Rock were built with HUD money and rented or sold over time to their occupants, who pay the housing authority a percentage of their monthly income. "How do you think they feel when they hear houses are being given away?" said Butler, who has no control over the housing authority, an autonomous agency. The officials who carried out the giveaway have not felt the need to appease Red Rock's angry residents nor to offer any explanation for their actions. "We did what we thought was best for the people," said Claude Dailey, who recently stepped down as housing-authority chairman. That's all he would say. 'It looks pretty bleak' After Warrior was bumped from the housing list, he and his two sisters — who also had been bumped — drove 70 miles south to the HUD office in Oklahoma City. They met with Regional Administrator Wayne Sims and his assistant. Sims took no notes, made no copies of the family's carefully kept files and, in the end, declined to take action. "After talking to them, I just gave up," Warrior said. "We told them everything that was happening: who was removed from the list, the executive director and chairman getting houses. They said there was nothing they could do. It was up to the housing authority and the tribe." Sims explained HUD's inaction this way: "Since I've been here, there's always been a philosophy that these sorts of things should be handled locally. This is a program that offers tribes more autonomy." HUD did nothing for four more months, when escalating complaints from angry tribal members finally provoked a visit. It took HUD staff barely half a day at the Otoe housing-authority office to uncover enough evidence of impropriety to demand an accounting for the changes in the waiting list, and to halt any further changes. But by then, all but eight of the 20 houses had been transferred. It's probably too late to make things right for those who lost out. "On the surface, it looks pretty bleak," said Jack McCarty, an attorney who has met with eight of the families who were bumped. "HUD let the housing authority have this money with no controls. The damage is pretty severe." Meanwhile, Warrior is renting a tiny cottage in Ponca City. It's a tight fit for three active children, but at least it's a roof over their heads. "I did everything I was supposed to," he said. "In the end, it didn't matter." They visit friends and family in Red Rock, but his wife won't go near the street where their dream house is occupied by someone else. The taste of disappointment is still too bitter. "The kids were asking a month or two later, 'When are we going to move into the house?' " Warrior said. "What am I supposed to tell them?"

Copyright © 1996 Seattle Times Company, All Rights Reserved.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

seattletimes.com home

Home delivery

| Contact us

| Search archive

| Site map

| Low-graphic

NWclassifieds

| NWsource

| Advertising info

| The Seattle Times Company